The Bridge (10 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

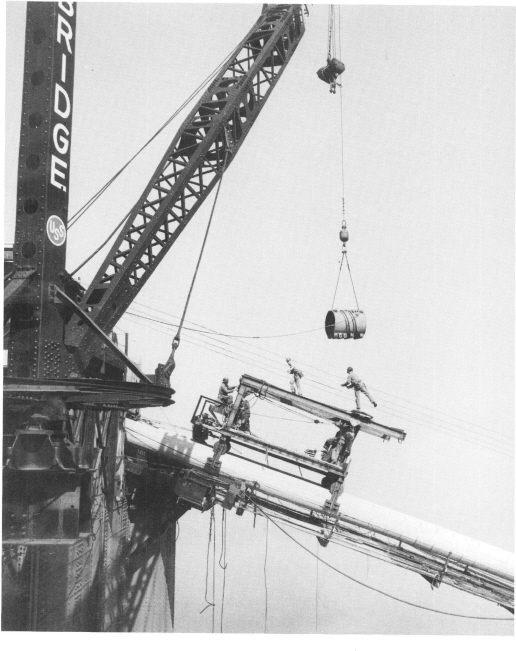

Suddenly all the men's attention, and also the binoculars along the shore, were focused on Kelly as he carefully watched a

dozen ironworkers link the heavy hoisting ropes to the four upper extremities of the steel piece as it gently rocked with

the anchored barge. When the ropes had been securely bcund, the men jumped off the barge onto another barge, and so did Kelly,

and then he called out, "Okay, ease now . . . up . . . UP . . ."

Slowly the hauling machines on the tower, their steel thread strung up through the cables and then down all the way to the

four edges of the steel unit on the sea, began to grind and grip and finally lift the four hundred tons off the barge.

Within a few minutes, the piece was twenty feet above the barge, and Kelly was yelling, "Slack down . . ." Then, "Go ahead

on seven," "Level it up," "Go ahead on seven"; and up on the bridge the signal man, phones clamped to his ears, was relaying

the instructions to the men inside the hauling vehicles. Within twenty-five minutes, the unit had climbed 225 feet in the

air, and the connectors on top were reaching out for it, grabbing it with their gloves, then linking it temporarily to one

of the units already locked in place.

"Artfully done," said one of the old men with binoculars. "Yes, good show," said another.

Most of the sixty pieces went up like this one—with remarkable efficiency and speed, despite the wind and bitter cold, but

just after New Year's Day, a unit scheduled to be lifted onto the Brooklyn backspan, close to the shoreline, caused trouble,

and the "seaside superintendents" had a good view of Murphy's temper.

As the steel piece was lifted a few feet off the barge, a set of hold-back lines that stretched horizontally from the Brooklyn

tower to the rising steel unit broke loose with a screech. (The holdback lines were necessary in this case because the steel

unit had to rise at an oblique angle, the barge being unable to anchor close enough to the Brooklyn shoreline to permit the

unit a straight ride upward.)

Suddenly, the four-hundred-ton steel frame twisted, then went hurtling toward the Brooklyn shore, still hanging on ropes,

but out of control. It swished within a few inches of a guard-rail fence beneath the anchorage, then careened back and dangled

uneasily above the heads of a few dozen workmen. Some fell to the ground; others ran.

"Jes-sus," cried one of the spectators on shore. "Did you see that?"

"Oh, My!"

"Oh, if old man Ammann were here now, he'd have a fit!"

Down below, from the pier and along the pedestals of the tower, as well as up on the span itself, there were hysterical cries

and cursing and fist waving. A hurried telephone call to Hard Nose Murphy brought him blazing across the Narrows in a boat,

and his swearing echoed for a half-hour along the waterfront of Bay Ridge.

"Which gang put the clamps on that thing?" Murphy demanded.

"Drilling's gang," somebody said.

"And where the hell's Drilling?"

"Ain't here today."

Murphy was probably never angrier than he was on this particular Friday, January 5. John Drilling, who had led such a charmed

life back on the Mackinac Bridge in Michigan, and who had recently been promoted to pusher though he was barely twenty-seven

years old, had called in sick that day. He was at his apartment in Brooklyn with his blond wife, a lovely girl whom he'd met

while she was working as a waitress at a Brooklyn restaurant. His father, Drag-Up Drilling, had died of a heart attack before

the cable spinning had begun, and some people speculated that if he had lived he might have been the American Bridge superintendent

in place of Hard Nose Murphy. The loss of his father and the responsibility of a new wife and child had seemed to change John

Drilling from the hell-raiser he had been in Michigan to a mature young man. But now, suddenly, he was in real trouble. Though

he was not present at the time of the accident that could have caused a number of deaths, he was nevertheless responsible;

he should have checked the clamps Then they were put on by his gang the day before.

