The Bridge (12 page)

Authors: Gay Talese

"Roy, remember that barking dog that used to scare hell out of us?"

"Yeah."

"And remember that candy store that used to be here?"

"Yeah, Harry's. We used to steal him blind"

"And remember"

"Hey," Roy said, "I wonder if Vera is still around?"

"Let's get to a phone booth and look her up."

They walked three blocks to the nearest sidewalk booth, and Roy looked up the name and then called out, "Hey, here it is—

SHore 5-8486."

He put in a dime, dialed the number, and waited, thinking how he would begin. But in another second he realized there was

no need to think any longer, because there was only a click, and then the coldly proper voice of a telephone operator began,

"I am sorry. The number you have reached is not in service at this time. . . . This is a recording."

Roy picked out the dime, put it in his pocket. Then he and his brother walked quietly to the corner, and began to wait for

the bus— but it never came. And so, without saying anything more, they began to walk back to their other home, the noisy one,

on Fifty-second Street. It was not a long walk back—just a mile and a half—and yet in 1959, when they were young teenagers,

and when it had taken the family sixteen hours to move all the furniture, the trip to the new house in a new neighborhood

had seemed such a voyage, such an adventure.

Now they could see, as they walked, that it had been merely a short trip that had changed nothing, for better or for worse—it

was as if they had never moved at all.

A disease common among ironworkers—an itchy sensation called "ramblin' fever"—seemed to vibrate through the long steel cables

of the bridge in the spring of 1964, causing a restlessness, an impatience, a tingling tension within the men, and many began

to wonder: "Where next?"

Suddenly, the bridge seemed finished. It was not finished, of course—eight months of work remained—but all the heavy steel

units were now linked across the sky, the most dangerous part was done, the challenge was dying, the pessimism and cold wind

of winter had, with spring, been swept away by a strange sense of surety that nothing could go wrong: a punk named Roberts

slipped off the bridge, fell toward the sea—and was caught in a net; a heavy drill was dropped and sailed down directly toward

the scalp of an Indian named Joe Tworivers—but it nipped only his toes, and he grunted and kept walking.

The sight of the sixty-four-hundred-ton units all hanging horizontally from the cables, forming a lovely rainbow of red steel

across the sea from Staten Island to Brooklyn, was inspiring to spectators along the shore, but to the ironworkers on the

bridge it was a sign that boredom was ahead. For the next phase of construction, referred to in the trade as "second-pass

steel," would consist primarily of recrossing the entire span while lifting and inserting small pieces of steel into the structure—struts,

grills, frills—and then tightening and retightening the bolts. When the whole span had been filled in with the finishing steel,

and when all the bolts had been retightened, the concrete mixers would move in to pave the roadway, and next would come the

electricians to string up the lights, and next the painters to cover the red steel with coats of silver.

And finally, when all was done, and months after the last ironworker had left the scene for a challenge elsewhere, the bridge

would be opened, bands would march across, ribbons would be cut, pretty girls would smile from floats, politicians would make

speeches, everyone would applaud—and the engineers would take all the bows.

And the ironworker would not give a damn. He will do his boasting in bars. And anyway, he will know what he has done, and

he would somehow not feel comfortable standing still on a bridge, wearing a coat and tie, showing sentimentality.

In fact, for a long time afterward he will probably not even think much about the bridge. But then, maybe four or five years

later, a sort of ramblin' fever in reverse will grip him. It might occur while he is driving to another job or driving off

to a vacation; but suddenly it will dawn on him that a hundred or so miles away stands one of his old boom towns and bridges.

He will stray from his course, and soon he will be back for a brief visit: Maybe it is St. Ignace, and he is gazing up at

the Mackinac Bridge; or perhaps it's San Francisco, and he is admiring the Golden Gate; or perhaps (some years from now) he

will be back in Brooklyn staring across the sea at the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

Today he will doubt the possibility, most of the boomers will, but by 1968 or 769 he probably will have done it: He may be

in his big car coming down from Long Island or up from Alanhattan, and he will be moving swiftly with all the other cars on

the Belt Parkway, but then, as they approach Bay Ridge, he will slow up a bit and hold his breath as he sees, stretching across

his windshield, the Verrazano—its span now busy and alive with auto traffic, bumper-to-bumper, and nobody standing on the

cables now but a few birds.

Then he will cut his car toward the right lane, pulling slowly off the Belt Parkway into the shoulder, kicking up dust, and

motorists in the cars behind will yell out the window, "Hey, you idiot, watch where you're driving," and a woman may nudge

her husband and say, "Look out, dear, the man in that car looks drunk."

