The Chapel (33 page)

Authors: Michael Downing

Rosalie bent forward, balanced her elbows on her thighs, cradling her head in her hands. She looked ill.

I said a quick prayer on her behalf.

Let it be a stroke.

Andre said, “Now, if you will permit me to move from the sublime to the ridiculous, I have a little cartoon for you.”

A man said, “What is a cartoon?”

Another man said, “Beetle Bailey.”

A woman said, “Charlie Brown.”

The original man said, “Everybody's a comedian.”

“It's a term of art for preliminary drawings,” Andre said. “Giotto drew cartoonsâ

sinopie

âof the entire cycle and its fictive borders and architecture before the final surface for the fresco was applied so his patron could review and approve the work.”

I could hear my own rapid intake of air, little gasps, and so could two of the men in front of me, who repeatedly turned around to register their disapproval for my insistence on breathing.

“Giotto would have made these cartoonsâperfectly delineated and proportioned figures and landscapesâin red ocher, which would be visible when the final layer of fine white plasterâthe

intonaco

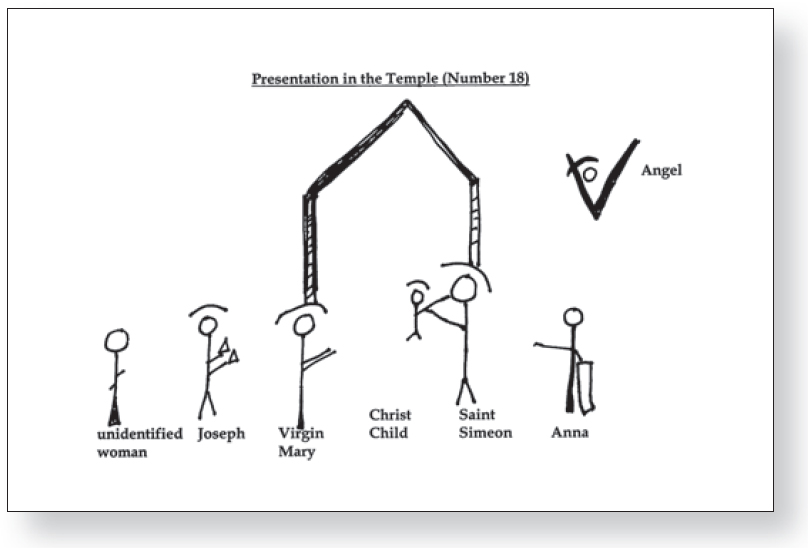

âwas applied to the wall, so it could be seen beneath as the final fresco was painted. I am not an artist, however, and I made you a little stick-figure cartoon.” He handed out two piles for distribution. “I want to use this to prepare you for the other scene we will concentrate on this afternoon, which gives us a clear and simple introduction to the use of color, shape, and geometry in the fresco cycle, and a charming illustration of Giotto's use of space.”

“Oh, man.” One of the men in the front held up the page he'd received and said, “Don't quit your day job.” Laughter spread my way as the pages were passed back.

And just like that, I welled up, tears streaming down my face. At last, my true companion was at hand.

I could fill in the lines, flesh out those people. I knew them well. I recognized every detail except the angel, which I was certain did not appear in the panel painting of this scene, which I had memorized during my many hours on my own in the Gardner Museum while Mitchell pined and pondered over one of Mrs. Gardner's exquisite editions of Dante.

I was here, and I was there. But I wanted to be there and there alone, there in the museum before I knew what it meant to be here. I also wanted the hand of God to reach down through the ceiling and pluck me out of that airless chamber. Short of that miraculous intervention, I did not want to enter the chapel. I didn't want to see the fresco of the Presentationânot with Rosalie, not with Andre and his admirers, not while I was wearing Mitchell's watch.

Andre said, “This is an especially stately painting, with its six human figures aligned in the foreground. Their colorful robes, as you will soon see, bestow on each figure a singularity, a distinct habitable space, and yet the generous folds of those robes overlap, overcoming the space between them, uniting them in spirit. You will see that Giotto painted Jesus as an extraordinarily charming and slightly confounded child, a kid we instantly recognize as a kid. He and Simeon are raised slightly above the others, a status that is here ceremonial and yet also befitting the divine nature of that sweet child.”

He took a pious pauseâhe even bowed his head slightlyâwhich seemed designed to give everyone a chance to contemplate the wonders of the Incarnation and the humility of this shining star of academe. I

didn't doubt his sincerity, but I did wonder if he saw himself reflected in the painted image of Scrovegni, hoisting up the chapel in exchange for a big reward.

“Now, look again at the fullness of time in this image, how Giotto balances the past and future in this moment,” Andre said. “At the far right, Anna, who prophesied the arrival of the Messiah at the temple, is present, holding the scroll of her prophecy. Above her, the Angel of Death is present to confirm that Simeon's death is imminent, fulfilling the promise of the Holy Spirit to the just and devout Simeonâthat he would not die before he met the Messiah. Each figure, in one sense, represents the fulfillment of prophesy, and thus their hands are extended toward each other and toward the child at the center of the frame, the center of all promise, the incarnation of the prophetic word. The Virgin reaches for her son, and at her side, her husband Joseph holds two doves, two earthly creatures that also live in the sky, a kind of mirror of the angel and the Christ child, creatures of this world and not. The woman at the far left of the panel provides symmetry in number, and balance in genderâthree human figures on each side of the picture plane, three male and three female.”

A woman said, “Who is she?”

Andre said, “We don't know.”

A man said, “She looks like a servant.”

But she didn't.

Andre said, “She is dressed in a very remarkable robe for a servant.”

Andre was right. Shelby was clearly a companion to the mother of the Virgin Mary, and her peasant dress marked her as a servant. This pink-robed woman was no one's attendant.

