The Calendar (9 page)

Astrology was responsible for yet another curiosity in our weekly calendar: the order of the days. We take the order of Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and so forth for granted, but in fact it does not correspond to the ancient understanding of the solar system, which put Saturn farthest from the earth, followed in descending order by Jupiter, Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and the moon. The discrepancy between this order and the arrangement of our week conies from another invention from Mesopotamia: the division of the day into 24 equal units of time.

The order of the day names themselves comes from ancient Mesopotamian astrologers’ attaching a planet-god to preside over each hour of the day, arranged according to their correct cosmological order. For instance, Saturn controlled the first hour of Saturn’s day (Saturday), followed in its second hour by Jupiter, then by Mars, the Sun, Venus, Mercury and the moon. In the eighth hour the cycle started again with Saturn, and the progression repeated until the twenty-fourth hour of the day, which happened to fall to Mars. Because the next hour in the cycle--the first hour of the new day--belonged to the sun god, the day after Saturday was called Sunday.

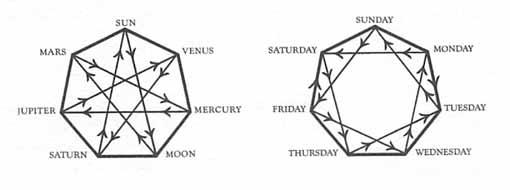

The ancients used a simple device for keeping track of the proper names of the hours and days in relation to the planet gods. They used a seven-sided figure, with each vertex marked with a planet’s name in the proper order. Archaeologists found one of these wheels drawn as graffiti on a wall when they excavated Pompeii. It looks something like this:

Even after Constantine’s edict about Sunday, it took another generation or two for the seven-day week to catch on throughout the empire. The 24-hour system took longer, having to wait until the invention of the mechanical clock in the Middle Ages by monks anxious to observe with precision their canonical hours. Before this, people marked the passage of time during the night by using the stars and during the day either by eyeballing the sun or by listening to public announcements of the time. For instance, the Roman military had callers watching the position of the sun to announce the changing of the guard at the third hour of the morning

(tertia hora),

at the sixth of midday

(sexta hora),

and at the ninth of the afternoon

(notia hora).

In another example, Saxons in Britain divided their days according to the ocean’s tides--’morningtide’, ‘noontide’, and ‘eveningtide’. Saxons also gave us the English word

day,

which comes not from the Latin

dies

but the word in Saxon for ‘to burn’, during the hot days of summer.

Hour

is from Latin and Greek words meaning ‘season’. Originally it referred to the fact that the length of the daylight period varies according to the season.

The second important calendar change introduced by Constantine was when to celebrate Easter, a matter not as easily resolved as the question of Sunday. The holiest day for Christians, Easter’s worship is complicated by the fact that Christ’s resurrection occurred during the Jewish Passover, which is dated according to the phases of the moon in the Jewish calendar. This means that the date for Passover--and Easter--drifts against the solar calendar, changing year to year. For early Christians this was a conundrum because they lacked the detailed astronomical know-how required to synchronize precisely the moon’s phases with the solar year.

This hardly stopped Christian time reckoners from trying. Indeed, even as science and knowledge from the ancient era began to fall away in these latter days, the question of when to celebrate Easter remained one of the few areas where scientific inquiry would survive during the great darkness to come. But this was still in the future. For Constantine the issue was not so much how to determine the date for Easter, but how to get the various factions of Christianity to agree to celebrate the Resurrection on the same day, even if technically this date was not exact. Politically this was crucial to establishing one state religion, with one set of rules.