When John Drilling returned to the bridge, not vet aware of the incident, he was met. by his friend and fellow boomer. Ace

Cowan, a bis Keiituckian who was the walkin" boss along the Brooklyn back span.

"What you got lined out for today Ace?"" Drilling said cheerfully upon arrival in the* morning.

"Er, well," Cowan said, looking at his feet, "'they . . . the office* made me put you back in the gang."

"'The gang! what, for taking a lousy day off?"

"No, it was those clamps that slipped . . ."

Drilling's lace fell.

"Anybody hurt?"

"No," Cowan said, "but everybody is just pissed . . . I mean Ammann and Whitney, and Murphy, and Kelly, and everybody."

"Whose gang am I in?'"

"Whitey Miller's."

Whitey Miller, in the opinion of nearly

every

bridgeman who had ever worked within a mile" of him, was the toughest, mean est, pushiest pusher on the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge. I )rilling swallowed hard.

That night in Johnny's Bar near the bridge, the men spoke about little else.

"Hear about Drilling?"

"Yeah, poor guy."

"They put him in Whitey Miller's gang."

"It's a shame."

"That Whitey Miller's a great ironworker, though," one cut in. "You gotta admit that."

"Yeah, I admit it, but he don't give a crap if you get killed."

"I wouldn't say that."

"Well, I would. I mean, he won't even go to your goddam funeral, that Whitey Miller."

But in another bar in Brooklyn that night, a bar also filled with ironworkers, there was no gloom—no worries about Whitey

Miller, no anguish over Drilling. This bar, The Wigwam, at 75 Nevins Street in the North Gowanus section, was a few miles

away from Johnny's. The Wigwam was where the Indians always drank. They seemed the most casual, the most detached of ironworkers;

they worked as hard as anybody on the bridge, but once the workday was done they left the bridge behind, forgot all about

it, lost it in the cloud of smoke, the bubbles of beer, the jukebox jive of The Wigwam.

This was their home away from home. It was a mail drop, a club. On weekends the Indians drove four hundred miles up to Canada

to visit their wives and children on the Caughnawaga reservation, eight miles from Montreal on the south shore of the St.

Lawrence River; on weeknights they all gathered in The Wigwam drinking Canadian beer (sometimes as many as twenty bottles

apiece) and getting drunk together, and lonely.

On the walls of the bar were painted murals of Indian chiefs, and there also was a big photograph of the Indian athlete Jim

Thorpe. Above the entrance to the bar hung a sign reading: THE GREATEST IRON WORKERS IN THE WORLD PASS THRU THESE DOORS.

The bar was run by Irene and Manuel Vilis—Irene being a friendly, well-built Indian girl born into an ironworkers' family

on the Caughnawaga reservation; Manuel, her husband, was a Spanish card shark with a thin upturned mustache; he resembled

Salvadore Dali. He was born in Galicia, and after several years in the merchant marine, he jumped ship and settled in New

York, working as a busboy and bottle washer in some highly unrecommended restaurants.

During World War II he joined the United States Army, landed at Normandy, and made a lot of money playing cards. He saved

a few thousand dollars this way, and, upon his discharge, and after a few years as a bartender in Brooklyn, he bought his

own saloon, married Irene, and called his place The Wigwam. More than seven hundred Indians lived within ten blocks of The

Wigwam, nearly every one of them ironworkers. Their fathers and grandfathers also were ironworkers. It all started on the

Caughnawaga reservation in 1886, when the Dominion Bridge Company began constructing a cantilever bridge across the St. Lawrence

River. The bridge was to be built for the Canadian Pacific Railroad, and part of the construction was to be on Indian property.

In order to get permission to trespass, the railroad company made a deal with the chiefs to employ Indian labor wherever possible.

Prior to this, the Caughnawagas—a tribe of mixed-blood Mohawks who had always rejected Jesuit efforts to turn them into farmers—earned

their living as canoemen for French fur traders, as raft riders for timber-men, as traveling circus performers, anything that

would keep them outdoors and on the move, and that would offer a little excitement.

When the bridge company arrived, it employed Indian men to help the ironworkers on the ground, to carry buckets of bolts here

and there, but not to risk their lives on the bridge. Yet when the ironworkers were not watching, the Indians would go walking

casually across the narrow beams as if they had been doing it all their lives; at high altitudes the Indians seemed, according

to one official, to be "as agile as goats." They also were eager to learn the bridge business—it offered good pay, lots of

travel—and within a year or two, several of them became riveters and connectors. Within the next twenty years dozens of Caughnawagas

were working on bridges all over Canada.

