The Chapel (8 page)

Authors: Michael Downing

Sara never even paused to look at the light. She yelled, “

Pronto!

” and took off across the street like a model down a runway, her green shoes flicking, her tiny hips still, and her ponytail swishing around her swaying shoulders. She was showing off, and she wasn't getting any criticism from the husbands behind her. She never turned around. She raised her long arm and pointed to the right, leading us halfway back to the hotel along a six-foot-high brick wall until she veered off through an open iron gate into a courtyard of paved pathways lined with waist-high brambles bursting with pink roses and the occasional park bench. She opened the door to the visitor center and leaned back to keep it ajar, handing a brochure and

a ticket to each of us as we entered and saying, again and again, “Fifteen minutes to enjoy the wait.”

The room was a big, spare white rectangle, with a long white counter for unticketed visitors to the left, and an open-shelf and tabletop display of scarves and ceramic coasters and postcards to the right. I followed the couples past the gift shop to the coat check, where a sign warned us not to try to carry bags, cameras, food, drink, or pets into the chapel and to switch off our cell phones. I grabbed my glasses and left everything else in the red bag. I was headed back outside to the roses when I spotted Shelby and Anna, seated on a bench on the far side of the room.

Anna waved. She was wearing another handsome knit suit.

Shelby stood up. She was wearing a crinkly white button-up jumpsuit with a pair of camouflage binoculars, big as bazookas, slung around her neck. You had to admire her nerve. When I was still about ten feet away, she hollered, “That shirtdress is killer! You go, girl!”

I said, “You always look ready for anything.” I had left Mitchell's compact black-rubber binoculars at the hotel.

Shelby hugged me and held on long enough to say, “Our friend is a little blue. We took Francesca to the train station this morning.”

“Okay,” I said. When she let go, I bent to kiss Anna, as if she were my aunt, and then sat down between them.

Sara was standing right in the middle of the room, leaning into her big leather purse, her jacket and white shirt pulled up, exposing a few inches of her tiny waist.

Anna said, “God forgive me, I'm grateful my husband isn't here to see that.”

The four live husbands had staked out spaces at the front of the line by the door to the chapel. Their wives were wending their way past the other ticketed visitors, holding their opera glasses overhead as if they were swimming upstream.

Shelby stood up and said, “Shall we dance?”

I stood up.

Anna said, “Where are we going now?”

“We're halfway there,” Shelby said. “We have to be dehumidified. Apparently, we go from here to a special air-conditioned room and watch a video about Giotto for fifteen minutes, and then we have our fifteen minutes in the chapel.”

Anna said, “Only fifteen minutes?”

I said, “Andy Warhol meets Giotto.”

Anna said, “When I came here as a girl, none of this museum business existed.”

Shelby said, “Did you come to Mass here?”

“Oh, no. I don't think it was ever used like that. It was just a place my mother loved.

La mia piccola cappella

.” She stood up, but her mood was sinking. “She wouldn't recognize it now.”

As we joined the line, Shelby said, “We're so lucky to be alive and here today. It's only a few years ago that they finally finished the restoration. Imagineâthe frescoes could have just peeled and flaked and faded away.”

Anna said, “In Florida, there's black mold on everything.”

The line snaked out through the door, along a paved path, which dipped as it neared the unadorned side of the little dusty brick chapel on our left. A vast woodland park spread out to the right with walking trails twisting around massive black boulders and disappearing into the glimmering greenery. The line stalled outside a dark glass vestibule, a kind of modern greenhouse attached to the chapel. From some angles, you could see the people inside, seated on folding chairs, watching a TV monitor while they were dried out.

Someone well ahead of us said, “Three minutes.”

Anna said, “Now what are we waiting for?”

Shelby said, “There's another group of twenty-five ahead of us.”

Anna didn't seem to approve of the glass vestibule or the wait.

I asked if she wanted to sit on one of the nearby benches.

She said, “I just hope it still feels like her little chapel.”

We heard a woman yell, and the whole crowd turned to see Sara streaming down the path like one of the Furies trying to catch up with her crazy sisters, holding some sort of baton in her right hand. She came to a teetering halt next to Shelby. Instinctively, the whole crowd closed in. Sara bent over to catch her breath, and when she straightened up, she yelled, “

Attenzione! Attenzione!

”

“That goes without saying,” I whispered to Shelby, a little too loudly. I got several approving nods from the women on the periphery.

