The Calendar (28 page)

It was against this backdrop that the physician, judge and philosopher Ibn Rushd wrote what Europeans considered the most thorough and enlightening commentaries to date on Aristotle and the Aristotelian universe. Called ‘the commentator’, a play on Aristotle’s appellation ‘the philosopher’, Ibn Rushd conceived of a philosophical argument that tried to solve the dilemma between the sacred and the secular by insisting that two contradictory truths could exist: one for science and ‘natural reason’ and one for ‘revelation’. According to his philosophy:

When a conflict arises we will therefore simply say: here are the conclusions to which my reason as a philosopher leads me, but because God cannot lie, I adhere to the truth he has revealed to us and I cling to it through faith.

At first Ibn Rushd’s ‘double truth’ was merely frowned upon. Then it was aggressively challenged by religious authorities in Christian Europe and Islamic Cordoba. Declaring that Aristotle was not a god, but a man and therefore fallible, bishops and imams alike objected to Ibn Rushd’s insistence that science was on par with divine truth. They also were horrified by Ibn Rushd’s assertion that while science proved that God was the mechanistic mover of the universe, God himself was a ‘machine’ entirely removed from interference in human affairs. According to Ibn Rushd, it was the laws of nature--of this machine--that uphold the eternity of the universe and the passage of time. This idea denied a range of core Christian and Moslem beliefs, including creation, the doctrine of an active and fully engaged God, and the immortality of the individual soul.

Ibn Rushd’s ideas nonetheless resonated with many intellectuals in Europe, working their way into a gradual rethinking of time by Christians, begun with the likes of Hermann the Lame. For instance, around 1200, a Norman mathematician and encyclopaedist named Alexander of Villedieu suggested there may be two truths in regard to time reckoning. He makes no direct mention of Ibn Rushd’s work, and as a pious Catholic he would have been horrified to be mentioned in the same sentence with this near-heretical Arab. Yet he was advanced enough in his thinking to use Hindu numbers, and was reasoning along the same line as Ibn Rushd when he divided the measurement of time into two categories: what he called philosophical

computus,

by which he meant time as measured by science, which is infallible; and ecclesiastic time, which he curiously referred to as ‘vulgar’

computus,

‘the science of dividing time according to the custom of the Church’. But Alexander dodges the potential controversy of his categories by telling us that he does not want to discuss the philosophical

computus,

but will confine his comments to the ecclesiastic.

Eventually the Italian master Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) solved the dilemma, at least temporarily, by rejecting the incompatibility of the two truths. He argued that in fact both ‘truths’ point in the same direction: towards God and towards the universe of ideas and morals created by God. To do this Aquinas made the breathtakingly bold assertion that Platonic universals could be proven by Aristotelian logic. In other words, this brilliant Italian philosopher and theologian, born in a castle to the noble counts of Aquino and trained in Naples and Cologne, attempted in a comprehensive manner to unite the worlds of Aristotle and Plato.

Part of Thomas’s argument rested on a theory that time and the universe could not be eternal, as Aristotle claimed, but must have started with an original, unmoved mover, which Thomas says is God. He then sets out in his massive

Summa Theologica,

which he worked on until his death in 1274, to apply the rules of science as argued by Aristotle to prove the reality of God’s perfection, of the Creation and the existence of the human soul, and of the ethical foundation of Christian virtue. This attempted conciliation of the sacred and the secular provided the great philosophical compromise of the Middle Ages, permitting intellectuals on both sides of the great divide of the two truths some breathing room.

But Thomas’s opus was not initially well received either by the followers of Ibn Rushd, who accused him of faulty logic, or by the Church. At first conservative Church leaders condemned his

Summa

as being overly radical, though just a generation after Thomas’s death his philosophy was embraced by the Church. It became the official theological response to the new knowledge and a counter to Ibn Rushd--a point vividly made in a painting rendered during this period of an enormous Thomas enthroned, ‘crushing’ under his feet a tiny, bearded and turbaned Ibn Rushd. Thomas was made a saint in 1323.

