The Chamber in the Sky (4 page)

Read The Chamber in the Sky Online

Authors: M. T. Anderson

Darlmore led the three of them along a bridge that stuck out of the back of the house and plunged deep into the final tangle of growth that blocked the great valve of the Dry Heart.

Brian could not believe that Thomas Darlmore had given up and hadn't even bothered to check the news of the Game. Darlmore had left the Court because he was outraged, and now, here he was, as lazy as the rest of them. All of those terrifying hours they'd spent creeping through basements, solving riddles, splashing in freezing underground lakes, dodging throwing-stars, and fleeing scent-sensitive ogres â no one had been watching.

Darlmore made Brian almost mad.

It was not far until they reached a kind of boathouse half wedged into the fibers. Inside there was lots of tackle, nets, buoys, sinkers, anchors, and a table with a few candles almost burned down to nothing. The far wall was made of corrugated metal, and a door led through it.

The hermit rattled a key in the door and forced it open. Inside was a tiny space with lots of pleather cushions and bulby windows everywhere. The world outside those windows was black.

Darlmore took down two reels of fishing wire and knotted weird little lures to them. The lures glittered with plastic gems. He didn't talk, but whistled through his teeth.

He ushered the kids into the little dinghy and shut the door behind them. He locked it and shook it to make sure it was firm. He flicked a switch.

Outside the windows, electric lights went on.

They realized that they were in a small pod clamped to the side of the boathouse, which projected out into the stream of the flux â a green fluid that might have been the Great Body's blood. Now that the lights were on, they could see strange, fluttering growths drifting past.

With a tug on a rusty lever, Darlmore set them floating. He revved up a motor â which filled the pod with the smell of water and oil â and puttered out among the groping fronds into the deep green depths.

The reels of fishing line were snapped into slots. Darlmore showed them how to cast. They pressed a little spring-loaded trigger, and watched the line soar off into the drink. They reeled the line in with cranks.

Nothing that they saw looked vaguely like a fish. There were pulpy, tired things, and there were spiky, fast things. There were little golden, flashing things that were too small and fast to catch. They distantly glimpsed a few

huge, blundering things that they were afraid would respond to the lights.

Surprisingly, they had a good time fishing. They called out to one another, and even Brian finally felt part of the action, clapping when Gregory caught something (which turned out to be some kind of bloodweed, but edible) and furiously reeling in a fish-thing of his own.

Gwynyfer had forgotten to dislike the ex-archbishop. She was chattering happily as she thumped a little airlock drawer open to reveal her six-mouthed fish. “Won't this make a delightful supper? We once went fishing down in the Organelles, my mother and father and I. The catch was delish.”

Darlmore clearly was pleased they'd enjoyed the little trip. He turned the boat around and headed back into the looming fronds. He steered them through grottos and around stems until they reached the boathouse. The dinghy attached to the wall with a magnetic

thump

.

They hadn't caught much, but they hoped it would be tasty. Gwynyfer even skipped sideways a few steps along the bridge back to the shack, pulling Gregory by the hand.

Darlmore threw open the door to the kitchen. “One minute. A fire,” he said. “We'll get those stewing. Even the bloodweed.”

Brian went upstairs to look at the Game printouts again. Gwynyfer and Gregory headed into the living room to sit in the hammocks that hung from the massive growth that ran up through the floor and out a hole in the wall

As Gregory swung Gwynyfer back and forth, she sang out, “I had a cousin or second cousin or something who had a tree growing through her living room. Like this. Third cousin, maybe? That branch of the family's very complicated.”

“I have a cousin Prudence who I think you'd like. She's mastered wizardry and sarcasm.”

“Impressive,” said Gwynyfer, who didn't sound particularly happy to be compared with another woman, especially a human one.

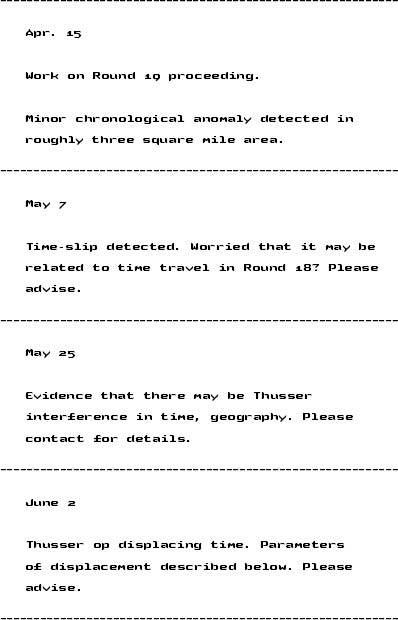

Brian, meanwhile, stood alone, upstairs, scanning the other reports from Wee Sniggleping, the grumpy Norumbegan who'd helped to arrange the Game. The cramped study was getting dark.

The final few pages of the update were awful to read. Back when they'd been on Earth, Brian had seen the problems, the “anomalies,” that the printouts described: The Thusser had built a settlement, altering time itself, subduing humans to act as anchors or mental food for the psychic hunger of their Horde. People were absorbed into their houses and became just another appliance. But all the changes happened gradually, thought quietly became difficult, and no one noticed until it was too late.