In a way, she will be right. The boomer, for a few moments, will be under a hazy, heady influence as he takes it all in—the

sights and sounds of the bridge he remembers—hearing again the rattling and clanging and Hard Nose Murphy's angry voice; and

remembering, too, the cable-spinning and the lifting and Kelly saying, "Up on seven, easy now, easy"; and seeing again the

spot where Gerard McKee fell, and where the clamps slipped, and where the one-thousand-pound casting was dropped; and he will

know that on the bottom of the sea lies a treasury of rusty rivets and tools.

The boomer will watch silently for a few moments, sitting in his car, and then he will press the gas pedal and get back on

the road, joining the other cars, soon getting lost in the line, and nobody will ever know that the man in this big car one

day had knocked one thousand rivets into that bridge, or had helped lift four hundred tons of steel, or that his name is Tatum,

or Olson, or Iannielli, or Jacklets, or maybe Hard Nose Murphy himself.

Anyway, this is how, in the spring of 1964, Bob Anderson felt—he was a victim of ramblin' fever. He was itchy to leave the

Verrazano job in Brooklyn and get to Portugal, where he was going to work on a big new suspension span across the Tagus River.

"Oh, we're gonna have a ball in Portugal," Anderson was telling the other ironworkers on his last working day on the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge. "The country is absolutely beautiful, we'll have weekends in Paris . . . you guys gotta come over and join me."

"We will Bob, in about a month," one said.

"Yeah, Bob, I'll sure be there," said another. "This job is finished as far as I'm concerned, and I got to get the hell out.

. . ."

On Friday, June 19, Bob Anderson shook hands with dozens of men on the Verrazano and gave them his address in Portugal, and

that night many of them joined him for a farewell drink at the Tamaqua Bar in Brooklyn. There were about fifty ironworkers

there by 10 P.M. They gathered around four big tables in the back of the room, drank whiskey with beer chasers, and wished

Anderson well. Ace Cowan was there, and so was John Drilling (he had just been promoted back to pusher after three hard months

in Whitey Miller's gang), and so were several other boomers who had worked with Anderson on the Alackinac Bridge in Michigan

between 1955 and 1957.

Everyone was very cheerful that night. They toasted Anderson, slapping him on the back endlessly, and they cheered when he

promised them a big welcoming binge in Portugal. There were reminiscing and joke-telling, and they all remembered with joy

the incidents that had most infuriated Hard Nose Murphy, and they recalled, too, some of the merry moments they had shared

nearly a decade ago while working on the Alackinac. The party went on beyond midnight, and then, after a final farewell to

Anderson, one by one they staggered out.

Prior to leaving for Lisbon, Bob Anderson, with his wife, Rita, and their two children, packed the car and embarked on a brief

trip up to St. Ignace, Michigan. It was in St. Ignace, during the Alackinac Bridge job, that Bob Anderson had met Rita. She

still had parents and many friends there, and that was the reason for the trip—that and the fact that Bob Anderson wanted

to see again the big bridge upon which he had worked between 1955 and 1957.

A few days later he was standing alone on the shore of St. Ignace, gazing up at the Mackinac Bridge from which he had once

come bumping down along a cable, clinging to a disconnected piece of catwalk for 1,800 feet, and he remembered how he'd gotten

up after, and how everybody then had said he was the luckiest boomer on the bridge.

He remembered a great many other things, too, as he walked quietly at the river's edge. Then, ten minutes later, he slowly

walked back toward his car and drove to his mother-in-law's to join his wife, and later they went for a drink at the Nicolet

Hotel bar, which had been boomers' headquarters nine years ago and where he had won that thousand dollars shooting craps in

the men's room.

But now, at forty-two years of age, all this was behind him. He was very much in love with Rita, his third wife, and he had

finally settled down with her and their two young children. They both looked forward to the job in Portugal—and the possibility

of tragedy there never could have occurred to them.

In Portugal while looking for a house, the Andersons stayed at the Tivoli Hotel in Lisbon. Bob Anderson's first visit to the

Tagus River Bridge was on June 17. At that time the men were working on the towers, and the big derricks were hoisting up

fifty-ton steel sections that would fit into the towers. Anderson apparently was standing on the pier when, as one fiftyton

unit was four feet off the ground, the boom buckled and suddenly the snapped hoisting cable whipped against him with such

force that it sent him crashing against the pier, breaking his left shoulder and cracking open his skull, damaging his brain.

Nobody saw the accident, and the bridge company could only guess what had happened. Bob Anderson remained unconscious all

day and night and two months later he was still in a coma, unable to recognize Rita or to speak. Flis booming days were over,

the doctors said.

