The Case of the Swirling Killer Tornado (5 page)

Read The Case of the Swirling Killer Tornado Online

Authors: John R. Erickson

Tags: #cowdog, #Hank the Cowdog, #John R. Erickson, #John Erickson, #ranching, #Texas, #dog, #adventure, #mystery, #Hank, #Drover, #Pete, #Sally May

Chapter Eight: A Mysterious Phone Call

I

sniffed the air again, just to be sure.

“Drover, all at once I smell bacon.”

“Yeah, me too. I wonder what it could be.”

“I think it could be bacon, Drover, because bacon smells exactly like bacon.”

“Yeah, I've noticed that too. Funny how that happens.”

“You won't think it's so funny if I find out that you ate my property. Did you just eat some bacon?”

“Well, let's see here. Yes, I did but I'm pretty sure it wasn't yours. It was just lying around under the covers. I don't think it belonged to anybody. It was lost.”

I felt my temper rising. “

It was lost?

What kind of clam-brained answer is that? You knew exactly whose bacon that was and you ate it anyway.”

“Well, I thought . . .”

“You'll pay for this, Drover. If we ever get out of this house alive, you will pay a terrible price for your greed and gluttony and stealing from your very best friend in the whole world. How can you stand yourself?”

“I don't know. I smell pretty bad when I'm wet.”

“That smell comes from your rotten sense of morals, Drover. Who would steal two slices of bacon from his best friend?”

“Well, let's see. Pete would.”

“Yes, of course, but he's a cat. Is that your standard of behavior? Do you want to be a cat when you grow up?”

“Not really.”

“Well, you just might, pal. Were you aware that researchers have found a direct link between bacon and cats?”

“No, I missed that.”

“They've foundâand this is a laboratory test, Drover, solid scientific evidenceâthey've found that dogs who eat two or more slices of bacon often

turn

into cats

.”

“Oh my gosh!”

“And the group with the highest risk included dogs with sawed-off stub tails.”

“Oh my gosh!”

“Yes. You're sorry now, aren't you? Huh? You may have just thrown your whole life away, Drover, and for what?”

“I don't want be a cat. I don't even like cats. I'd hate myself if I turned into a cat.”

“Well, that may be your punishment, son. I'm sorry.”

“You couldn't help it.”

“Thanks. Let's get out of here.”

Little Alfred was already down on the floor and creeping toward the kitchen. I smothered my anger and outrage, hopped off the bed, and followed him through the gloomy darkness.

We sneaked our way through the bedroom and into the kitchen. In the middle of the kitchen, Little Alfred stopped, placed a finger over his lips, and said, “Shhh.”

I don't know why he felt the need to tell us to shush. We were operating in Stealthy Crouch Mode and couldn't have moved any silenter if we'd been flies wearing . . . something. Ballet slippers, I suppose.

But he stopped in the middle of the kitchenâAlfred didâand gave us the shush signal, and then we began the last leg of our dangerous journey to the back door.

We had gone no more than two or three steps when, suddenly and all of a sudden, the creepy dark silence of the night was ripped and torn by the loud ring of a bell.

Holy smokes, we must have tripped a fire alarm . . . burglar alarm . . . air raid siren . . . whatÂever . . . something that made a terrible loud ringing sound. And fellers, you talk about having the liver scared right out of you! That did it.

All at once, we had chaos amongst the yearlings, so to speak. I mean, it was totally dark in there except for the eerie flashes of lightning coming through the windows, and children and dogs were running in all directions.

In the space of ten seconds, I ran into Drover three times. I don't know where he was going. He didn't know where he was going. Running in circles, I suppose.

Then Little Alfred stampeded right over the top of me, stepped on my tail in two places, and went streaking back to his bed.

The Thing, the awful Ringing Thing, rang a second time, sending another jolt of electrical fear down my spine and out to the end of my tail. I had lost all sense of direction. I banged my nose into the kitchen cabinets, slipped and slided on the limoleun floor, and continued to stumble over Drover.

It was then that I began to piece together the pieces of the puzzle. The ringing we had heard, the awful piercing ring that had thrown us into such a panic turned out to be . . .

Hmmm, the telephone, it seemed.

The phone was ringing, don't you see, and that would have been no big deal except for one small detail. Sally May jumped out of bed and came pounding through the house in our direction.

Why? Because the telephone happened to be mounted on the kitchen wall, the east wall to be exact, and since that's where the telephone was ringing . . . you get the point.

Here she came. BAM, BAM, BAM. Those were her footsteps on the floor. As far as I knew, Sally May had a fairly dainty set of hooves, but they sure didn't sound dainty at that hour of the night, when she was chasing the telephone.

