The Carnival at Bray (29 page)

Read The Carnival at Bray Online

Authors: Jessie Ann Foley

Maggie shrugged.

“Is it because he isn't here?”

Maggie looked at Sister Geneve suspiciously. Was this some sort of trap?

“Well, even if he was, I wouldn't be allowed to talk to him,” she said finally. “Remember?”

“Yes, I do.”

“Oh.”

“How are you feeling about all that, anyway?”

Maggie shrugged, dragging a finger through her melted ice cream.

“Not good, if you want me to be honest.”

“I always want you to be honest, Maggie.”

Maggie glanced up from her ice cream. The soft, worn face seemed to invite confession.

“Okay, then. I don't regret what happened in Rome. I know you and Sister Joan wanted to make me feel sorry for what I did. But the only thing I'm sorry about is that I hurt Eoin, that I ruined his life and got him expelled.”

Sister Geneve blinked. If Maggie wanted to shock her with this admission, it hadn't worked.

“Maggie, they were looking for a way to expel him anyway. His family can't afford his school fees. I've never been a believer in the kind of Christian charity practiced by the board members at Saint Brendan's.” She put a hand on Maggie's arm. Her palm was papery and warm. “It isn't your fault, pet. He's going to be all right, I promise. He's already enrolled at a vocational school in Greystones.”

“But why isn't he here tonight?” Maggie's eyes filled with tears. “I had something important I needed to give him.”

“Nothing illicit, I hope?”

“No. It was just a note.”

“I see. Well, then maybe I can help.” The nun's gray eyes were soft and neutral behind the octagonal glasses. “I see him

around from time to time. He works over there at the Quayside. Sister Alphonsus and I stop there for tea sometimes on our way home from bingo Sunday nights.”

“You know Eoin? You've

seen

him? How is he? Does he look okay? Did he ask about me?”

“I know him to see him. That's why I said I could help.”

“Is this some sort of trick? You trying to set me up or something?”

“No.” She smiled and patted Maggie's arm. “It's just that you look like such a sad sack, and I have a soft spot for poor lost creatures. Give me the note, and I'll get it to this fella.”

“You won't read it?”

“No.”

“You won't tell Sister Joan?”

Instinctively, they both glanced around the ballroom. Sister Joan was drinking tea with several of the more pious older ladies of the parish at a table near the back door. Sister Geneve leaned close to Maggie's ear.

“I won't tell a soul. But I'll only help you this one time. I'm not going to act as your secret messenger after this. I've read

Romeo and Juliet.”

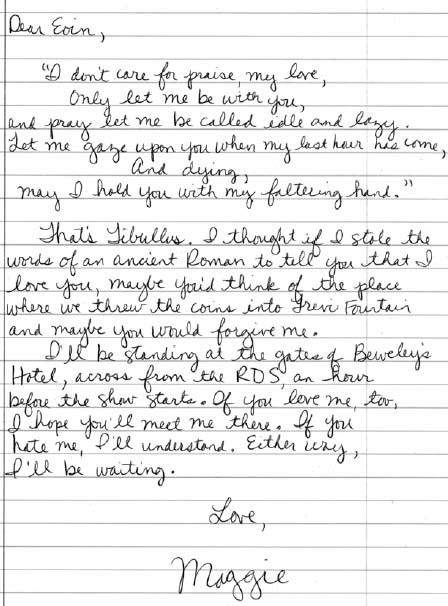

Maggie hesitated. But what were her other options? It was this or nothing at all. She took the envelope out of her handbag. It contained one ticket to see Nirvana at the Royal Dublin Society on April 8, and a folded-up piece of notebook paper.

She had made up her mind. If he didn't show up, she would go back to Chicago at the end of the school year without a word of complaint. She would make a place for him in her memory, cordon off a small portion of her heart and daydream from time to time of the way the morning sun brought out the red in his hair when it filtered through the wooden shutters of the Casa di Santa Barbara. And eventually, she would move on. She would silence the voice inside of her that said if she lost Eoin, her life would always be less than what it could have been.

