The Calendar (3 page)

2 Luna: Temptress of Time

He appointed the moon for seasons: the sun knoweth his going down.

Psalm 104:19, c. 150 BC

Some 13,000 years ago, when the southern flank of the great Wurm icecap still touched the Baltic Sea, the Dordogne Valley in central France looked more like present-day Alaska than the leafy winegrowing hills of today. Sprawling herds of reindeer, bison and woolly rhino grazed on tundra and drank the water of bracingly cold streams. From limestone heights sabre-toothed tigers scanned the herds as eagles circled slowly thousands of feet up in the chilly air, looking for shrews, mice and Palaeolithic rodents now extinct.

Perched on a small bluff near what is now the village of Le Placard, another creature gazed not at the deer and bubbling stream but skywards. A Cro-Magnon version of Roger Bacon, this hairy, reindeer-skin-clad man patiently waited for the moon to rise above the valley. He was about to revolutionize the way he and his people would view time.

For several nights this Stone Age astronomer and time reckoner had been watching the pale orb in the sky wax and wane. He noted that it moved through a series of predictable phases, and that he could count the nights between the moments when it was full, half full and completely dark. This was useful information for a tribe or clan that wanted to use the silvery light to cook and hunt, or for calculating future events such as the number of full moons between the first freeze of winter and the coming of spring. For the calendar maker himself it was valuable information he could use to impress his family, his mate and his clan by predicting when the moon would next be full or would disappear, events that even today signal key religious ceremonies and celebrations.

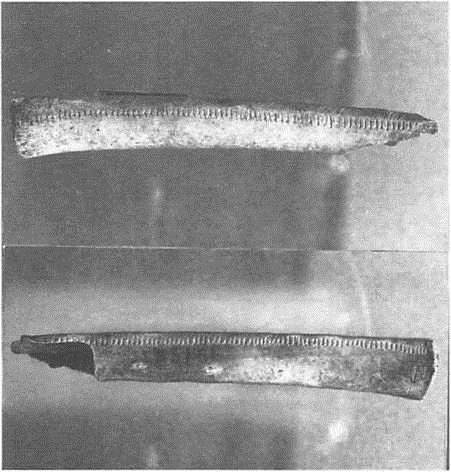

The man at Le Placard was hardly the first to use the moon as a crude clock. But on this particular night this Cro-Magnon did not merely gaze upwards and ponder the phases of the earth’s satellite. Turning from the sky, he carefully carved a notch into an eagle bone the size of a butter knife, adding it to a series of notches running vertically along the bone. The notches were straight lines with smaller diagonals carved near the bottoms, looking like this:

ɺ

. The man added his marking that night to what appear to be distinct groupings of similar symbols that change in regular patterns, possibly corresponding to the phases of the moon. The groupings contain seven marks apiece, which is a close approximation of the moon’s progression through new, quarter, full, quarter and back to new. Sometime later the man discarded or lost this eagle bone for archaeologists to find some 13,000 years later in a dig.

Was this one of the first calendars?

Carved Eagle Bone Possible Lunar Calendar, Le Placard, c. 11,000 BC

Anthropologists say it is possible, that something like the imagined scene above may have happened on a long-ago night in Le Placard. But not all agree. Sceptics insist that the markings on this and other bones are not calendars but decorations or even random scratches--Stone Age doodles or the marks left when ancient hunters sharpened their knives. Yet over the years archaeologists keep finding the same or similar patterns appearing on stones and bones from sites in Africa and Europe.

One bone, dating back to the Dordogne 30,000 years ago, is covered with rounded gouges that seem to represent the moon’s course over a two-and-a-half-month period. Another famous image, the 27,000-year-old ‘Earth Mother of Laussel’, shows the carving of what appears to be a pregnant woman holding a horn marked with thirteen notches. Is this supposed to represent a rough approximation of a lunar year? If so, and if the scratches and notches on the bones and stones really are calendars, then how exactly was this information used? We may never know, though I suspect that our calendar, made of little boxes and numbers, would be just as puzzling to the time reckoner of Le Placard and his clan. Still, a link exists between our calendar and theirs. Both represent conscious efforts to organize time by measuring it and writing it down. And both use astronomic phenomena as a timekeeper, though the Cro-Magnons who carved these bones and stones were clearly people of the moon where measuring time was concerned, while we are people of the sun.