In 1907, on August 29, during the erection of the Quebec Bridge over the St. Lawrence River, the span collapsed. Eighty-six

workmen, many Caughnawagas, fell, and seventy-five ironworkers died. (Among the engineers who investigated the collapse, and

coneluded that the designers were insufficiently informed about the stress capability of such large bridges, was O. H. Ammann,

then twenty-seven years old.)

The Quebec Bridge disaster, it was assumed, would certainly keep the Indians out of the business in the future. But it did

just the opposite. The disaster gave status to the bridgeman's job— accentuated the derring-do that Indians previously had

not thought much about—and consequently more Indians became attracted to bridges than ever before.

During the bridge and skyscraper boom in the New York metropolitan area in the twenties and thirties, Indians came down to

New York in great numbers, and they worked, among other places, on the Empire State Building, the R.C.A. Building, the George

Washington Bridge, Pulaski Skyway, the Waldorf-Astoria, Triborough Bridge, Bayonne Bridge, and Henry Hudson Bridge. There

was so much work in the New York City area that Indians began renting apartments or furnished rooms in the North Gowanus section

of Brooklyn, a centralized spot from which to spring in any direction.

And now, in The Wigwam bar on this Friday night, pay night, these grandsons of Indians who died in 1907 on the Quebec Bridge,

these sons of Indians who worked on the George Washington Bridge and Empire State, these men who were now working on the biggest

bridge of all, were not thinking much about bridges or disasters; they were thinking mostly about home, and were drinking

Canadian beer, and listening to the music.

"Oh, these Indians are crazy people," Manuel Vilis was saying, as he sat in a corner and shook his head at the crowded bar.

"All they do when they're away from the reservation is build bridges and drink."

"Indians don't drink any more than other ironworkers, Manny," said Irene sharply, defending the Indians, as always, against

her husband's criticism.

"The hell they don't," he said. "And in about a half-hour from now, half these guys in here will be loaded, and then they'll

get in their cars and drive all the way up to Canada."

They did this every Friday night, he said, and when they arrived on the reservation, at 2 A.M., they all would honk their

horns, waking everybody up, and soon the lights would be on in all the houses and everybody would be drinking and celebrating

all night— the hunters were home, and they had brought back the meat.

Then on Sunday night, Manuel Vilis said, they all would start back to New York, speeding all the way, and many more Indians

would die from automobile accidents along the road than would ever trip off a bridge. As he spoke, the Indians continued to

drink, and there were ten-dollar and twenty-dollar bills all over the bar. Then, at 6:30 P.M., one Indian yelled to another,

"Com'on, Danny, drink up, let's move." So Danny Montour, who was about to drive himself and two other Indians up to the reservation

that night, tossed down his drink, waved goodbye to Irene and Manuel, and prepared for the four-hundred-mile journey.

Montour was a very handsome young man of twenty-six. He had blue eyes, sharp, very un-Indian facial features, almost blond

hair. He was married to an extraordinary Indian beauty and had a two-year-old son, and each weekend Danny Montour drove up

to the reservation to visit them. He had named his young son after his father, Mark, an ironworker who had crippled himself

severely in an automobile accident and had died not long afterward. Danny's paternal grandfather had fallen with the Quebec

Bridge in 1907, dying as a result of injuries. His maternal grandfather, also an ironworker, was drunk on the day of the Quebec

disaster and, therefore, in no condition to climb the bridge. He later died in an automobile accident.

Despite all this, Danny Montour, as a boy growing up, never doubted that he would become an ironworker. What else would bring

such money and position on the reservation? To not become an ironworker was to become a farmer—and to be awakened at 2 A.M.

by the automobile horns of returning ironworkers.

So, of the two thousand men on the reservation, few became farmers or clerks or gas pumpers, and fewer became doctors or lawyers,

but 1,700 became ironworkers. They could not escape it. It got them when they were babies awakened in their cribs by the horns.

The lights would go on, and their mothers would pick them up and bring them downstairs to their fathers, all smiling and full

of money and smelling of whiskey or beer, and so happy to be home. They were incapable of enforcing discipline, only capable

of handing dollar bills around for the children to play with, and all Indian children grew up with money in their hands. They

liked the feel of it, later wanted more of it, fast—for fast cars, fast living, fast trips back and forth between long weekends

and endless bridges.