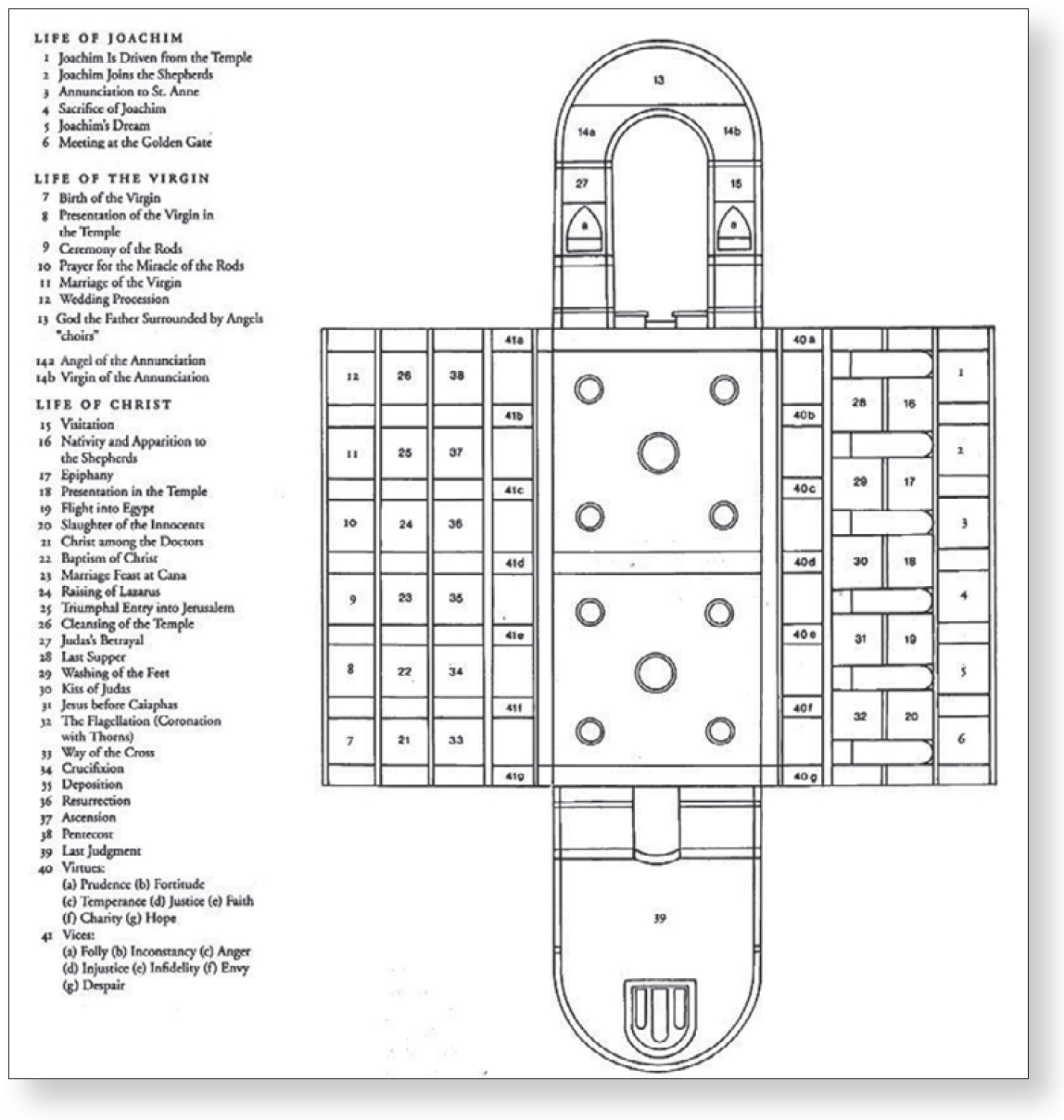

Sara slid a rubber band from her baton and peeled off a single sheet and handed it to Anna. “My EurWay guests only and not the others did not yet receive these helpful maps I am now passing to them,” Sara said breathlessly. She was already starting to move away from us. “These are perfect preparation for the chapel.”

Shelby grabbed several sheets as Sara passed and handed two to me.

Anna looked at the diagram and said, “This can't be right. Did they make it bigger inside?”

Shelby said, “It's not a floor plan. It's flattened out. It's a guide to the frescoes on all four walls and the ceiling.”

The door to the vestibule opened, and the three of us slid into one of the open rows near the back. I watched the tour group ahead of us filing into the chapel through a glass breezeway at the other end of the room. Another group was filing out of the chapel down a ramp behind them. They were there, we were here, and there was already another group congregating outside, and twenty-five more tourists picking up their tickets behind them. All the coming and going made my time in the chapel seem both precious and pointless. Several people in our group were unhappy with their seats and kept popping up and scanning the room, as if they belonged in first class. Shelby was busily tearing and folding her diagram. Anna looked lost.

As the lights dimmed, Shelby passed Anna the fragile paper box she'd made by crudely tearing Sara's handout along the perimeter of the diagram and folding up the four numbered panels. She had turned the map into a diorama.

Anna looked inside the box. “That's it. That's her chapel.”

The video crackled and popped on the TV screen at the front of the room, and a vaguely medieval melody drifted back toward us.

