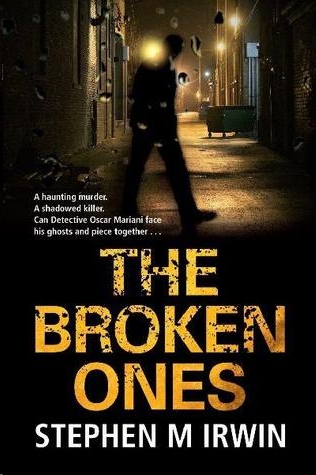

The Broken Ones

Also by Stephen M. Irwin

The Dead Path

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2011 by Stephen M. Irwin

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Originally published in slightly different form in paperback in Australia by Hachette Australia, an imprint of Hachette Australia Pty Limited, Sydney, in 2011.

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Title page photograph by Josef Kubicek/Vetta/Getty Images

Jacket design by Michael J. Windsor

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Irwin, Stephen M.

The broken ones : a novel / Stephen M. Irwin. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

I. Title.

PR9619.4.I79B76 2012

823′.92—dc23 2011039733

eISBN: 978-0-385-53466-6

v3.1

For Kitty.

The key to it all

.

Contents

They haunt me—her lutes and her forests;

No beauty on earth I see

But shadowed with that dream recalls

Her loveliness to me:

Still eyes look coldly upon me,

Cold voices whisper and say—

“He is crazed with the spell of far Arabia,

They have stolen his wits away.”

WALTER DE LA MARE

, “Arabia”

Prologue

From page 1,

The Argus

,

September 10

EDITORIAL

Three Years on—Still No Answers

The ability of humankind to emerge from calamity into better times has manifested again and again throughout our history. The plague-ridden and religiously extreme Middle Ages birthed the Renaissance, the opening of the world by sail, and the Enlightenment’s bright lights of science. Last century’s appalling World Wars, with their unprecedented casualties, spurred discoveries that have yielded extraordinary peacetime benefits: penicillin, rockets, and jet travel. It remains, however, difficult to imagine what reward could come from the dark event that occurred three years ago today, the repercussions of which continue to be felt by each of us, in every corner of the globe.

On that Wednesday—commonly known as Gray Wednesday in the West, Black Wednesday in Russia, and the innocuous Day of Change in the People’s Republic of China—few of us could have predicted how different our world would be today, three years on. None of us could have been expected to; no single event has so definitively tied psychological harm to economic depression and technological failure. The hallmarks of disaster, though, were instantly apparent: at just after 10:00 GMT, the earth’s poles switched. Every compass in the world swung 180 degrees, and two hundred and sixteen passenger jets either collided or simply fell from the skies, with their navigation systems fatally flummoxed. No one knows how many smaller aircraft also fell, but estimates range between seven and sixteen thousand. Almost all post–Cold War satellites met a similar fate, with their onboard computing systems

instantly and simultaneously failing, plunging global telecommunications into a new age of darkness from which we have only barely begun to recover. Few civilian organizations—indeed, few governments—have been able to launch new satellites because of the economic despair that now seems so deeply entrenched that many are regarding it as the new status quo.

We still tell our children that the sun rises in the east and Santa Claus lives at the North Pole, but we all know that north is south and the world is upside down in so many ways. The state of the global economy is dire. Unemployment here remains at 21 percent; in the UK, the USA, and Germany, it is closer to 25 percent. Japan, which was still recovering from nuclear disaster when Gray Wednesday occurred, is worse still, with unemployment at around 30 percent and rising. We don’t know what is occurring everywhere; Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, Serbia are among the countries that have sealed their borders. But in those nations which are still attempting to participate in world trade, it is not just their blue-collar industries that have been decimated by depression and suicide: all sectors of all industries were hit hard by Gray Wednesday. The lack of a reliable workforce in the mining sector has resulted in coal shortages and power outages. Oil companies have suffered similarly, resulting in a rapid escalation in the prices of crude oil and refined fuels like gasoline and diesel. Most manufacturing industries have reported significant downturns as a result of erratic supplies of material, power, and workers. Crop and livestock industries are, if anything, even worse off; the rice, tea, coffee, cocoa, and rubber industries have all shrunk enormously in scale, and the resultant explosion in commodities prices has escalated inflation in countries too numerous to mention. With the sharp collapse in the value of legal tender, people everywhere have turned to older-fashioned means of exchange. Black markets have burgeoned, and almost everyone now uses barter at least a little and sometimes exclusively, further reducing governments’ tax incomes. Poorer governments mean poorly paid government workers and a commensurate vulnerability to bribery. The conviction last month of the federal agriculture minister for contempt of Parliament is the tip of a large iceberg. As companies collapse and their surviving contemporaries scramble to fill the voids, graft and blackmail are becoming well-honed tools in all sectors of business.