"It's a good life," Danny Montour was trying to explain, driving his car up the Henry Hudson Parkway in New York, past the

George Washington Bridge. "You can see the job, can see it shape up from a hole in the ground to a tall building or a big

bridge."

He paused for a moment, then, looking through the side window at the New York skyline, he said, "You know, I have a name for

this town. I don't know if anybody said it before, but I call this town the City of Man-made Mountains. And we're all part

of it, and it gives you a good feeling—you're a kind of mountain builder . . ."

"That's right, Danny-boy old kid," said Del Stacey, the Indian ironworker who was a little drunk, and sat in the front seat

next to Montour with a half-case of beer and bag of ice under his feet. Stacey was a short, plump, copper-skinned young man

wearing a straw hat with a red feather in it; when he wanted to open a bottle of beer, he removed the cap with his teeth.

"Sometimes though," Montour continued, "I'd like to stay home more, and see more of my wife and kid . . ."

"But we can't, Danny-boy," Stacey cut in, cheerfully. "We gotta build them mountains, Danny-boy, and let them women stay home

alone, so they'll miss us and won't get a big head, right?" Stacey finished his bottle of beer, then opened a second one with

his teeth. The third Indian, in the back seat, was quietly sleeping, having passed out.

Once Montour had gotten the car on the New York Thruway, he began to speed, and occasionally the speedometer would tip between

ninety and one hundred miles per hour. He had had three or four drinks at The Wigwam, and now, in his right hand, he was sipping

a gin that Stacey had handed him; but he seemed sober and alert, and the expressway was empty, and every few moments his eyes

would peer into the rear-view mirror to make certain no police car was following.

Only once during the long trip did Montour stop; in Maiden, New York, he stopped at a Hot Shoppe for ten minutes to get a

cup of coffee—and there he saw Mike Tarbell and several other Indians also bound for Canada. By 11 P.M. he was speeding past

Warrensburg, New York, and an hour or so later he had pulled off the expressway and was on Route 9, a two-lane backroad, and

Stacey was yelling, "Only forty miles more to go, Danny-boy."

Now, with no radar and no cars coming or going, Danny Montour's big Buick was blazing along at 120 miles per hour, swishing

past the tips of trees, skimming over the black road—and it seemed, at any second, that a big truck would surely appear in

the windshield, as trucks always appear, suddenly, in motion-picture films to demolish a few actors near the end of the script.

But, on this particular night, there were no trucks for Danny Montour.

At 1:35 A.M., he took a sharp turn onto a long dirt road, then sped past a large black bridge that was silhouetted in the

moonlight over the St. Lawrence Seaway—it was the Canadian railroad bridge that had been built in 1886, the one that got Indians

started as ironworkers. With a screech of his brakes, Montour stopped in front of a white house.

"We're home, you lucky Indians," he yelled. The Indian in the back seat who had been sleeping all this time woke up, blinked.

Then the lights went on in the white house; it was Montour's house, and everybody went in for a quick drink, and soon Danny's

wife, Lorraine, was downstairs, and so was the two-year-old boy, Mark. Outside, other horns were honking, other lights burned;

and they remained alive, some of them, until 4 A.M. Then, one by one, they went out, and the last of the Indians fell asleep—not

rising again until Saturday afternoon, when they would be awakened, probably, by the almost endless line of bill collectors

knocking on doors: milkmen, laundrymen, newsboys, plumbers, venders of vacuum cleaners, encyclopedia salesmen, junk dealers,

insurance salesmen. They all waited until Saturday afternoon, when the ironworker was home, relaxed and happy, to separate

him from his cash.

The reservation itself is quiet and peaceful. It consists of a two-lane tar road that curves for eight miles near the south

shore of the St. Lawrence River. Lined along both sides of the road and behind it are hundreds of small white frame houses,

most of them with porches in front—porches often occupied by old Indian men. They slump in rocking chairs, puffing pipes,

and quietly watch the cars pass or the big ships float slowly through the St. Lawrence Seaway—ships with sailors on deck who

wave at any Indian women they see walking along the road.

Many of the younger Indian women are very pretty. They buy their clothes in Montreal shops, have their hair done on Friday

afternoons. There is little about their style of clothing or about their homes that is peculiarly Indian—no papooses, no totems,

no Indian gadgets on walls. Some Indian homes do not have running water, and have outhouses in the back, but all seem to have

television sets. The only sounds heard on Saturday afternoon are the clanging bells of the Roman Catholic church along the

road—most Indians are Catholics—and occasionally the honking of an Indian motorcade celebrating a wedding or christening.