It makes sense that this Stone Age calendar maker chose Luna as his inspiration. Alluring and lovely in its silvery dominance of the night-time sky, the moon seems at first glance to be a perfect clock in its dependable regularity. Roughly every 29 1/2 days it passes through its phases, from new moon to full moon and back again--a steady celestial progression that anyone can see and keep track of. It is also relatively simple to figure out that twelve full cycles of the moon seem to roughly correspond with the seasons, which is how early societies invented the concept of a time span called a year.

Nearly every ancient culture worshipped the moon. Ancient Egyptians called their moon god Khonsu, the Sumerians Nanna. The Greek and Roman goddess of the moon had three faces: in its dark form it was Hecate, waxing it was Artemis (Diana) and full it was Selene (Luna). Even today people celebrate the moon, holding feasts, dances and solemn rituals when the moon is new. The San of Africa, for instance, chant a prayer: ‘Hail, hail, young moon!’ Eskimos eat a feast of fish, reportedly put out their lamps and exchange women. Moslems watch for the new moon of Ramadan, Islam’s holy month of fasting and sexual abstinence during the day and feasting at night.

A lunar lexicon still draws on the mystery and majesty of this strange orb hanging in the sky. We have

Iunatic

and

moonstruck,

which come from legends that sleeping in the moonlight will drive a person insane. We also have

moonshine, blue moons,

Debussy’s

Clair de Lune,

and Shakespeare’s comparison of the crescent moon to a ‘silver bow new-bent in heaven’. Even more profound is the deeply rooted connection of the moon with measurement.

Me-

or

men

is derived from moon, as in the English

meter, menstrual

and

measure.

The moon was not the only early clock, but one of several natural cues used by ancient peoples to measure time and to predict events such as winter, seasonal rains and the harvest. In Siberia the Ugric Ostiak still base their calendar on natural cycles, incorporating them into month names such as Spawning Month, Ducks-and-Geese-Go-Away Month and Wind Month. Likewise the Natchez on the lower Mississippi River had Deer Month, Little-Corn Month and Bear Month.

Such specific natural cues must have come out of a long and close study of local fauna, flora and other natural surroundings and events, information learned and then passed down over the generations both informally from parents to children and more formally as lists of months and easily remembered poems and calendar stories told and retold. Eventually these oral versions of time-reckoning cues were carved in stone and recorded on scrolls and parchments.

For instance, the Greek poet Hesiod (fl. ca. 800 BC) some 2,800 years ago took his local oral calendar used since ancient times in Peloponnesia and wrote it down in a long poem called

Works and Days.

A practical guide for organizing time,

Works and Days

is also a moral mandate to follow ancient rules of time and duty, which is not the first or last time that a calendar was used to codify standards of conduct. Hesiod wrote his poem at a time when Greece was becoming a maritime power in the eastern Mediterranean and many young men were turning away from fanning and the discipline of the land to embrace commerce, war, and politics. The first part of the poem, ‘Works’, is addressed to Hesiod’s younger brother Perses, apparently one of those young men uninterested in the traditional life. Hesiod believed his wayward sibling needed some stern guidance from his older brother. But the spine of the story is about time:

Keep all these warnings I give you, as the year is completed and the days become equal with the nights again, when once more the earth, mother of us all, bears yield in all variety.

Hesiod here refers to the most basic natural clock available--day and night--which in their respective lengths over the course of a year offer a crude guide to the seasons. He also alludes to cues such as the arrival of snails in early spring:

But when House-on-Back, the snail crawls from the ground up

the plants . . . it’s no longer

time for vine-digging;

time rather to put an edge to your sickles,

and rout out your helpers.