The Easter question came to a head in what is today a quiet Turkish village famous as a lakeside respite for Turks weary of chaotic Istanbul, some 80 miles away. Known as Iznik, this village 1,700 years ago was a prosperous Hellenistic city called Nicaea, Greek for ‘victory’. This name appealed to Constantine, who styled himself ‘Constantinus Victor’. One historian writes, ‘The beautiful town lay on an eminence in the midst of a well-wooded flower-embellished country, with the clear bright waters of the Ascanian Lake at its foot.’ Says another, ‘The bright green of the chestnut woods in early summer stood out in the foreground; in the distance the snow-capped Olympus towered over its mountain ranges.’ It was here in 325 that Constantine convened the first major Christian council, which made the first concerted effort to solve the Easter problem and to come up with a unified date for its celebration.

The choice of Nicaea was no accident. Situated strategically in the east, near the new heart of Constantine’s revamped empire, the city was easily reached by the three hundred or so bishops who attended, and their delegations. Nearly all of these came from the east, in part because Christianity had permeated few areas in the west. Sylvester I, the ageing bishop of Rome--at this time all major bishops were called by the honorific

papa,

or ‘pope’--did not come because he was too ill, but he sent representatives.

Constantine was so anxious to convene this meeting that he paid the bishops’ expenses, placing at their disposal the empire’s system of public conveyances and posts along its highways. At Nicaea he paid for food and lodging. The sessions were held at a large basilica converted into a church and in the audience chamber of an imperial palace, possibly situated on the shore of today’s Lake Iznik.

The council opened in the late spring, probably on 20 May, without Constantine. He came a month later. The early sessions were held in the city’s main church, with the doors open to the lay public. Even pagan theologians participated in some of the debates. Gathering in small groups under colonnades and in gardens, dressed in togas and robes, they argued the relationship between God and Christ and the meaning of passages in holy texts, breaking for sumptuous meals of wine, meats, fruits and vegetables laid out by imperial servants.

For many of the bishops and priests it must have been a heady moment, if slightly surreal. Just a few years earlier many of them had been practising their religion in secret. Some had been viciously persecuted. Paul, a bishop from Neo-Caesarea, had lost the use of his hands after being tortured with hot irons. Two Egyptian bishops each had had an eye gouged out. One of these, Paphnutius, had also been hamstrung. Constantine later singled him out at Nicaea and kissed his mutilated face. The historian Eusebius, an eyewitness at the council, writes about the lavish feast held on 25 July to celebrate Constantine’s twentieth year as emperor, and the lingering fear felt by the bishops as they passed guards in the banquet halls and saw ‘the glint of arms’ that so recently had been turned against them.

But this turnaround from fear to feasting was nothing compared to Constantine’s sudden transformation of a church that for three hundred years had lacked a central authority. Scattered and at times hounded by the authorities, Christianity had operated less as a single cohesive religion than as a collection of sects and denominations following the same basic tenets but differing on points major and minor--such as when to celebrate Easter. Unity had always been a goal, though most congregations had remained more or less independent of one another, with doctrine and details of worship left to the local elders and members to decide. In cities large enough to assign a bishop, these prelates had exercised some authority, but as one historian noted in talking about Alexandria’s freewheeling churches, with their many controversies and bickering between sects and church leaders, ‘it was not an exceptional thing to have a doctrine of one’s own.’

Constantine’s mandate at Nicaea was to put a lid on this free-for-all by establishing a set of uniform rules governed by a centralized structure headed by himself as emperor. To accomplish this, Constantine called on the bishops to resolve differences ranging from petty disputes to fundamental controversies, the most important one at the time being the question of whether or not God the Father came before Christ the Son, or if they had both always existed. A popular Alexandrian theologian and preacher named Arius had been espousing the former, teachings recently condemned by his chief rival and detractor, the bishop of Alexandria. Both Arius and the bishop had been invited to make their case at the council.