And if he did show up?

Well, that was something else entirely.

“I'll take it from here,” Sister Geneve said, standing up and slipping the envelope into the breast pocket of her pants suit. “Trust in God that what must be, shall be.” She nodded toward Laura and Ronnie on the dance floor. “Now go enjoy the party.”

Spring had come to eastern Ireland at last. Rainy days gave way to hours of flooding sunlight, and purple flowers bloomed along the hills. Wooly new lambs leaped and played in the fields, and pale yellow furze grew heavy over the guardrails of the highways. Sister Geneve had delivered her letter to Eoin at the Quayside after her Sunday bingo night. He hadn't opened it in front of her, so she had no information for Maggie other than to confirm that he had received it. All month, Maggie had wondered why Sister Geneve had offered to help her. She knew that nuns were supposed to be selfless and all, but this wasn't exactly giving alms to the poor: it was aiding and abetting a lovesick teenager. And even though Maggie was grateful for Sister Geneve's kindness, she wondered, didn't that break the rules of nun conduct to go against the orders of one's superior? Didn't they take a vow of obedience? There was only one explanation that made sense: Dan Sean had put her up to it. So on the night before the concert, Maggie went up to visit him and find out.

As she climbed the hill toward Dan Sean's cottage, she stopped to turn her face to the warm sun. The passing of the seasons made her wonder where she would be in a year, in ten years, in twenty years. Would she sit one day at a small stool in the Quayside on Saint Stephen's Day, Eoin older now, maybe with thinning hair or a belly gone soft, touching her gently on the shoulder before he stood to buy her a drink? Or would her life double back to where it had begun, and would she be living in a bungalow in Jefferson

Park or a two-flat in Albany Park, working for the city, married to a cop, watching Bears games on television while outside the air filled with the smell of burning leaves? At Colm's house, Laura had already begun packing boxes. She'd shipped home all of her summer clothes; there was no staying any longer than she needed to. Colm was barely home these days. He drank at the pub, slept on the couch in the sitting room, and puttered in the shed for hours. Once, Maggie had seen him walking down Adelaide Street with a freckle-sprinkled woman dressed in pair of nurse's scrubs. They were laughing together. When he saw Maggie, he stopped laughing.

“It isn't what it looks like,” he'd said. “Your motherâ” he sighed. “Emma, this is Maggie, Laura's daughter.”

“

Oh,

” was all the woman had said.

When she got to the top of the hill she could see through the window the turf fire illuminating Dan Sean, and there was a figure of a woman sitting next to him. A white puff of hair and octagonal glasses. Sister Geneve leaned over to Dan Sean, caressed his face with the back of her white hand. This in itself might not have struck Maggie as terribly odd, but it was the way the nun looked at himâthe same longing look that she'd once seen on her mother's face when Colm came home from work covered in sweat and cement dust; the look that AÃne wore when Paddy recited Tibullus to her under the canvas tent at the Magic Teacups; the look she imagined must have been on her own face when, in the morning of a Dublin hostel, Eoin had said,

I could be the person who won't hurt you.

It was an ageless look, as innocent and hopeful on an old woman as it was on a girl of sixteen. Everyone visited Dan Sean O'Callaghan: it was a duty, a care, an act of respect. But Sister Geneve visited him because she was in love with him.

Maggie remembered the explanation.

I'm not his niece by blood, technically.

Though Maggie had not known it at the time, this had been a justification.

She scrambled behind Billy's shed when she saw the two of them rise from the chairs, and Dan Sean wrapped Sister Geneve's jacket around her shoulders. A few minutes later, the tiny nun emerged from the front door, the old man holding steady to the crook of her elbow. He held on to her as they picked their way down the front path. When they reached her rusty Peugeot, he stopped to lean down and stroke the puffy white hair at the crown of her head. Sister Geneve said something Maggie couldn't catch, and then she reached up to Dan Sean's jowly chin, standing on her tiptoes on the flagstone, drew his face down to hers, and kissed him: a lingering, gentle kiss that flouted and defeated their old age, their frailty, their worn bodies. When they separated and he made his measured progress back up to his front door, Sister Geneve got in her car and looked around her as if reacquainting herself with the trivialities of grass and stones, before starting the ignition and heading down the hill.