The same man said, “I meant a handmaiden, attending to Mary and her child.”

Andre said, “You will see that both St. Anne and the Virgin often

appear with handmaidens in the frescoes, but this is clearly not either of those women.”

I was already so deeply identified with that woman with no identity that I nearly stood up and announced that I knew her name.

A woman said, “She is not the first woman in history to be treated as if she is insignificant.”

“She is not insignificant. She is unidentified,” Andre said. “Indeed, Ruskin pointed out how beautifully she is drawn, how elegantly her gown is draped and colored. She has an honored place here in the chapel.”

A very elderly woman said, “I'm sure she was happy just to be there.”

It wasn't clear whether that woman was being cynical or sincere, siding with the feminists or with Andre, but most of the women and men in the room nodded their assent. Andre had the wit to let that inscrutable verdict stand, and then the doors behind him slid open and a guard said something rather complicated in Italian before he returned to the hallway behind the doors, where he was hurrying a small group out of the chapel.

Andre said, “There has been a mechanical failure, and the humidity in the chapel has reached a critical level, so I must ask you to reach under your chairs, collect your handouts, and follow me outside.”

A woman said, “Is there a fire?”

A man said, “Nothing works in this country.”

I didn't move until the room was almost empty. I didn't see the hand of God, but this emergency evacuation was an answer to my prayer. I would see the Presentation fresco in my own way, on my own time.

When I finally made it to the edge of the crowd gathered by the benches, Rosalie had disappeared. Andre emerged from the chapel with two men in suits, whispering furiously, and his arrival cleared the benches, so I sat down and scratched. Over the rumbling and

grumbling of the paying customers, Andre said that the guard had informed him that air-quality issues were typically resolved in a few hours, and he assured us that the CPOCH staff had already agreed to give our group additional time in the chapel on Friday.

I had seen enough. I was itchy everywhere, but I decided to wait till I got back to my room and lined up the best of the minibar on the bedside table before I scratched out my eyes.

T

WO HOURS LATER

, I

RAISED MY HAND AND WAVED UNTIL

one of the young white-shirted men weaving through the tables in the Piazza del Something with a tray in his hand nodded. Like Giotto, I was getting good at the language of gestures. I pointed to my empty glass, and about fifteen minutes later, the waiter swooped by with my third Aperol spritz and a fresh bowl of kale crackers. I was sitting at the outer edge of his territory, where I could see the yellow awning on the other side of the crowded piazza. Despite the steady parade of thirsty Paduans shopping for an open cocktail table on their way home from work, I occasionally spotted Matteo's gleaming head under that awning as he nodded at potential customers, whom he greeted as old friends, most of whom he had surely never seen beforeâbusiness as usual.

After a few cool slips, I was near enough to being drunk that it was no longer an effort not to think, so I read the new email from Rachel.

Dearest World Travelerâ

I wanted you to be the first to know: I accepted an offer today. Am feeling dizzy (champagne in the boardroom, and again with David's parents). Maybe I was drunk when I agreed to spend at least one day a week here (and weekends) till I begin, and which I am sure to regret, but the kids will stay at the lake for the summer (happily),

and David (sweetly) agreed to collect a bunch of stuff they can't live without (videogames) and drive it all up in that truck. He is either going to give the food truck a try at the lake this summer (his idea) or (my suggestion) park it in the South Bronx so it is stolen and we can collect on the insurance.

Daddy's gift. What can I say? (The money will come in handy. The boys have decided they want to live at the top of the Empire State Building.) I miss him beyond words. How did he do it on an academic salary? A scholar and a gentleman, that man. I know you must be missing him like mad over there, but I hope you are allowing yourself to have the fun he so wanted you to have. He'd have a ball reviewing the details of my offer, not to mention the reaction from my old boss in Cambridge. I'm rambling. This weekend is looking nutty, so call when you can or I will call you next week (in Rome, I think?) when I know where I am.

The little mess you made by leaking my job news to Davidâlet's just forget it. I have. I forgive you.

Sending love from me and the boys your way.

This all went down rather easily with a couple of sips of the spritz. My second email was from Shelby. As I opened it, the henna-haired woman I'd seen with Ed outside the chapel tapped her knuckles on my table. She was even shorter and rounder than she'd looked at a distance, or else my perspective was less charitable after my last session at the chapel. She was still dressed like a sailor, but instead of Ed on her arm, she was wearing the handle of what looked like a little umbrella on wheels.

She said, “Marimekko.”

I didn't say anything.

She said, “Vintage, yes?”

I said, “It's a relic.” I knew she must be Caroline, Ed's sister, but she seemed so unlikely a wife for T. that I briefly wondered if maybe

she was a nun on vacation. Either way, with that dye job, a veil would have come in handy.

“I saw you earlier today,” she said, “or else there's a '70s revival in this town. I gave away dozens of dresses like yours, and curtains. Are you in the middle of a telephone call? I'm so relieved you're American. When we saw you earlier, I was going to tell you how much I liked your dress, but my brother said you might be Italian. I speak Spanish well enough. Or I used to. I am positively determined to learn some Italian while I'm here. I wish I'd learned more languages when I was young. It's meant to be easier for children for some reason, but I never found Spanish so easy in school. Latinâforget it. My brother knows enough Latin for both of us. He's a priest. Anyway, you finish your call.” She didn't move.

“It's an email,” I said. Now that I was certain she was T.'s ex-wife, I didn't know if I should run away or offer to buy her a drink.

“Go ahead and read it,” she said. “I'd check my email, but I packed away my phone. Mine has a stylus, which is annoying. I should get one like yours. Read, read. I honestly don't mind.”

I really thought she might wander away, so I opened Shelby's email. The subject was “Our Hero, Outside the Uffizi.” There was no text, just a picture.