When word got back to the Verrazano in Brooklyn, it affected every man on the bridge. Some were too shocked to speak, others

swore angrily and bitterly. John Drilling and other boomers rushed off the bridge and called Rita in Portugal, volunteering

to fly over. But she assured them there was nothing they could do. Her mother had arrived from St. Ignace and was helping

care for the children.

For the boomers, it was a tragic ending to all the exciting time in New York on the world's longest suspension span. They

were proud of Bob Anderson. He had been a daring man on the bridge, and a charming man off it. His name would not be mentioned

at the Verrazano-Narrows dedication, they knew, because Anderson—and others like him—were known only within the small world

of the boomers. But in that world they were giants, they were heroes never lacking in courage or pride—men who remained always

true to the boomer's code: going wherever the big job was

. . .

and lingering only a little while

. . .

then off again to another town, another bridge .

. .

linking everything but their lives.

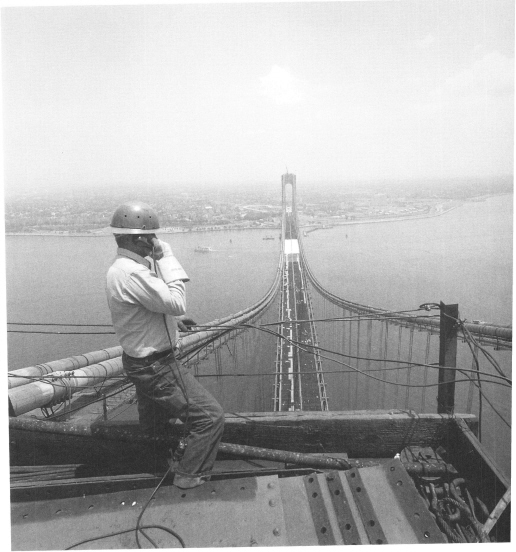

It is a sunny New York afternoon in the late summer, and I am standing near the western anchorage of the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge on the water's edge of Staten Island. I have come here to pose for the author's photograph of this book that is my

homage to the bridge that 1 first climbed forty years ago, when it spanned the harbor in a bridled state of juvenility without

purpose or responsibility, lacking at the time the concrete roadway, the directional signs, and the toll plaza that would

make it functional and self-supporting.

Now it has grown into a commercial colossus that is crossed every day by 250,000 vehicles that deposit a daily sum of one

million dollars, and it looms as the gateway to the city's harbor and to the high hopes that guide the entrepreneurial and

persevering in-trinsicality of New Yorkers. This day the bridge itself was receiving a facelift from crews of maintenance

workers who, moving up and down the towers and across the span in cable-suspended metal carts, were scraping rust spots off

the surface with wire brushes, and smearing reddish lead waterproofing paste over the steel before applying coats of light

gray paint with lamb's-wool rollers attached to long poles. The bridge is scraped and repainted from top to bottom every ten

years. It takes five years to complete the job, costing management about seventy-five million dollars.

The general manager of the bridge oversees its day-to-day operation from a brick office off the ramp near the Staten Island

anchorage. He is a mild-mannered man of fifty-two who stands six-feet four, weighs 250 pounds, and is named Robert Tozzi.

As a college student more than thirty years ago at St. John's University in Brooklyn, he worked for three summers as a toll

collector on the Verrazano, beginning in 1969, five years after it opened, when the fare for each passenger vehicle was $.50

(it is now a round-trip fare of $7.00 per passenger vehicle) and amounted to almost one thousand dollars in coins and currency

during each eight-hour work shift. As a toll collector Robert Tozzi was paid twenty dollars a day.

The booth he used to occupy is a short walk away from his present-day office. Hanging from his office walls are monitors showing

the flow of traffic across the bridge from thirty-two different camera angles—offering views from the two towers, the upper

and lower roadways, the anchorages, and other points—but nothing he sees varies much from what he saw the day before, or the

day before that. What happens on the bridge is quite predictable to him. Three vehicles will break down on the bridge almost

every day, briefly causing traffic jams. He expects, and usually gets, two auto crashes a day—fender benders or other collisions

not resulting in serious injuries. Traffic fatalities are rare, perhaps one every two years. The last one occurred in 1999.

Each year, on average, two individuals with suicidal tendencies select the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge as the jumping off point

to end their lives.

Robert Tozzi's father was a maintenance manager with the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which built many of the city's

toll-collecting facilities, including the Verrazano, and it was through his father's introduction that the younger Tozzi came

to the agency. After three summers in the tollbooth, he was hired full time in 1975 to drive one of the Verrazano's tow trucks,

helping to remove disabled cars from the roadway.