For a time Thomas’s philosophy comforted conservatives and scholars who shared Alexander of Villedieu’s discomfort in acknowledging truths that seemed to contradict the Church. But it also gave a green light of sorts for science to seek its own truths, though within strict limits--as Bacon would discover, and many years later Galileo. Another period painting amply demonstrates this, illustrating a gigantic St Augustine, dressed in glittering medieval robes, crushing underfoot a tiny Aristotle in a simple tunic. Yet the Aquinas compromise had the advantage of at least quieting the all-encompassing theological debate so that men such as Bacon could begin to turn their attention towards using the new knowledge of the Greeks, Arabs and Indians for scientific endeavours, rather than to score points in heated philosophical debates.

But Ibn Rushd and like-minded Islamic scholars did not win even this partial victory in their own homeland. Towards the end of Ibn Rushd’s life the conservatives in Spain struck hard against the celebrated schools in Cordoba, denouncing Ibn Rushd and other intellectuals and later disavowed his work. For even as Europe finally began to absorb the learning brought to its frontiers by Arabs, the world of Islam was filling deeper into a period of political turmoil and outside threats from Mongols and others, hastening a growing chill in its intellectual life.

With the fate of the human soul and the beliefs of a thousand years hanging in the balance, scientific pursuits remained largely fringe endeavours for intellectuals during the 1100s and 1200s. Peter Abelard, for one, brushed off mathematics, astronomy and virtually all science, insisting in 1140 that ‘philosophy can do more than nature’. As for time reckoning, he dismissed it as being in the same low category as usury, useful in the hallowed halls of the university only for collecting fees from students based on elapsed time. Thomas Aquinas a century later was equally dismissive of time reckoning, refusing to allow that it was real in Aristotelian terms. Like Abelard, Thomas argued that time fixing should be excluded from the theoretical sciences, also ranking it as a lowly mechanical art unworthy of scholarly contemplation. Even those who pondered the new texts with an eye towards learning more about science tended to simply read Ptolemy, Galen, Euclid and the Arab astronomers, rather than trying to apply their ancient ideas to anything new.

Still, a scattered handful of scholars pored over the mass of new knowledge and tried to make sense of it, and attempted to apply it to everything from human anatomy to more accurately measuring time.

One of the first hands-on time reckoners steeped in the new knowledge was Reiner of Paderborn (c. mid-twelfth century), dean of the cathedral at Paderborn, on the Lippe River in western Germany. Now all but forgotten, Reiner wrote a treatise in 1171,

Computus emendatus,

that applies the new Hindu numbers and mathematics to the old formulas of

computus

involving the Easter calculation--and proves that the old 19-year lunisolar cycle was misaligned with the true movements of the sun and moon. This error amounted to one day lost every 315 years--that is, every 315 years the 19-year cycle of lunar and solar years slipped a day against the Julian calendar. Reiner’s measurements also led him to the near-heretical conclusion that all attempts by computists to date the age of the world, and to create a timeline of history dating back to creation, were mistaken, given the errors in the calendar.

In 1200 Conrad of Strasbourg wrote that the winter solstice had fallen behind by 10 days since Caesar’s time. Conrad’s estimate established the figure of 10 days as gospel among reform-minded time reckoners, though they argued about whether one should calculate the drift from Caesar’s founding of the calendar in 45 BC or from the time of the Council of Nicaea in 325, when time reckoners fixed the equinox on 21 March.

A few years after Conrad, the English scholar Robert Grosseteste (c. 1175-1253) recalculated Reiner’s lunar-solar slip and amended it to the gain of a day every 304 years--closer to the actual drift against the Julian year of a day every 308.5 years. He also proposed a solution: that one day be dropped from the lunar calendar every three centuries. Grosseteste, chancellor of Oxford University and later a bishop, also closely studied measurements of the solar year, confirming once and for all that the values arrived at by Hipparchus, Ptolemy, al-Battani and other Arabs and Greeks were superior to those worked out by Bede and centuries of computists. This led him to suggest a new starting point for the Easter calculation--a spring equinox of 14 March instead of 21 March--to compensate for the centuries-long drift in the calendar against the calendar year. Grosseteste is also remembered because of the standards he set for science. Known for his work in geometry and optics as well as astronomy, he was an early advocate of using experimentation and observation to verify theories. This was an idea years ahead of its time. For while most intellectuals were trying to reconcile contradictions between the new knowledge and the old dogma, Grosseteste was taking the next step and trying to reconcile the contradictions between reason and experience--between the new knowledge as written in books and empirical evidence.