The challenges to national economies have been worsened by a dramatic shift in global weather patterns in the past thirty-six months. Rainfall patterns have changed on all continents, and average temperatures have swung by up to seven degrees Fahrenheit: summer heats are rising, and the past three winters in the Northern Hemisphere have been the coldest on record. Climatologists speculate that the cause of this was the switching of the poles, but detailed research may take decades to conduct and unravel. Some people are not prepared to wait that long: in Turkey two years ago, and in South Korea last month, members of religious sects committed suicide on a massive scale—four thousand lives in total. Death on a smaller, more murderous scale occurred in January, when four men and a woman drove a bus packed with explosives through the main gate to the Large Hadron Collider, near Geneva: the explosion killed them and twenty-three staff members.

Nothing, however, has ameliorated the situation that Gray Wednesday has left us in. The federal Commission of Inquiry drags on, now under its second commissioner and still with no tangible results. Government-funded and private policy institutes have made innumerable recommendations to help preserve liquidity and protect jobs, but none have made any inroads toward finding a solution. Our country is not alone; the rest of the world is just as baffled. Our guests that arrived on September 10 three years ago seem fixed to stay; the psychological impact of their arrival may have to be judged by future generations. In the meantime, our economies run flat and our stomachs get emptier. The question remains: Where is the silver lining? Where, in short, is the hope?

Chapter

1

Not many years from now

A

boy emerged from the deep shadows under a dripping doorway awning, a cautious mollusk venturing from its shell. He was sixteen or so, his face a small, pale triangle above dark clothes, eyes hidden by dark lank hair and gloom. When he saw Oscar’s car, he retreated into darkness.

Inside the tired sedan, Oscar Mariani gripped the wheel unhappily. Dusk: the hour when Delete addicts and street prostitutes rose to score or hook. The car’s engine kept the repainted police cruiser’s interior warm, and the windows were lightly fogged. Rain tapped on the roof, the sound muffled by the sagging hood lining. It was not a muscular downpour but a constant, weeping drizzle barely more substantial than mist. Oscar wondered if this rain would ever stop. It would ease, certainly, then a foggy morning might open onto a rare day of sunshine, then an inevitable storm … and another week of this god-awful wet.

He’d parked on the cruddy street opposite the mouth of a lane so narrow it was almost an alley. Halfway down it, the red and blue lights of patrol cars intruded, slicing through the drizzle, reflecting off the dull eyes of windows and turning the droplets of water on his sedan’s windows into startling instants of sapphire and blood. Somewhere down there, dogs barked.

Oscar reached for the door handle and stopped to look at the man staring back at him in the rearview mirror. The stubble on his thin face badly needed either taming with a razor or grooming into a beard. Under thick coppery hair, his tall forehead was beginning to wrinkle as thirty faded and forty loomed. But it was his own stare that held him: gray, wide-set eyes that one woman long ago had called beautiful

and another much more recently had called disturbed. Now they just looked exhausted.

Down the alley, figures crossing in front of the turning emergency lights cast long, insect shadows with scissor legs and swollen heads. Another polished white police car, glistening with raindrops, rolled around the corner near Oscar and turned down the alley to join the others. By its headlights, he could see a woman in a yellow raincoat hunched under an eave near the collection of squad cars. Neve was here already.

Oscar sighed and pulled on his waxed cotton motorcycle jacket, patched in several places but warm and blessed with lots of pockets, all full. From the seat beside him he took his black hat—a wide-brimmed squat thing with all the style of a dropped towel—and pulled it low onto his head. It was ugly, but it kept the rain off.

And the rain was cold; it whispered shyly on Oscar’s shoulders and hat as he put the car key in the door and gave it an arcane series of twists until it caught and locked. He headed toward the flashing lights.

Old townhouses crowded in on both sides of the alley; their small back courtyards were separated from the garbage-strewn thoroughfare by a continuous fence that was an alternating patchwork of graffitied brick, graffitied timber, graffitied metal, and barbed wire. Despite the steady rain, the air smelled of burned things and urine. Three white patrol cruisers stood out like pearls in a coal hopper; in front of them were a Scenes of Crime van and an unmarked patrol car. Onlookers had gathered under awnings and in doorways: gray-faced people loosely hunched in tired clothes, smoking silently and watching with the attention of seagulls observing picnickers, wondering what might be left behind.

“Where have you been?” Neve asked.

Neve de Rossa was more than ten years younger than Oscar. He was tall and she was petite; the top of her head barely reached his shoulders. Her blonde hair was wet and plastered flat, its peltlike sheen reflecting the emergency lights. Her face and shoulders were taut, as if she were in a ceaseless flinch, always anticipating a blow.