Shook the whole house, is what she did, and you can imagine the effect this had on me and Drover . . . mostly Drover. It threw us . . . him . . . into a new and higher dimension of terror.

I mean, from the moment we had set foot in this house, the thing we had feared most was a face-to-face meeting with Sally May.

And now SHE WAS COMING OUR WAY, sounding like thirteen Frankincense Monsters or a herd of charging elephants, and there we were in the middle of her kitchen, running around in circles and banging into things and wondering what form of execution she would choose for us.

Hanging?

Firing squad?

Flogging to death with a broom?

Strangulation?

Perhaps you're wondering why we didn't do the obvious and simple thing, follow Alfred into his room and seek shelter in his closet or beneath his bed.

It wasn't fear of spiders, I can tell you that. The thought of standing before Sally May's frigid glare caused my fear of spiders to melt away like . . . something.

Butter on a piece of corn. A snowflake on a brandÂing iron.

Give me ten thousand crawling spiders and I'll shake all eight hands of all ten thousand if it will spare me the fate of being caught in the house by Sally May.

Trouble was, we couldn't find our way to Alfred's room. I mean, it was very dark in there, and after a guy runs in circles for a while, he loses all sense of direction.

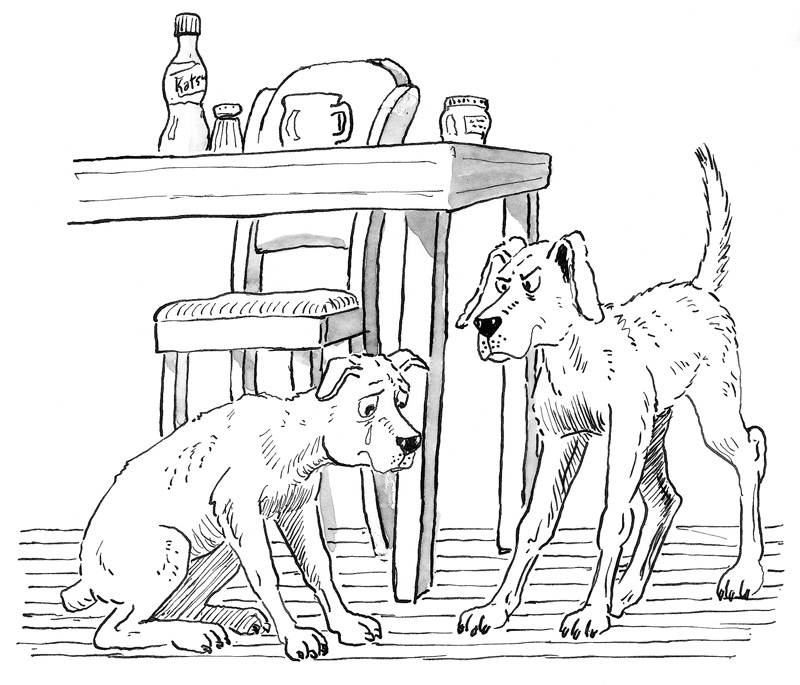

And she was almost there and we were almost dead meat, but at the last possible second, I squirted myself beneath the kitchen table and poured myÂself into a ball in the corner, as far away from her as I could get.

Which wasn't nearly far enough but the best I could do.

Drover followed.

There, we ceased all breathing and waited to see what would happen. Here's what happened.

First, she switched on the lightânot once but several timesâand nothing happened. I mean, no light came on. It appeared that the storm had knocked out the electricity.

Second, the phone continued to ringâa third ring, then a fourthâuntil at last she found the receiver.

Then, in a sleepy voice, she said, “Hello? Who is this? Do you know what time it is? Uh-huh. Then what . . . oh. Ohhhhhh. Oh my goodness. Yes, right away. I hope you'll be all right, and thanks for calling.”

She hung up the phone. By this time, Loper had gotten up and wandered out into the middle of the house, somewhere close to where Sally May was located.

His voice sounded pretty croaky. “Now what? This place is like trying to sleep in downtown Amarillo.”

“That was Slim. He just got a call from the sheriff's office in town. We're under a tornado warning. There's one on the ground and heading our way. Everyone on the creek is supposed to take cover.”

“Wow, that woke me up. Okay, hon, we'd better head for the cellar. You grab Molly and a blanket. Where's the flashlight?”

“In the top drawer, where it's supposed to be.”

Loper's feet shuffled across the kitchen floor. “Dadgum, there's that water again.” He opened the drawer and felt around inside. “Hon, it's gone.”

“It was there just yesterday.”

“It's gone now.”

“I'm not ABOUT to go into that musty cellar without a flashlight. There's no telling what might be down there.”