In 1974, when he was twenty-four, Tozzi was offered the opportunity to drive one of the agency's sedans in order to chauffeur

the Triborough's chairman, Robert Moses. For the next four-and-a-half years, dutifully and diplomatically, Tozzi drove Moses

to countless locations. He knew that Moses, deficient in grace even in the best of times, was embittered over the bad press

and negative commentary he had been receiving since the publication in 1974 of Robert Caro's highly critical book about him,

entitled

The Power Broker

and subtitled:

Bobert Moses and the Fall of New York.

Approaching the end of his long career as an urban planner—he had paved the way for the creation of the Verrazano-Narrows

Bridge and other great undertakings that he believed the public needed and should appreciate— Moses as an octogenarian found

himself being second-guessed and excoriated on talk shows and in the media for his past decisions to demolish vast areas of

living space and dispossess multitudes of people in order to build new highways, bridges, tunnels, and tollgates. In 1975

the Caro book won the Pulitzer Prize, adding insult to injury as far as Aloses was concerned.

On the day I met Robert Tozzi—he escorted me to the anchorage himself, a necessary courtesy attributable to security policies

instituted since the World Trade Center attacks—he said that he had never gotten around to buying

The Power Broker,

although the book is popular with many of his fellow employees.

Robert Moses is now long deceased, as is the Verrazano's chief designer, O. H. Ammann, and also many of the residents and

businesspeople of Brooklyn and Staten Island who in the late 1950s tried without success to prevent Moses from destroying

their neighborhoods that stood in the proposed pathways to the bridge. Some of them, however, recently told me that their

worst fears had failed to transpire, that the new location into which they had been forced to move their businesses or domiciles

turned out not to be as disruptive or depressing as they had imagined. The structures they had moved to were generally in

better condition than the ones they had surrendered to the wrecking crews; and while what they lost in sentimental value was

irredeemable, and while they continued to resent the arbitrary power that Moses had wielded over their lives, they gradually

became resigned to the inevitability of change and their inability to resist it.

Among those who spoke out in 1959 against Moses's plan for the bridge was a dentist, Henry Amen, whose office in the Bay Ridge

section of Brooklyn was designated to be leveled and paved over by the road builders. Dr. Amen was fortunate in finding a

new office convenient enough for his Bay Ridge—based practice; he is still there today, working at the age of seventy-six,

having as a partner a dentist of thirty-four who is his daughter.

Another anti-Moses spokesman who I interviewed in the late 1950s was Joseph V. Sessa, who had somberly predicted his firm's

demise after learning that the condemned properties in his neighborhood would result in the dispersal of 2,500 families "from

which to draw." This figure was more than a third of the estimated 7,000 people who were being dislodged; but the mortician,

unlike the dentist, would not see his own workplace destroyed. It was located along the fringe of the targeted area, on Fort

Hamilton Parkway, and it remains there as it was, still dedicated to burying people—including Mr. Sessa, who passed away in

1977 at the age of seventy-nine. His resourceful grandson, Joseph J. Sessa, now operates the family business and has expanded

it to include two other mortuaries located elsewhere in Brooklyn.

The family that was perhaps the most inconvenienced by the construction of the bridge's approachways was that of a Brooklyn

Navy Yard worker, John G Herbert, who, with his wife, Margaret, and fifteen of their seventeen children, resided until 1959

in a comfortable old ramshackle corner house on a hill adjacent to a park in the Bay Ridge area. Since their dwelling was

soon to be pulverized, Mr. and Mrs. Herbert were persistently encouraged by the Triborough's resettlement office to select

one of the three spacious houses that was available to them less than two miles away. Although they were unenthusiastic about

the houses they were shown—none was near a park, all were located on densely populated blocks—they settled for the one closest

to that which they were leaving. It took the couple twelve trips and eighteen hours to convey their children, their furniture,

and the rest of their possessions; and, other than the resentment expressed along the way by their fifteen-year-old boy, Eugene,

and his fourteen-year-old brother, Roy, the transfer was completed with efficiency.

After Eugene and Roy had been told to walk back to the old homestead to retrieve a pet cat that had been forgotten, they expressed

their feelings about the displacement by throwing bricks through what had been their bedroom windows, and with a rusty axe

they chopped down the wooden railings of the front porch and the bannisters of the interior staircase, and knocked holes into

the plaster walls—a cathartic experience.

More than forty years later, Eugene is fifty-eight and recently retired from his job installing Otis elevators. (His thirteen

surviving siblings now reside in various parts of New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Ohio, Minnesota, and Florida.) He lives

in a rented second-story Brooklyn apartment with his wife and their twenty-year-old daughter who works in a doctor's office.