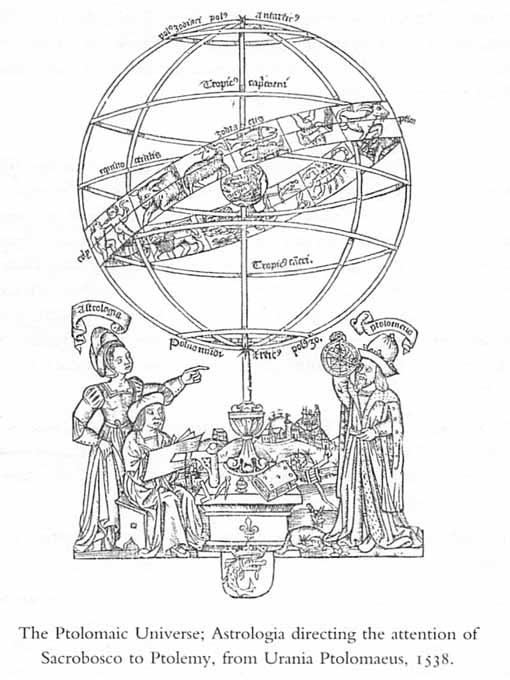

By Grosseteste’s time few serious time reckoners were denying that the errors existed in the lunar and solar calendars. But this hardly meant they were all for reform. Another Englishman, John of Sacrobosco (c. 1195-1256), proved the errors down to the minutes and seconds using an astrolabe and a deep knowledge of Arab, Greek and Indian mathematics and astronomy. Yet he was able to offer only one modest reform in the solar calendar: that the calendric order be restored by cancelling the leap day every 288 years. Otherwise John stuck with Bede’s admonition to follow the ‘universal custom’ of accepting the errors, insisting that the Church was the final authority. Referring to the Council of Nicaea in 325, he wrote: ‘Since the General Council forbade any alterations to the calendar, modern scholars have had to tolerate errors ever since.’ John’s reticence must have resonated with scholars. For three hundred years his textbook on time reckoning remained a standard in universities. Even Protestants republished it in 1538, soon after they changed the university at Wittenberg to a Lutheran institution.

Into this mix in the mid-1200s came Roger Bacon, another firebrand visionary along the lines of Abelard. He not only took up the cause of Robert Grosseteste in pushing for reform of the calendar but he also became a staunch advocate of Grosseteste’s championing of empiricism and the objectivity of science. Even further ahead of his time than Grosseteste--centuries further--Bacon demanded that scholars stop talking and debating and start

doing.

In his

Opus Mains--

written in the 1260s, the same decade that Thomas Aquinas was labouring over his

Summa Theologica

--Bacon writes:

The Latins have laid the foundations of knowledge regarding languages, mathematics, and perspective; I want now to turn to the foundations provided by experimental science, for without experience one cannot know anything fully.

In possibly Bacon’s most famous passage he vividly illustrates his point:

If someone who has never seen fire proves through reasoning that fire burns, changes things and destroys them, the mind of his listener will not be satisfied with that, and will not avoid fire before he has placed his hand or something combustible on the fire, to prove through his experience what his reasoning had taught him. But once it has had the experience of combustion the mind is assured and rests in the light of truth. This reasoning is not enough--one needs experience.

As passionate and arrogant about his cause as Abelard was about the use of logic a century and a half earlier, Bacon argued that nature had been established by God and therefore needed to be explored, tested, and absorbed to bring people closer to God. He warns that a failure to embrace science is an affront to God and an embarrassment to Christians, who were forced to acknowledge the superiority of Arab science.

A prime example of this embarrassment, he said, was the habit of Christian time reckoners and mathematicians to round off numbers rather than trying to calculate them precisely. This was an intentional jab at time reckoners such as Bede and Bacon’s contemporary John of Sacrobosco--those who admitted to calendric errors but settled for approximations rather than challenge the Church. This had led, writes Bacon, to a calendar that in that very year (1267) was causing havoc for devout Christians.