The Bridge of San Luis Rey (14 page)

Read The Bridge of San Luis Rey Online

Authors: Thornton Wilder

Tags: #Fiction, #Classics, #Literary, #General

“And on what subject?”

“It hardly matters. Don't you think that in the whole of the world's literature there are only seven or eight great subjects? By the time of Euripides they had all been dealt with already, and all one can do is to pick them up again. He took them from history, or from foreign tales. Have you ever studied the sources of Shakespeare? I believe that the only character he created himself was Ariel in

The Tempest

.” (I've never understood why certain critics should stand amazed at Shakespeare's erudition or find it extraordinary in an actor. After all, Shakespeare was not a “humble player”; he lived at court. All his erudition is to be found in the little books which were to his age what bookstall volumes are to ours.) “The Romans took their subjects from the Greeks, Molière from the Romans, Corneille from the Spaniards, Racine from Corneille and the Bible. . . . Ibsen seems to me the only dramatist who has really invented themes, and isn't that just his real greatness? No, there is nothing new that a writer can hope to bring except a certain way of looking at life. . . . In my own case, for instance, what I seek everywhere is the mask under which human beings conceal their unhappiness.”

“So you think that all human beings are unhappy?”

“In social life, yes, all of themâin varying degrees. . . . They are solitary, they are consumed with desires which they dare not satisfy; and they wouldn't be happy if they did satisfy them, because they are too civilized. No, a modern man cannot be happy; he is a conflict, whether he likes it or not.”

“Even those tanned, ruddy Englishmen with their boyish eyes?”

“Just like the rest. And the proof is that they have humour. Humour is a mask to hide unhappiness, and especially to hide the deep cynicism which life calls forth in all men. We're trying to bluff God. It is called polish. . . . Our young people in America, it seems to me, express that cynicism more honestly than most Europeans do. Freud has helped them a lot.”

“But also spoilt them a lot. . . . In Freud there is a sexual obsession which simply is not true of the majority of men. . . .”

“Possibly. . . . There, again, I answer âpossibly' just to please you. Sexual life is so important.”

The whole afternoon passed in pleasant conversation. He talked very well about music, especially about Bach. Then of the theatre.

“I saw

Le Misanthrope

in Paris the other day,” he said, “but I was disappointed in the acting. They made Célimène into a most unattractive coquette. . . . No. . . . The terrible thing about Célimène is that she was very nice.”

“I once thought of writing Célimène's diary,” I told him. “It would have shown that her âbetrayals' were often, in her own eyes, merely attempts to placate Alceste and make him happy.”

About five o'clock he rose. Unfortunately we shan't see him again. He is going for a walking-tour with Gene Tunney, the boxer.

“A strange companion.”

“Don't think that. I'm very fond of him.”

Â

Yale Collection of American Literature

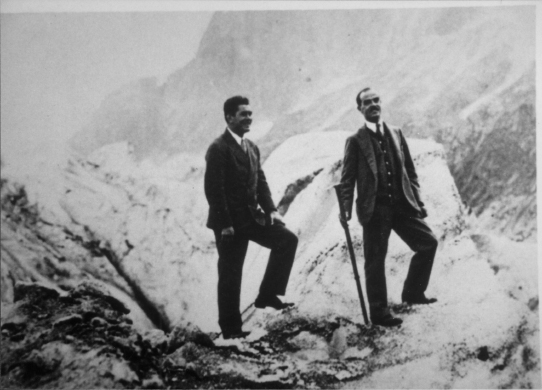

The Wilder biographer Gilbert Harrison describes the Wilder-Tunney walk in the Swiss Alps and southern France as “among the most publicized mini-events of the twenties.” It was never very strenuousâa sports car donated to the champ figures prominently in the story. They are seen here (Wilder with walking stick) on the edge of Mont Blanc in September 1928.

A Lecture

Mme. de Sévigné held a place in the forefront of Wilder's pantheon of literary heroes. The portrait he fashioned of her in the figure of the Marquesa de Montemayor in

The Bridge

is an often-noted feature of the novel. On May 3, 1928, Wilder delivered the Daniel S. Lamont Memorial Lecture at Yale on “English Letters and Letter Writers.” These excerpts focus on his subject and on his hero. The lecture, held at the Sampson Lyceum in New Haven, was open to town and gown and attracted an audience of several hundred. The lecture was retitled when published for the first time in 1979.