The apartment is located on a busy residential block lined with row houses and trees and hard-to-find parking spaces. It is

in the Bay Ridge section, not far from where Eugene Herbert's parents last lived. Although he pays it little notice, the Brooklyn

tower of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge rises above the rooftops of his neighborhood.

In Staten Island the bridge is also no longer an object of great interest or angst. Here a new generation of settlers, having

grown up with it, accept it as essential to their expanding development, the highlight of their horizon, their link to the

mammoth mosaic that is Brooklyn and to the seafront towers of Lower Manhattan that the writer Truman Capote once described

as a "diamond iceberg."

Although the Staten Island population of 443,000 (in a city of over 8 million) is now nearly double that of the prebridge

figure, and while the island's once sprawling farmlands have disappeared along with the country roads through which motorists

once moved bumpily past herds of grazing cattle, a provincial atmosphere still prevails here. Along tree-shaded residential

streets one sees row upon row of single-family white frame houses with shuttered windows and roadside mailboxes and tidy lawns

with poles bearing American flags that were on display long before the recent nationwide proliferation of patriotism prompted

by the attacks of terrorists. These flags flew steadfastly in Staten Island as other flags were being burned in Manhattan

and elsewhere by college students and others among the anti—Vietnam War activists of the 1960s and early '70s.

Staten Islanders are traditionally conservative, standard-bearing advocates of law and order. A disproportionate number of

them serve the city as police officers and firefighters, and among the 343 New York City firefighters who lost their lives

in the World Trade Center disaster,

78

were from Staten Island. Residents of Irish ancestry have historically influenced the social and political landscape here,

but now their coreligionists, the Italian-Americans, are the dominant group. A majority of them are related ancestrally to

agrarian villages in Southern Italy, and they have reinforced a "village mentality" on the island, a sense of insularity and

regularity, an affinity for familiarity.

This is not to say that Staten Island is without its diversity of newcomers. Asians and Jews from Russia have joined such

tenured minorities as Hispanics and African-Americans. But the island remains a bastion of blue-collar white families and

cadres of middle-management commuters and young women who are employed in Manhattan as secretaries, bank tellers, and sales

reps and who, in many cases, will quit these jobs once they marry and have children.

Among the island's commuting population is a strapping, ruddy-complected man of six-feet-two named John McKee, who, after

placing his boots, his tool belt, and his hard hat in the trunk of his car, drives to work across the bridge that forty years

before he had helped to erect. His two bridge-building brothers were then with him on the job; and on a cloudy, windy Wednesday

morning in early October of 1963, eight months before the skeletal steel structure of the Verrazano was fully bracketed and

bolted, John McKee's younger brother, Gerard, slipped off one of the cables and fell more than 350 feet into the water, hitting

with such force that he immediately lost his life.

There was a work stoppage that day, and subsequently a five-day strike was initiated by the union boss of Local 40, Ray Corbett,

who, though fearless when he himself was a young man wearing a hard hat—in 1949 he stood casually atop the Empire State Building

overseeing the installation of its 224-foot television tower—believed in 1963, in the wake of Gerard McKee's death and two

earlier fatalities, that the Verrazano project was becoming unnecessarily perilous and that safety nets should immediately

be strung up under the bridge's framework. This was finally agreed to by the management, and Ray Corbett's concern was justified

in the months ahead as three other bridge workers lost their balance but not their lives thanks to the nets.

Among the lucky trio was Robert Walsh, a friend of the McKee family and currently Local 40's business manager. The workers'

headquarters building in Manhattan, on Park Avenue South between thirtieth and thirty-first Streets, is named in honor of

Ray Corbett, who died in 1992 at the age of seventy-seven.

The two surviving McKee brothers have continued to practice their hazardous craft without debilitating injuries since Gerard's

death, but both men are contemplating their retirement. John McKee is fifty-nine. His brother, James, living in Brooklyn,

is sixty. James McKee's wife, Nettie, who is an administrative secretary with the borough's school system, has remained in

social contact with the late Gerard McKee's onetime fiancee, Margaret Nucito, who now resides in Florida, but in the early

1960s lived across the street from the McKees in Brooklyn, in the working class Catholic neighborhood of Red Hook.

Margaret was then acknowledged to be the prettiest girl on the block, a petite Italian-American redhead who spent her days

as a file clerk with the phone company and came directly home after work. She became engaged to Gerard McKee when they were

nineteen, after he had dropped out of high school in his final year to enroll in an apprentice program that would in time

qualify him to join his older brothers in Local 40.