Just then, guess who came out of his bedroom, walking in the beam of the missing flashlight.

“Hi, Mom. Hi, Dad. Are ya wooking for the fwashwight?”

There was a moment of silence. Then, Loper said, “Why, yes, we were, and one of these days I'd like to hear the story of how you happen to be walking around in the middle of the night with it, but not now.”

Loper took the flashlight and started giving orders. Alfred was to get his blankie and pillow. (In Kid Language, “blankie” means blanket.) Sally May was to gather up Baby Molly while he, Loper, would open several windows and dig a couple of raincoats out of the closet. And everyone was supposed to wear shoes, since they would be walking across weeds and stickers, plus waterdogs, snakes, lizards, and whatever else might be lurking in the darkness.

Moments later, they had all gathered in the kitchen. From my hiding place under the table, I could see their feet and ankles. (The flashlight was on, see.)

Loper spoke in a voice that was soft but firm. “Everybody here? When we get outside, join hands and stay together. Let's go, y'all.”

And with that, they left the house and went out into the stormy night. The last thing I heard before the door closed behind them was Sally May's comment, “What on earth happened to my screen door! Just wait 'til I get hold of those dogs!”

Gulp.

Oh yes, and then Little Alfred whispered, “Bye, doggies. Good wuck.”

Good wuck indeed. We would need several truckÂloads of it.

Chapter Nine: We Hear the Roar of the Hurricane

T

hey were gone. We were left alone in the eerie silence of the house. Off in another room, I could hear a clock ticking.

I hoped it was a clock ticking. If it wasn't a clock, then it was something worse, and right then I didn't want to speculate on what it might be.

I mean, when a guy finds himself alone in a big empty house, he begins to hear odd little sounds and his imagination starts playing tricks on him.

We sure didn't need any of that. Our deal was looking bad enough without any extras.

I moved myself out from under the table, out into the middle of the kitchen floor, and began pacing. My mind seems to work better when I pace. Have I ever mentioned that? Maybe not.

I began pacing. “Well, Drover, this situation has gone from bad to worse. First, we got ourselves lured into the house by a bratty little boy. Then we almost got caught. And now we've been abandoned in the midst of a storm.”

“Yeah, and I'm fixing to turn into a cat!”

I stopped pacing. “What?”

“I'm fixing to turn into a cat. I can feel it happening already, 'cause I feel more like I do right now than I did a while ago.”

“What are you talking about?”

“You said I was going to turn into a cat 'cause I ate your bacon. And I think it's starting to happen.”

“Oh, that. Forget it, Drover, we've got much bigger problems to think about.”

He was starting to cry. “My mom's going to be so disappointed! The last thing she said when I left home was, âDrover, be a good little dog.' She never wanted a cat for a son, and now look what I've done!”

“I tried to warn you.”

“I know you did. You've been a good friend and I wish I'd never tasted raw bacon.”

“Yes, it's almost ruined you. On the other hand, we might try the cure.”

“The cure?” He came padding out from under the table. “You mean . . .”

“Exactly. The same team of brilliant scientists who discovered the link between bacon and CatÂtination, those same guys came up with a cure. Didn't I mention that?”

“No, I didn't know about it.” He began hopping up and down. “Oh Hank, tell me about it, let me be cured. I'll be a good dog for the rest of my life, honest I will!”

“Hmmm.” I paced a few steps away, paused a moment to think, then turned back to Drover. “Okay, I'll do it, just this once and not because you deserve it, because you don't.”

“I know. I was a rat.”

“You really were, Drover.”

“And a pig. I was a terrible pig for hogging all the bacon. I was a pig-hog.”

“You certainly were.”

“But that's all behind me now. No more bacon for me. I'm a changed dog.”

“I'm glad to hear that, son. It renews my hope in . . . you know, we really don't have time to disÂcuss your personal problems.”

“Oh my gosh. What are we going to do?”

“I'm not sure. I was hoping you might have some ideas.”

“Well, let's get me cured, before I turn into a cat.”

“Oh yes, the cure. Here's the deal. Roll over three times and repeat the, uh, curative words. Let's see,

“Piggy bacon, wrongly taken.

Piggy ways are now forsaken.”

“I think I can do it, Hank! Watch this.” He rolled over three times and said the, uh, magic curative words. Then he leaped to his feet and gave himself a shake. “There, I did it and I'm so happy! I don't feel like a cat any more.”

“Great, Drover, I'm happy for you. Oh, one last part of the cure: I get all the supper scraps for a week.”

“Sure, Hank, that's the least I can do.”