Constantine arrived at Nicaea on about 19 June 325, and was immediately handed a thick packet of papers detailing controversies large and small among the attendees. He carried the packet with him into the audience hall of his palace, where he officially opened the council wearing a robe of gold and draped with jewels like a Persian king. Sitting on a golden throne in front of the prelates, he listened to welcoming speeches before rising to answer the mostly Greek-speaking bishops in Latin. Through a translator he welcomed them but quickly got to the point about the purpose of this council, holding up the packet of papers like a scolding father. He told them, ‘I your fellow servant am deeply pained whenever the Church of God is in dissension, a worse evil than the evil of war.’ Ordering the bishops to set aside their arguments, he took the packet and dropped it into the flames of a brazier. As it burned he told his audience that they must use this council to establish a uniform doctrine they all would follow--an imperative that became the guiding force behind the Catholic (‘universal’) church for centuries to come and would profoundly affect all aspects of life, including attitudes toward measuring time.

Details of the Easter debates at Nicaea are not recorded, although the controversies leading up to the council are well-known. For almost three centuries this issue had frustrated the followers of Christ, who were anxious to celebrate properly the signal event in their religion.

The problem arose because no one who witnessed Christ’s death and resurrection had thought to jot down a date. Even worse, the Gospels that recount Christ’s biography offer contradictory information in vague references about the timing of these events. All agree that Christ rose on the first day of the Jewish week-a Sunday. But which Sunday? Three Gospels--Matthew, Mark and Luke--suggest the Sunday after the Passover feast in the Jewish month of Nisan. The Gospel of John, however, indicates another date in Nisan, a dichotomy exacerbated by the drift of the Jewish lunar calendar in the years following Jesus’s crucifixion.

This vagueness arose because the earliest Christians cared little or nothing about dates, for the understandable reason that Jesus’s disciples and first followers fervently believed in their saviour’s imminent return. For them time was irrelevant, a point underscored by the apostle Paul, who did not date his letters that appear in the New Testament. He explains why in an epistle written to the church in Galatia, in which he reprimands those Christians who pay attention to ‘days and months and times and years’, accusing them of being more interested in astrology and earthly matters than in God. In another letter Paul exhorts the Christians of Colossae, in central Asia Minor, not to judge others by what they eat or drink, ‘or in respect of a holiday, or of the new moon or of the Sabbath, which are a shadow of things to come.’

When Jesus failed to return immediately, Christians realized they needed some sort of system for dating. By the second century they started writing schedules of when to worship, and crude calendars of saints’ days and other Christian holidays. They also began to argue about dates, such as whether to worship on Saturday or Sunday, and how to draw up a chronology of events in Jesus’s life. This became increasingly important to a religion that is based on real events as recorded in the Bible, which says that Christ lived in actual time: he was born, raised by Mary and Joseph, was baptized, became a teacher, was tried and executed, and rose from his tomb three days later. These central events are the underpinnings of the Gospels and of Christianity itself, which makes this a religion of history and the calendar--a potent and critical reality for early adherents even as they grappled with another core tenet of their religion: the doctrine of eternal life and a God who exists

outside

of time.

This dichotomy between the Christ that exists beyond time and the historic Christ became an early source of tension in Christianity. It later became one of the great theological conundrums of the Middle Ages, when the timeless Christ of dogma and mysticism reigned supreme. Even so, the notion of empiricism and measuring time never entirely died out, in part because of the Church’s need to understand enough about the temporal world to designate a proper date for Easter.

By the time of Nicaea, Christians had more or less agreed upon dates for celebrating Christ’s birth and other key events. These included days set aside to mark the martyrdom of saints--dates meant to record in real time important episodes in the Christian calendar and to provide an alternative to pagan holidays. The first known martyr’s day to be commemorated seems to have occurred in the mid-second century, when the bishop of Smyrna was burned at the stake ‘on the second day in the beginning of the month of Xanthicus,* the day before the seventh kalends of March, on a great Sabbath, at the eighth hour. He was arrested by Herod, when Philip of Thralles was High Priest, and Statius Quadratus Proconsul, during the unending reign of our Lord Jesus Christ.’ According to an eye-witness, the bishop’s bones were taken away and interred in a place ‘where the Lord will permit us ... to assemble and celebrate his martyrdom--his “birthday”--both in order to commemorate the heroes who have gone before, and to train and prepare the heroes yet to come.’