Apologetically, Shelby whispered, “But the ceiling is on the floor.”

Anna whispered. “We'll stand on our heads.”

B

LUE

.

Had Mitchell been standing beside me, where he belonged, he would have whispered, “First impression?”

My first and enduring impression of the chapel was blue.

The ceiling was a deep azure evening sky flecked with golden stars. The residents of the heavens were provided with golden portholes on either end, and from the smaller of these windows on the world bearded saints and patriarchs looked down approvingly. The bigger, central lookout above the altar end was occupied by Jesus in his middle age, and near the original entrance, above the Last Judgment, the Virgin Mary held her infant son for all to see.

But wherever I looked, no matter which sainted gaze held mine, I felt the pulsing of that beautiful blue, not watery but viscous, as if all of us, the living and the dead, were swimming in that intergalactic amniotic fluid.

Blue was my first impression every time I turned and looked to the top of another wall, the blueness of sky above and beyond the figures in each frame of the painted story circling around above us.

This blueness was not constant. It faded from top to bottom, the sky in each succeeding row of pictures a little paler, each sequential layer of the story a little less saturated with the immensity and depth of eternity.

Eventually, I had to give my neck a rest. Staring straight ahead, I ran my gaze along the row of pale greenish-gray panels at eye level, the Seven Vices on one side, the Seven Virtues on the other,

rendered not in lifelike hues but colorless, pallid, like stolid marble statues of themselves.

Second impression?

Had one of the strangers wandering around me asked, I would have said my second impression of the chapel was the crazy smile on the white snout end of the big gray equine head of a donkey. He was giving Mary and Jesus a ride, but that didn't really account for the smirk.

My third impression was that T. had drawn the chapel perfectly. It was just one big barrel vault. There was a sanctuary with an altar embedded at one end, a window at the top of the other end, and six big windows cut into one side. And that was it for structural detail. The restânot just the human figures and the landscapes, but what I had first seen as supporting columns and arches, elaborate pilasters and medallions carved in relief, and even the beveled and chamfered frame around every separate frescoed sceneâwas an illusion. The gloriously illuminated and architecturally complicated chapel was not really there. There was nothing but paint painstakingly applied to the smooth plaster walls of a brick-and-mortar barrel vault.

The pleasure of this masterful illusion was complicated by my turning and turning and not seeing Mitchell. If I stood still, I could almost conjure his voice, but it was mixed up with the baritone narration that had accompanied the introductory video we'd watched. I closed my eyes to concentrate, but everything was jumbled up, a stew of half-remembered facts and speculation from which I plucked a pet confusion of mine about Dante and this chapel, which Mitchell always called Scrovegni's chapel. He'd meant this as censure, not praise.

As far as I knew, Dante had never seen this chapel. And yet in Dante's visionary poem, Scrovegni had been singled out and labeled as an unredeemable scoundrel. I never understood, despite Mitchell's many little lectures, why Dante had picked on Scrovegni,

made his name infamous by identifying him alone among the crowd of otherwise anonymous moneylenders suffering in the Seventh Circle of his Inferno.

According to the video, both Reginaldo Scrovegni and his son Enrico figured in the history of the chapel. Reginaldo had been infamous, one of the most ruthless and successful moneylenders of the 13th century. But Dante never met him, and there were plenty of rich usurers in Florence, whom Dante would have known personally and despised. Reginaldo was dead by 1300, when his son Enrico paid to have this chapel built and then decorated and offered up to the Virgin Mary.

The dedication of the chapelâEnrico's flamboyant act of contrition for the sins of his fatherâwas memorialized by Giotto in the Last Judgment, the huge fresco Number 39 on Sara's map. In the bottom left quadrant, Giotto painted Enrico and a priest hoisting the chapel building up to the Virgin Mary. This exchange was taking place while Jesus, high above them, was separating the haloed and pious figures from the eternally damned, several of whom were serving as snacks for a giant horned ogre with a potbelly.

According to Giotto's painting, Enrico and his chapel were firmly fixed on the side of the saved. Yet Dante's poem had relegated the Scrovegnis to the deepest-down depths of hell.

Giotto and Dante were contemporaries, and I knew they were both alive in 1300, but when I tried to recall who did what whenâwell, I couldn't remember my children's birthdays, never mind the speculative and often wildly revised estimates for the completion of a pre-Renaissance painting or a poem. Mitchell had shown me reproductions of Giotto's Last Judgment many times, tracing his finger through the layered lines of saints and sinners to demonstrate the painter's debt to Dante's spiraling circles of hell. Mitchell believed that Giotto had been compelled to paint Enrico and his chapel into

the scene because Scrovegni and everyone else in Italy had read

The Inferno

and Scrovegni wanted a happier ending for himself and his family name. This all made sense and, as was so often true of my conversations with Mitchell, did not really address my question. Why did Dante pick on Scrovegni, of all people?