“On Reading the Great Letter Writers”

The very nature of letter writing is such that when we get together to discuss it there should never be more than a dozen persons. The great letter sequences are full of passages that you and I were never meant to see. I grant that some of the letters that I shall discuss were written with one eye on a larger audience; but many a letter by even the most conscious artists in this literature was not intended for the Complete Edition. There are letters even of Horace Walpole, the virtuoso, that he did not label

“Confidential: Please burn”

because he assumed as a matter of course that they would not be wrapped in ribbons and returned to him with the rest. Moreover, until the last fifty years, letters had always been edited, and the letter writers who might have had a lurking suspicion that their pages might be published someday never doubted that the local passages or the humdrum passages or the intimate passages would be cut out. They did not foresee the type of attention that the twentieth century would bring to such work; “morbid” they would have called it.

Moreover, there is an extraordinary aspect about the letter writers' work whereby one understands that even the consciousness of other readers does not impair or undermine the sincerity and the singlemindedness of the letters they address to the friends they really love. In the old sense, there is a “mystery” here. It is related to the mystery behind all creative literature above a certain level. Art is confession; art is the secret told. Art itself is a letter written to an ideal mind, to a dreamed-of audience. The great letter-sequences are written to close friends. But even the closest friends cannot meet the requirements of the artist, and the work passes over their shoulder to that half-divine audience that artists presuppose. All of Mme. de Sévigné's life was built about those wonderful letters. On one plane they were written to regain her daughter's affection, to attract her daughter's admiration and love. But Mme. de Sévigné knew that her daughter merely brought an amused, an indulgent, a faintly contemptuous appreciation. And time after time the letter rises beyond the understanding of the daughter and becomes an

aria

where the overloaded heart sings to itself for the sheer comfort of its felicity, sings perhaps to the daughter as she might have been. In such passages Mme. de Sévigné even defeated the purpose of the rest of the letter, even risked drawing upon herself her daughter's vexation and ill-humor. But sing she must. The audience of a work of art is never clear in a true artist's mind, but is made of souls that he has guessed atâold hero worships repersonified and loves transferred: as though the audiences at concerts and art galleries and the company of book-buyers were made up of Michelangelos and Platos and Violas and Imogens and Cardinal Newmans. Your letters and mine are messages to friends and we do them as well as we can to please the friends; but the great letters are letters to friends plus the most exacting spirits the mind can imagine.

But art is not only the desire to tell one's secret; it is the desire to tell it and to hide it at the same time. And the secret is nothing more than the whole drama of the inner life, the alternations between one's hope of self-improvement and one's self-reproach at one's failures. “Out of our quarrels with other people we make rhetoric,” said William Butler Yeats; “out of our quarrels with ourselves we make literature.” Self-reproach is the first and the continuing state of the soul. And it is the way we go about assuaging that reproach that makes us do anything valuable. . . .

I am supposed to be speaking about English writers, but I want to say a few more words about the greatest of all letter writers, Mme. de Sévigné. Indeed, she has almost a place in English letters, since two of our greatest loved her with a special love. Horace Walpole read and reread the volumes of her correspondence that kept making their first appearance in his time; he called her “Notre Dame des Rochers,” and when he finally received the manuscript of one of her letters he treasured it above everything else he possessed. And Edward FitzGerald went so far as to prepare a little atlas and biographical dictionary and practically a concordance of her letters for his own use. The anthologists have made havoc with her reception in France. All students in that country, especially the girls, are obliged to study and imitate and comment upon a volume of her