Maggie slumped against the shed door.

That's why she gave Eoin the letter. She knows what it's like to love someone when the whole world's against it.

How the town would have loved that scandal: a widower and his dead wife's niece! A niece who also happens to be a nun of the Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary! But then, thought Maggie, what was so ridiculous about that, really? We love who we love. We have as little control over that as we do over anything.

On April 8, the day of the concert, school went by in a torturous blur. Maggie watched the clock until she thought she'd go crazy. At lunchtime, she sat with Nigella and her popular crew, smiled placidly as they one-upped each other with their bawdy talk of blowjobs and nightclubs and clothes. When they finished their sandwiches and Nigella announced they were going out to the chipper to scour for boys, Maggie made a polite excuse that she had to meet Ms. Lawlor to go over a French assignment. Instead, she went into the bathroom stall with her Discman and listened

to

Nevermind

with her eyes closed.

Uncle Kev,

she prayed,

I'm sorry to keep bugging you about this. Just one more reminder: please, please, please, let him be there tonight. It's kind of important.

On the walk home from school, Maggie stopped at a shop and bought herself a ninety-nine, her first of the season. A warm breeze blew from the ocean, and the gulls wheeled and called in the harbor. It really felt like spring. In front of O'Connell's Electronics, a small crowd of longhaired boys with skateboards under their arms had gathered in front of the television sets. Probably some big soccer game, Maggie thought. Or is there a horse race on today? As she walked past them, licking her ice cream cone, she glanced up at the window at the six television screens all programmed to the same channel. She saw six identical images of Kurt Cobain's face: the matted blond hair, the cleft chin, the eyes both mischievous and sad. It was all she'd been thinking about since she'd woken up, and seeing his face on the screens like that was a little bit like wishing for snow and looking up and seeing it fall, beautifully and out of nowhere, from the sky. Then, at the bottom of the screen, she saw the headline:

NIRVANA FRONT MAN KURT COBAIN, 27, FOUND DEAD IN SEATTLE HOME

One of the boys with the skateboards was crying soundlessly. But there were other sounds to occupy the silence: tires on asphalt, women chattering to the babies they pushed in strollers, the deep call, out on the water, of a ship. And the sea, always the sea. Maggie touched the crying boy's arm.

“How?”

“He shot himself.” The boy held out his palm to her, offering a cigarette. The five of them stood there, then, smoking in the bright spring air. Nobody said anything. One by one, the four boys flicked their cigarettes into the street, dropped their skateboards to the pavement, and wheeled away. Maggie had never seen them in Bray before, and after that day she never saw them again. It was

as if they had walked in straight from the water and out again, a band of new wave psychopomps shuttling the souls of the dead across the wide sea line to whatever it was that lay beyond.

Because she didn't know what else to do, Maggie walked home, finishing her cone. She unlocked the door, put her backpack down, and took a shower. When she came out, wrapped in a towel and combing her damp her, Colm called to her from the kitchen.

“Did you hear the news? That Cobain lad is dead.”

“He shot himself,” Ronnie, parked inches from the television, said. “In his greenhouse.”

“Yeah. I heard,” Maggie said numbly. “I can't believe it. Gone too soon. He had his demons, I guess.” The words fell out of her mouth like stones. They meant nothing. Colm stood in the kitchen doorway, his mouth half open, as if to offer some comfort. But the connection with Kevin was so obvious that mentioning it would have been crass. Maggie got dressed and put his letter in her pocket as she always did. She dabbed perfume on her neck and in the crooks of her elbows, where the veins were plump and ready. She moved through the house like a haunted spirit. She surprised herself at how little she wanted to cry.