And of course Hesiod’s poem invokes that other fantastic clock in the night-time sky, the stars, using the position of constellations to guide his ‘exceedingly foolish’ brother:

Then, when Orion and Seirios are come to the middle of the sky,

and the rosy-fingered Dawn confronts Arcturus,

then, Perses, cut off all your grapes, and bring them home with you.

Show your grapes to the sun for ten days and for ten nights,

cover them with shade for five, and on the sixth day

press out the gifts of bountiful Dionysos into jars.

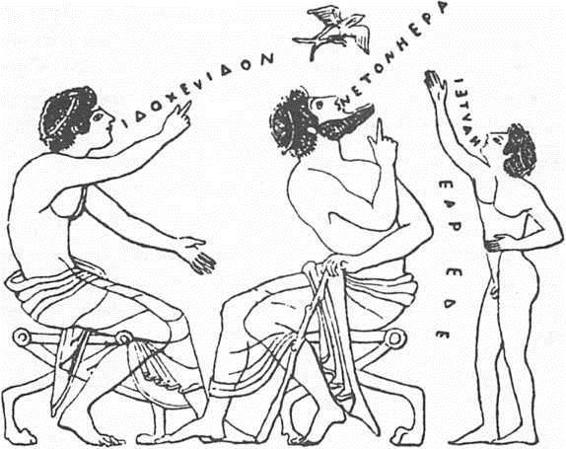

Early Greeks Greet Spring ‘Look at the Swallow,’ says the man on the left,

‘So it is, by Herakles.’ ‘There it goes!’ ‘Spring is here!’ From a vase, fifth century BC

But the most important time guide for Hesiod is the moon. This becomes evident in the second part of the poem, ‘Days’, which treats time as a mystical force and the calendar as a cycle of lucky and unlucky days, of omens and sacred ceremonies. ‘Days’ is structured around the 29 or 30 days of each Greek month and the phases running from one new moon to the next. It lists holy days, unlucky days, days that are ill-omened for the birth of girls, and the best days to geld bulls and sheep. ‘Avoid the thirteenth of the waxing month,’ writes Hesiod in a typical passage in ‘Days’, ‘for the commencing of sowing / But it is a good day for planting plants.’

The moon also gave Hesiod and the Greeks their year, which they based on 12 lunar months averaging close to 29 1/2 days, equal to some 354 days. Nor were they alone. From ancient Sumer and China to the now-vanished Anasazi in Arizona, the moon became paramount, with variations on this same 12-month, 354-day year popping up everywhere as the Stone Age melded into the Neolithic age and people began to discover how to build cities, irrigate fields, set up governments and organize armies to fight wars.

But alas, Luna was a mere temptress where time was concerned, drawing calendar makers down a false path--the first of many in humanity’s struggle to create an accurate calendar. For dependence on the moon caused a serious error--much worse than the flaw that outraged Roger Bacon several millennia later. All he had to worry about were the 11 minutes or so that his calendar was running fast. The ancient Greeks and others who threw their lot in with the moon found themselves with calendars running almost 11

days

fast, a misalignment that within a few years flings a calendar into disarray against the seasons, flip-flopping the summer and winter solstices in just 16 years. This situation is unacceptable to anyone using such a calendar as a guide to planting and harvesting, or for knowing the proper seasons for sailing, building houses and worshipping gods.

The problem comes in the time it takes for the moon to pass through its phases as it orbits the earth, which is not a tidy number for dividing into a year of approximately 365 1/4 days. In fact a true lunar month is a cumbersome 29.5306 days long as measured by modern instruments, equal to a precise 12-month lunar year of 354.3672 days. Stack that up against the true solar year of some 365.242199 days and one can appreciate the intense frustrations of astronomers over the centuries trying to link up the sun and moon.

As ancient cultures matured, frustration with the lunar drift stimulated their scientists and priests to ponder a solution--a line of inquiry that continues to this day as we try to fine-tune our days, weeks and months to fit into the true solar year. But for the ancients, lacking modern tools and concepts, even approximating this year using the moon proved immensely difficult. A number of solutions were tried, but all failed.