The China Factory (19 page)

Authors: Mary Costello

âAye, Alice, things have changed. If things were different⦠Aye⦠It's not the same at all today. The young are right nowâthey do what they like. They don't care what anyone else thinks, and they're right too⦠They'll have no regrets then.'

She is standing in the dark of the kitchen, her handbag dangling from her arm. A light is blinking out on the bay and down below her is a land full of dark shapes. Her heart is racing. She would like to stand at the shore and look into the ocean's depths and let the waves break over her bare feet and watch them turn and flow back

out, to break on other shores. She thinks of her life, her whole existence, as a catastrophe. She drops her arm and the bag slides off and she thinks how everything has sprung from one moment, one deedâthe insane beauty and shock of the flesh, the fire of the soulâwith consequences that flowed out and touched and ruptured every minute and hour and day of her life ever since. That brought her to her own crime, her own awful act, on a Belfast street, the

relinquishment

. Greater than all that had gone before or would ever come after. Making her heart grow small, making extinct everything that was essential for a life. Was it all fated, she wonders? Was the desire fated? And the shame? And the crimeâwas the crime fated, too?

In the bedroom she switches on the lamp and sits on the edge of the bed. She searches for a word but there is none capable of containing what she feels. She narrows her eyes and a procession of words crosses her mind, like ticker tape, and then she feels its approach, the only word that is ample; it rises out of her in a voice she has never heard in these rooms, an exhalation, an utterance, a cry.

John

.

Tears fall on her hands. She hears the faint hiss of the lamp. She looks around at the walls. Eventually her heartbeat slows. There is no repose, there will be no repose, just the long wait in these rooms, and the sea sighing in the distance.

The author is grateful to the Arts Council of Ireland for its generous support.

READ ON FOR AN EXTRACT FROM

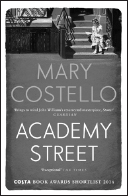

AS HEARD ON BBC RADIO 4 BOOK AT BEDTIME WINNER OF THE IRISH BOOK AWARDS NOVEL OF THE YEAR 2014 SHORTLISTED FOR THE COSTA FIRST NOVEL AWARD 2014

Tess Lohan appears to be a quiet child. But within lies a heart of fire. A fire that will propel her from her native Ireland into the hurly-burly of 1960s New York. In this city she will face the twists of a life graced with great beauty, but forever floating close to hazard. Joyous and heart-breaking,

Academy Street

journeys through six decades and one incredible story.

âExceptional'

The Times

âPacked with emotional intensity'

Sunday Times

âWith extraordinary devotion, Mary Costello brings to life a woman who would otherwise have faded into oblivion' J.M. Coetzee

âI read this book from cover to cover in one night, unable to stop' Maggie O'Farrell

âA powerful and emotional novel from one of literature's finest new voices' John Boyne

âBrings to mind John Williams's resurrected masterpiece,

Stoner' Guardian

£8.99 ISBN 978 1 78211 420 8

£8.49 EBOOK ISBN 978 1 7821 1419 2

1

IT IS EVENING and the window is open a little. There are voices in the hall, footsteps running up and down the stairs, then along the back corridor towards the kitchen. Now and then Tess hears the crunch of gravel outside, the sound of a bell as a bicycle is laid against the wall. Earlier a car drove up the avenue, into the yard, and horses and traps too, the horses whinnying as they were pulled up. She is sitting on the dining-room floor in her good dress and shoes. The sun is streaming in through the tall windows, the light falling on the floor, the sofa, the marble hearth. She holds her face up to feel its warmth.

For two days people have been coming and going and now there is something near. She wishes everyone would go home and let the house be quiet again. The summer is gone. Every day the leaves fall off the trees and blow down the avenue. She thinks of them blowing into the courtyard, past the coach house, under the stone arch. In the morning she had gone out to the orchard and stood inside the high wall.

It was cold then. The pear tree stood alone. She walked under the apple trees. She picked up a rotten yellow apple and, when she smelled it, it reminded her of the apple room and the apples laid out on newspapers on the floor, turning yellow.

She lies back on the rug and looks up at the pictures on the wallpaper. Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Her mother told her the story. She picks out the colours â dark green, blue, red â and follows the ivy trailing all over the wallpaper, all around Adam and Eve. They are both naked except for a few leaves. Eve has a frightened look on her face. She has just spotted the serpent. A serpent is a snake, her mother said. The apple tree behind Eve is old and bent, like the ones in the orchard.

She feels something in the room. A whishing sound, and a little breeze rushes past her. She sits up, blinks. A blackbird has flown into the room. It flies around and around and she smiles, amazed, and opens her arms for it to come to her. It perches on the top of the china cabinet and watches her with one eye. Then it takes off again and comes to rest on the wooden pelmet above the curtains. It starts to peck at a spot on the wall. She holds her breath. She listens to the tap-tap of its beak, then a faint tearing sound and a little strip of wallpaper comes away and the bird with the little strip like a twig in its beak rises and circles and flies out the window. She looks after it, astonished.

The door opens and the head of her sister Claire appears. âIs this where you are?

Tess!

Come on, hurry on!'

Something is about to happen. Her older sisters Evelyn

and Claire are home from boarding school. She loves Claire almost as much as her mother, or Captain the dog. More than she loves Evelyn, or Maeve her other sister, or even the baby. Equal to how she loves Mike Connolly, the workman.

The door opens again, and Claire holds out her hand urgently for Tess to come. There are people standing around the hall, waiting. The front door is wide open and outside there are more people. She can hear their feet crunching the gravel and the hum of low talk. She looks around at the faces of her aunts and cousins, her neighbours. Her teacher Mrs Snee is smiling at her. Claire pulls her close â they are standing next to Aunt Maud now â and squeezes her hand and bows her head. Suddenly she is frightened.