He hopped and skipped with joy. I watched him and felt a glow of, well, fatherly pleasure, you might say. Helping others through difficult situations has always . . .

Huh? All at once my thoughts were pulled away from good deeds and helping others, as I suddenly realized that (a) the wind had stopped blowing; (b) the rain had stopped falling; (c) the air seemed thick and heavy.

A spooky calmness had moved through the house, across the ranch, perhaps across the entire world.

“Drover, do you notice anything odd?”

“Well, let's see. We're dogs and we're in the house where the people stay, but all the people went outside where the dogs stay. That seems kind of odd to me.”

“Yes, but I mean the air.”

“Oh.” He sniffed the air. “Yeah, it smells like two wet dogs and I guess that's odd.”

“Wrong again, Drover. All at once the air is still and heavy, and those are symptoms of a hurricane. Are you familiar with hurricanes?”

“I thought they said âtornado.'”

“No, a tornado has never struck this valley. We've already discussed that. It must be a hurricane. Do you know about hurricanes?”

“Well . . . not really.”

“A huge swirling wind, Drover, one of the most destructive storms in all of nature. It can pick up trees, cars, houses, even dogs, and carry them to who-knows-where.”

Lightning twinkled outside and in its spooky silver light I saw Drover's eyes. They had grown to the size of pies.

“Oh my gosh, I had just started feeling safe 'cause Sally May left the house, but now you're telling me . . .”

“I'm telling you that hurricanes are even more dangerous than Sally May when she's mad.”

“Oh my gosh!”

“And we're in grave danger.”

“Oh, this leg is killing me!”

My teeth were beginning to chatter. My legs were quivering. The air was so heavy now, I could hardly breathe. “Drover, we've got to get out of here. But how?”

“Yeah, but how?”

“Good question.”

“Thanks.”

“You're welcome.”

I found myself pacing again, as I tried to focus all my powers of concentration on this problem which seemed to have no solution. I mean, we were locked inside a house, right?

I thought and thought and thought, and also paced and paced and paced. Nothing. It wasn't working.

“Drover, we're cooked.”

“Yeah, and I'm not even hungry.”

I stopped pacing and whirled around to face him. “Yes, because you ate two pieces of my bacon, you little sneak, and . . . why did you mention food? I was talking about something else.”

“Well, I don't know. I guess I'm so scared, I'm liable to say anything. I think you said something about . . . somebody was cooking supper . . . I think.”

“Hmmm. That doesn't ring any bells.”

Suddenly a bell rang . . . the telephone again, perhaps the sheriff's department calling to . . .

Drover jumped. “Oh my gosh, there's one now!”

“Yes, and it's all come back to me. I had just said, âWe're cooked, Drover,' because we are now trapped between Sally May and a deadly swirling hurricane.”

“Oh my gosh, oh my leg, I'm going to jump out a window and get out of here!”

He left the kitchen and went streaking into the living room. “I'm afraid that won't work, Drover. We would be cut to pieces on the glass, so I'd advise you not to . . .”

I heard a thump, then . . . his voice. “I did it, Hank, I made it through the window and now I'm outside!”

I hurried into the living room, toward the sound of his voice. “That's impossible, Drover. I didn't hear the crash of broken glass. You see, windows are made of window glass, therefore . . .”

“Yeah, but the window was open and I knocked the screen off and here I am, outside. Are you proud of me?”

Hmmmm. It appeared that this thing needed, uh, further study. I went streaking to the so-called window and found . . . by George, there was an open window in the living room, and it appeared that someone or something had . . . well, removed the screen, so to speak.

“Okay, Drover, relax. The pieces of the puzzle are falling into place. You're probably wondering why that window happened to be open, aren't you?”

“Not really.”

“I mean, why would anyone open a window in the midst of a rainstorm? Most dogs would never figger that one out, Drover, but I happen to know the answer.”

“You may know the answer but I'm outside the house!”

“Hush, Drover, I'm about to tie this all together. You see, Loper opened several windows. That's what you're supposed to do when a hurricane is coming. Can you tell me why?”

“Hank, these clouds look awful. They're green.”

“Let me finish. When a hurricane is coming, Drover, you open one window to let it in and a second window to let it out. That's why Loper opened the windows, don't you see, and that explains why.”

“Hank, I hear something roaring.”

“Huh? Roaring, you say?”

“Yeah.” We were quiet for a moment, and . . . by George, I seemed to hear a certain . . . well, roaring sound. “Hank, do hurricanes bark or growl?”

“I don't think so. In other words, no.”

“Do they roar?”

That roar was getting LOUDER.

“Drover, we may need to cut this lesson short and . . . yikes, maybe I'd better get out of here!”

And with that, I went flying through the open window.