Brian hated to read the record of growing panic that Wee Snig had left. The first mention of trouble was from about four months before (as time had once run).

This one was followed by a lot of gibberish with numbers and letters that clearly had some technical meaning Brian couldn't understand.

That was the last transmission received.

Brian could feel the rising panic in Snig's reports. No one had heard his pleas.

Brian thought of Wee Snig and Prudence, waiting for him on the other side of the dark gate between worlds. He hoped they were safe now.

He hoped everyone back in his world was safe.

And then he received a blow to the head.

Thwack!

He reeled â dropped, slammed against the desk.

He half turned.

Then he froze.

Something cold was held against his skull. A gun. And someone said, “Child, don't move. Death is much easier when it's fast.”

T

he hermit made dumplings. He scattered flour on the countertop. Behind him, the bloodweed and meat bobbed in the boiling stew.

As he cooked, Tom Darlmore frowned and wondered what to do. He'd spent a hundred years or more acting as the empire's last ward of the Umpire Capsule, the last courtier to pay attention to the Game. When he was off spelunking in the Volutes, looking for a way out of the Great Body, he'd heard rumors that the capsule still wandered, ready for activation. Farmers saw it stumping along mopily through forests of polyps. Shepherds talked of its mechanical giants lumbering out of the dark and sitting by campfires at night. Darlmore had spent two months tracing the rumors. He'd found the Umpire near South Worthington, just down the road a piece from the town of Mercer's 'testine. He'd considered whether to send it up toward the Dry Heart, but he'd decided against it. The idiots there would just fuss with the thing, break it, destroy it on purpose. There were dukes and duchesses

who wanted to make sure that the Norumbegans never left the Great Body. Back on Earth, they'd been nothing; now they owned a whole kidney or a mine in the tripe. They'd built railroads, vineyards, plantations, castle keeps. They didn't want to lose what they'd gained.

Years. It had been years since he'd cared about the Game. He hadn't noticed when he'd given up. He'd just started to spend his time working on the cabin and nothing else. Repairing the shingles, or dragging great sheets of fiberskin up from the pit below to replace a wall that sagged. He built coops for the branfs, his sluglike feathered pets. The branfs laid eggs. The years went past. A couple times a month, he'd go in to Herm's Depot to sell branf and buy flour, and he'd pick up a postcard from the capsule. But he never wondered much, anymore, about whether he'd ever have to activate the thing and call the Rules Keepers. He just assumed that someday the Great Body would shift or swallow or stretch, and they'd all be engulfed in disaster. That would be it. The end. (He touched his forehead with a floury hand to stave off evil.)

And now these kids. These pawns. Here they were, filled with demands that something had to be done. He remembered when he'd believed that doing things was a good idea.

Maybe he'd go with them. Another voyage. Another adventure. Meet up with the capsule, press the buttons. Feel what it was like again to care about something.

With a new agitation in his fingers, he kneaded the dough.

Then he heard something. Someone was wailing.

Darlmore swiftly and softly walked out of the kitchen, out to the passageway where windows looked down at the path.

Down below: four little creatures milling around the kids' steeds. They were all ridges and blotches and fanned-out crests. Their legs were thin and tiger striped.

They were called imbraxls. They were used, he knew, to stalk prey in the Wildwood.

Two imbraxls sniffed at a steed. One slept. One was bored, and howled for its master.

Someone was here at the shack.

Darlmore stepped back.

Imbraxls would be able to follow attractor juice.

Whoever had crept around the kids' steeds at that inn hadn't necessarily wanted the three dead.

They'd wanted a scent to follow.

Someone had traced the kids here.

Darlmore straightened his back. He returned to the kitchen.

Through the arch, he whispered, “Greg. Gwyn. Brian. Here. Now. No questions.”

But it was too late.

The pistol knocked against Brian's skull.

“Where's the Umpire?” asked the gunman.

Brian protested, “I don't know!” â a little louder than he needed to. He hoped the others could hear that something was wrong.

The gunman's mouth was close to his ear. “Is the archbishop in the kitchen? Whipping up some dish?”

Brian knew the voice. It was Dr. Brundish, a spy for the Thusser who'd fled the palace in the midst of a siege.

Brian asked, “Why do you want him?”

“Where's the Umpire? Is it here in the hut? Does he have it here, child?”

“No it's

not

! It's not here!”

“Then where?”

“We don't know!”

“Quieter. Quieter.”

“How'd you find us?” Brian asked. “How'd you know we were coming here?”

“You spoke many times of wanting to rouse the Rules Keepers. That is the old archbishop's odd hobby, see? I knew that he was somewhere in the Wildwood. So I waited at an inn on the only route into the forest until you arrived, so I could follow you by imbraxl and find him.”

“You know, the stupid juice you painted on our thombulants almost got us killed. It attracted mites.”

Brian felt the man shrug. “Thin you out,” he said. “If I lost one precious child along the way ⦠well, less of the brutal, brutal work of killing left for later.”

At that, Brian flinched.

The doctor jammed the gun harder against his flesh. “Now. Where is the Umpire Capsule?”