Selected Letters

. And all the showpieces, all the stunt letters are there. But the way to enter the fair country that is her mind is to begin by not looking for the anecdotes of the court, or the flowerets of language, or the inimitable little jokes through which she sees life (for later “all these things shall be added unto you”), but to enter it as Marcel Proust said his grandmother did, by the door of the heart. For me the key to Mme. de Sévigné is an acquaintance with her grandmother. Her grandmother was Mère Marie de Chantal, the co-worker of St. François de Sales. Mère Chantal was canonized as a Saint of the Church almost during Mme. de Sévigné's lifetime. She was one of those saints like St. Teresa who found no difficulty in living two full lifetimes in one, a Mary and a Martha. Her writings are among the minor classics of the Church. They are full of an overwhelming fixed adoration of God, and one has only to read them for a few pages to realize that it is the same blinding intensity that has been inherited by the granddaughter and fixed by some tragic accident upon a human being. And Mme. de Sévigné knew it, and the anthologies do not include those bitter and heartbroken passages in which the cards are really laid on the table:

This is my destiny [she writes to her daughter]; and the sufferings which follow upon my love for you, being offered to God constitute my penitence for an attachment which should be only for him.

Â

Do I exaggerate?

She writes her friend Guitant:

Â

I still am in the dark as to whether my dear daughter is coming back to Paris or not. However, I am preparing her rooms in our Carnavalet and we shall see what Providence has decreed. I ceaselessly keep this idea of Providence, Providence in my mind. All my thoughts are resigned to this sovereign will. There are my devotion. There is my scapulary. There is my rosary. There are my vigils. And if I were worthy of believing that I had a spiritual rôle to play I should say that it lay in that. But I am not worthy: for what is one to do with a mind that sees clearly, but with a heart of ice?

Â

One has to read thirty or forty letters to come upon such passages, but, having found them, all the rest flows with an even greater beauty. For example, I have never seen quoted in any book or article on Mme. de Sévigné a short phrase that explains the miracle of the style, and perhaps of all style:

Farewell, my blessed child; now I can go on telling you that I love you without fear of boring you, since you are willing to endure it in favor of my style: you excuse the importunity of my heart through your approval of my intelligence, isn't it just that?

Â

Nor this terrible word:

Â

All that is hateful in me, my daughter, proceeds from my lifetime of devotion to you.

In one of my books I made literary use of this situation with distinct allusion to Mme. de Sévigné: and I keep receiving indignant letters from lovers of the Frenchwoman saying that I imagined it; that she, being the incarnation of grace and charm and the salon, was too sane to allow of such an interpretation.

The Afterword of this volume is constructed in large part from Thornton Wilder's words in unpublished letters, journals, business records, and publications not easy to come by. Readers interested in additional information about Thornton Wilder are referred to standard sources and to the Thornton Wilder Society's website: www.thorntonwildersociety.org.

Many Wilder fans deserve my thanks for helping me to accomplish this task, for which, of course, I bear full responsibility. Space permits me to extend thanks to only a few: Hugh Van Dusen, David Semanki, Barbara Whitepine, and Celeste Fellows. Four individuals deserve a special salute, and I am honored to give it: Barbara Hogenson, Russell Banks, J. D. McClatchy, and Penelope Niven.

Letters and Journals

With the exceptions noted below, quotations from Thornton Wilder's letters and his journal are taken from one of two principal sources: the unpublished letters, manuscripts, and related files in the Wilder Family Archives in the Yale Collection of American Literature at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, and the Wilder family's own holdings, including many of Thornton Wilder's legal and agency papers. Minor spelling errors have been silently corrected. All rights are reserved for this material. Appreciation is expressed to the family of the late Professor Franz Link, for a copy of Thornton Wilder's letter to him, and to the Lawrenceville School, for a copy of Wilder's letter to John Townley.

Publications

Excerpts from published sources are identified in the order of their appearance in the text, with permissions noted as required: Wilder's interview with André Maurois, “A Holiday Diary, 1928,” appeared in André Maurois,

A Private Universe

(New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1932) and was reprinted in Jackson R. Bryer, Ed.,

Conversations with Thornton Wilder

(Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1992), pp. 13â14. “On Reading the Great Letter Writers” was first published in Donald Gallup, Ed.,

American Characteristics & Other Essays

(New York: Harper & Row, 1979; Authors Guild Backinprint edition, 2000), pp. 151â64. Reprinted by permission of Tappan Wilder.

Photographs

The Wilder-Tunney photo is courtesy of the Yale Collection of American Literature. The author's photo, taken of Thornton Wilder when he was a secondary-school teacher, is provided courtesy of the Lawrenceville School, with the special assistance of Jacqueline Haun of the Bunn Library.