A shuffle on the upstairs landing and everyone goes quiet. Men's voices, half whispering but urgent, drift down from above. She thinks there must be a lot of people up there but when she looks up there are only shadows and shoulders beyond the banisters. She sighs. She will soon need to go to the bathroom. She looks down at her new shoes. She got them in Briggs' shop in the town during the school holidays, along with the green dress she is wearing. Her mother got new shoes that day too. And a new blue dress. Her mother bent down to tie her laces and Tess left her hand on her mother's head, on the soft hair.

The stairs sweep up and turn to the right and it is here on the turn, by the stained-glass window, that her uncle's back comes into view. Light is streaming in. Her heart starts to beat fast. She sees the back of a neighbour, Tommy Burns, and her other uncle, struggling. And then she understands.

At the exact moment she sees the coffin, she understands. It turns the corner and the sun hits it. The sun flows all over the coffin, turning the wood yellow and red and orange like the window, lighting it up, making it beautiful. The gold handles are shining. It is so beautiful, her heart swells and floods with the light. She closes her eyes. She can feel her mother near. Her mother is reaching out a hand, smiling at her. She can feel the touch of her mother's fingers on her face. Her mother is all hers â her face, her long hair, her mouth, they are all hers. Then someone coughs and she opens her eyes.

The men are almost at the bottom of the stairs and the coffin is tilted, heavy. She is afraid it will fall. Her father and her older brother Denis get behind it now, lifting, helping. She looks down, presses her toes against the soles of her shoes to keep her feet still. She wants to run up the last few steps and open the coffin and bring her mother out. She looks at the handles again, and at the little crosses on the top. She tries to count them. There is a big gold cross on the lid. Last night, when her cousin Kathleen took her up to bed, they passed her mother's room. The shutters were closed and candles were lit. There were people standing and sitting and leaning against the walls, neighbours, relations, all saying the Rosary. She dipped her head to see past the crowd. She could not see her mother. Just the dark wood of the wardrobe and the wash stand. And the mirror covered with a black cloth. And leaning up against the wall, against the pink roses of the wallpaper, the wooden lid with the gold cross, and the light of the candles dancing on it. They

put the lid on over her mother. She looks up at Claire, about to speak, but Claire says âShh', and tightens her grip on Tess's hand. A silence falls on the hall. She turns and sees the big brass gong that she and Maeve play with sometimes by the wall. She wants to reach for the beater and hit the gong hard.

The coffin is crawling towards the front door. Then the men leave it down on two chairs, and rest for a minute. When they pick it up again everyone walks behind it and it passes through the open door, into the sun. On the gravel there is a black hearse and a thousand faces looking at them. The men bring the coffin to the back of the hearse and shove it in through the open door, like into a mouth. Maeve starts to cry and Claire goes to her.

Tess turns and sees Mike Connolly at the edge of the yard, with Captain the dog at his feet. He is holding his cap in his hand. She thinks he is crying. Everyone is crying, but she is not. She looks up and sees the blackbird on the laurel tree, eyeing her.

You robber

, she wants to shout,

you tore my mother's wallpaper, and now she's dead

. She looks past the white railings that run around the lawn, over the sloping fields and the quarry, far off to a clump of trees. Then the hearse door is shut and she gets a jolt. She looks around. She does not know what to do. The evening sun is blinding her. It is shining on everything, too bright, on the laurel tree and the lawn and the white railings, on the hearse and the gravel and the blackbird.

The hearse pulls away and people start walking behind it. Her uncle's car follows and then the horses and traps, and the neighbours, wheeling bicycles. Claire is beside her

again, leaning into her face. âYou've to go into the house, Tess. You and Maeve, ye're to stay at home with Kathleen.'

Her cousin Kathleen takes her hand, leads herself and Maeve around to the side of the house, down the steps into the small yard. Before they reach the back door, Tess breaks away and runs back across the gravel, the lawn, off into the fields. On a small hill she stands and watches the hearse moving up the avenue, turning onto the main road. It moves along the stone wall that circles her father's land, the crowd and the horses and traps walking after it. Sometimes the trees or the wall block her view. But she watches, and waits, until the black roof of the hearse comes into view again, flashing in the sun. It slows and turns left onto Chapel Road, and the people follow, like dark shapes. Then they begin to disappear.

She stands still, watching until the last shape fades and she is alone. She is gone. Her mother is gone. She feels a little sick, dizzy from the huge sky above. She feels the ground falling away from under her â the grass and the field and the hill are all sliding away, until she is left high and dry on the top of a bare hill. Like the Blessed Virgin in the picture in the church when she is taken up into Heaven from the top of a mountain. Maybe she, Tess, is being taken up into Heaven this very minute. She can hardly breathe. She turns her face towards the low sun and closes her eyes and waits.

Please

. She waits for her mother's face to appear, a hand to reach out. She leans her whole body upwards, desperate for the sun to touch her, the wind to raise her, the sky to open, Heaven to pull her in.

When she opens her eyes she is still in her father's field, and there, a few feet away, are cattle, five or six, staring at her with big faces and sad eyes. The ground is under her feet again, the grass is green, nothing has changed. She looks around, frightened, ashamed. She starts running back towards the house. She runs into the yard, searches the barn, the coach house, the stables. She sticks her head into the dark musty potato house and calls out, âMike, Mike, are you there?' and waits and listens. Everywhere is silent. Soon it will be dark. She hears the sound of a motor in the distance. A car is coming down the avenue. She stands and waits for it to appear in the yard. Her heart is pounding. It is the hearse, she thinks, returning. With her mother sitting up in the front seat, smiling, and the coffin behind open, empty â a terrible mistake put right. They had come to the wrong house. They had come for the wrong woman â it was old Mrs Geraghty back in the village they should have taken.