“None of us know. What do you want it for?”

“Ready to fall down some stairs?”

A foot slammed into Brian's side and he was hurled

backward, tumbling toward the staircase. He grabbed at the wall, failed, watched his feet trip, but caught himself on the railing just in time. He spun. He was half sitting a few steps down. He crouched, unsure whether he should stand or duck.

Dr. Brundish wheezed and considered. “Interesting. I would have assumed you'd use your elbows more.” Now Brian could see Brundish in full. The Thusser doctor stood above him, dressed in a long coat and dirty robes. His round glasses were pulled up on his pale forehead, and he no longer wore concealing makeup. There were dark rings around his eyes â the mark of the Thusser. His bulky, weird body shifted its mysterious lumps beneath his coat and tunic.

Dr. Brundish took a few steps closer to Brian and whispered, “Let's go meet the others. Will I have the pleasure of finding them with the capsule?”

Brian repeated, “We don't â know â where â it â is.”

“There is an old tradition that a gentleman in your position should put your hands up.”

Brian did. He walked down the stairs with the doctor right behind him.

In the kitchen, they found Gwynyfer and Gregory looking perplexed by the dumplings. Darlmore had just come in the back door from outside and was by the counter.

Everyone was shocked to see Brundish.

“My masters approach from the lower organs,” the doctor said. “The tea dance is over.”

Gwynyfer stepped proudly toward him and said, “The Honorable Miss Gwynyfer Gwarnmore, daughter of the Duke of the Globular Colon, demands â”

“Oh, clap a lock on it, Miss Gwarnmore. A month from now, His Grace your father will be lined up against a wall and shot with the rest of the yawning frat-lads of noble Norumbega. Burned in one big pile, they'll be.” He clicked his tongue. “Down to a frazzle and black char.”

Darlmore's face was as severe as a cliff. He pointed at the door. “Out,” he said.

Dr. Brundish's mouth squirmed in his whiskers. “Archbishop? Yes?”

“Out.”

“I'm looking for the Umpire Capsule. You have it?”

“I don't. Not here. It lives on its own.”

“About where?”

“We don't know.” He glowered at Brundish. “You the Imperial Surgeon?”

“Technically, chirurgeon.” The doctor smiled and sucked his teeth. “Regrettably, I have abandoned my position.”

“I hear my nephew exploded.”

“Quite so. The young are full of such boundless energy.”

“You built him as an implant and a bomb.”

“Don't look at me, Archbishop. The youth was at an awkward age.”

“You detonated the Emperor of the Innards.”

“Not so, Archbishop. Not so. These bad lads stole away my three-way radio. I could detonate no one. It was the

Thusser Magister who hit the trigger. We're in the guts now, you know, the Thusser. The Horde works its way up toward the Dry Heart, even as we speak.”

“What do you want with the Umpire?”

“You know exactly what I want with it, Archbishop. Now where do you have it tucked away?”

“I don't â”

“Tell me, Archbishop.”

Darlmore shook his head. He said, “Defrocked.”

“I recall. Where is it, sir?

Where?

”

Darlmore sneered at the doctor. All look of the hermit in his face dropped away, and he was once again a lord of the Norumbegan Court, brother of the Emperor, scoffing at the ancient enemy of his race.

Dr. Brundish snarled and fired his pistol.

There was a quick blip of light.

Darlmore's leg burst and he fell to the kitchen floor, spattered with his own blood.

Gregory stumbled back in shock, knocking into Gwynyfer. Even she looked frightened, her fairy features wide-eyed and alert.

Thomas Darlmore, once Archbishop of Norumbega, lay rocking in pain near the brick oven, gasping for breath. Blood soaked the leg of his khakis, spreading quickly across his knee.

Brundish reached out with his free hand and grabbed Brian by the hair, dragged the boy close to him, and stuffed the muzzle of his pistol into the boy's ear. “I'm no student of human anatomy,” Dr. Brundish admitted to Darlmore. “The head. Important?”

Darlmore pulled himself up against the pie safe and scrabbled with his knee. “Stop,” he said. “Stop.”

Gregory and Gwynyfer looked wildly from one to the other.

Dr. Brundish sucked in breath through his teeth and blew it out in a whistle. “We need to know where the capsule is. So no one thinks any pretty, pretty thoughts about calling the Rules Keepers.” He yanked on Brian's black hair. “Mr. Darlmore? One more chance.”

Brian winced in pain. His hair was being torn out by its roots. The doctor continued, “How about we play the game this way? Whoever tells me where the capsule is gets to live. As a guarantee. Until I find the capsule. Then you may skip along.” He smiled. His body shrugged its strange mass from side to side. “Anyone? I have plenty of bullets for you all. Who wishes to be the last to live?” He looked from face to face: Gwynyfer's, full of anger. Gregory's, gape-mouthed and confused. Brian's, pale and shivering. And finally, the ex-archbishop on the floor, who had collected himself and now seemed strong and even-tempered.

Thomas Darlmore spoke.

“Let's go,” he said. “Come with me upstairs. I can tell you where the capsule's waiting.”