The Circle (30 page)

Authors: Mats Sara B.,Strandberg Elfgren

No one says anything.

‘Your powers are a wonderful gift,’ the principal continues, ‘but they can also be very dangerous to yourselves and to others. Your abilities are in their infancy, but as they develop, you’ll find it harder to control them.’

She turns to Vanessa. ‘One day you’ll make yourself invisible and discover you can’t reverse the process. You might be forced to spend the rest of your life as a shadow.’

Abruptly Vanessa stops chewing her gum.

That must be the worst nightmare for someone who’s so much in love with her own reflection, Minoo thinks.

‘The same goes for the rest of you,’ the principal says. She lets her gaze linger on Anna-Karin, before she moves on to Ida, Minoo and Linnéa. ‘Even those of you who have not yet developed any powers.’

Perhaps Minoo should feel frightened, but that ‘yet’ has made her happy. Perhaps she has a power after all. The principal seems to think so.

‘There has always been a certain amount of magic in the world. And the barriers separating our world from others has varied in strength over time.’

‘What “other worlds”?’ Vanessa interrupts.

‘Our world isn’t the only one. There are countless others. Don’t interrupt me again,’ the principal says sternly. ‘During the last few centuries we’ve lived through a magical drought with occasional local flare-ups. One such flare-up took place here about three hundred years ago. Your dreams might be channelling what happened then.’

‘How do you know what we’ve been dreaming?’ Vanessa asks.

‘My raven saw and heard everything that was said on the night of your awakening. It’s the opinion of the Council and myself that the one who spoke through Ida that night was the Chosen One from the 1600s.’

‘Who was she?’ Minoo asks. ‘And what happened to her?’

‘We don’t know. The church and vicarage burned down in 1675, and a great many important documents were lost.’ The principal regards them gravely. ‘If I compared the last two thousand years to a magical drought, then what’s coming is more like a flood. Individuals with powers like yours have been incredibly rare, but now they’re appearing in a number of places across the world. The battle that is coming may affect our entire reality.’

‘That’s why Nicolaus spoke of our destiny,’ Anna-Karin says.

Adriana purses her lips. ‘I’d prefer to call it your task,’ she says.

‘So you mean that the fate of the world will be decided in Engelsfors?’ Vanessa asks.

‘I know it’s hard to imagine,’ the principal says, with a hint of a smile, ‘but that may well be so. This place has a high level of magical activity, which will continue to grow.’

Minoo listens, fascinated. ‘So magic doesn’t exist everywhere?’

‘No.’ The principal looks at Minoo approvingly, as if she thought it was a good question. ‘We believe that the energy will eventually spread over ever larger areas, but just now we’re looking at local phenomena.’

Vanessa says thoughtfully. ‘Does that mean our powers won’t work everywhere? For instance, if I went to Ibiza on holiday, could I become invisible there?’

‘Ibiza, as it happens, has a very high level of magical activity,’ the principal answers, ‘but you’ve understood correctly. The power doesn’t just come from within you. You have to be hooked up, as it were, to a power source. And that’s here. You need Engelsfors, just as you need each other, and Engelsfors needs you. We still don’t know why there were … seven of you. But together you form a circle. Witches have worked in circles throughout the ages. You won’t get anything important done if you don’t learn to work together.’

She’s wrong to reduce it to a ‘task’, Minoo thinks. ‘Destiny’ is a much better word.

Rebecka had understood that. This is much bigger than they are and they are destined to carry it out. But in any case they are tied to Engelsfors. And to each other.

‘Any more questions?’ the principal asks.

Everyone remains quiet.

She smiles, satisfied. ‘Right,’ she says. ‘Let’s talk about magic. Theory and practice.’

31

‘FORGET EVERYTHING YOU

think you know about magic and the supernatural,’ says Miss Lopez. ‘I guarantee it’s wrong. We make sure of that.’

‘How?’ Linnéa asks.

‘Among other things, the Council has a special department that goes through whatever information is on the Net. There may be kernels of truth in what you find there. Some magical facts are hidden in folklore and traditions, but they’re so inextricably intertwined with nonsense that it’s virtually impossible to distinguish one from the other. We remove anything that gets too close to the truth, and leave all the misleading junk. The lunatics and amateurs actually do us a big favour.’

‘So you’re engaged in censorship as well?’ Linnéa says contemptuously.

‘We’re entering a new magical age so we have to be in control of whatever knowledge there is. You can’t imagine what damage it could cause if it were to fall into the wrong hands.’

But Linnéa won’t back down. ‘And who decides whether

it

’s in the wrong hands? You and the Council? Who keeps an eye on

you

?’

The principal smiles mirthlessly. ‘

Quis custodiet ipsos custodes

? “Who protects us from our protectors?” The ancient philosophers asked that question, and I’m not going to discuss it right now.’

Minoo looks pleadingly at Linnéa and gets a grimace in return. She longs for order, not more chaos.

The principal opens her bag. She hands out five identical black books and silver loupes. Minoo weighs her book in her hand. It’s incredibly heavy for something so small. She examines the loupe. It’s segmented into eight parts of which six are very thin, ribbed and adjustable.

‘This is the

Book of Patterns

,’ the principal says. ‘And this’ – she holds up a loupe – ‘is one of two tools at your disposal for interpreting it. This is the other,’ she says, and taps her temple.

Vanessa groans.

‘Open your books,’ the principal says.

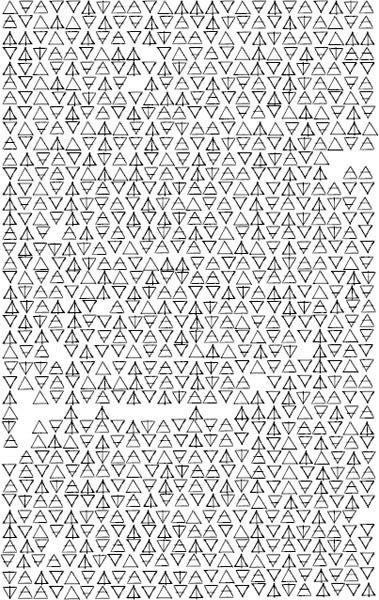

Minoo opens hers. Six symbols are lined up on the first page.

She turns it. Then another and yet another.

‘I don’t see any patterns,’ Ida says. It’s the first thing she’s said all morning.

Minoo doesn’t say so, but she agrees with Ida. The pages are covered with incomprehensible symbols of various sizes. Some may look as if they’re in some kind of order, but others are scattered everywhere. Some pages are blank. It looks like the most difficult IQ test ever, and Minoo is stumped.

‘Six symbols,’ the principal says, ‘arranged in magical constellations. You can only learn what they mean through deep and sustained reflection and with the help of this.’

She holds up the loupe again. ‘The Pattern Finder.’

‘What’s in this book anyway?’ Anna-Karin asks.

‘That depends on who’s looking,’ the principal responds. ‘No two witches see the same thing. The

Book of Patterns

acts as transmitter and receiver. The witch reading it has to know what she’s looking for. Then the book will show her what she needs. It’s like tuning into the right frequency on an old-fashioned radio.’

‘And the thing you use to tune in with is … that?’ Ida asks.

‘Yes. But it’s useless if your senses aren’t focused on the search.’ The principal’s eyes are dreamy. ‘The book often knows what we need better than we do. It’s as if it can see right into our souls.’

‘Cheesy,’ Vanessa says in a sing-song voice.

The principal glares at Vanessa. ‘On the contrary,’ she says. ‘This book contains all the knowledge that a witch will ever need. What you see depends in part on how well

developed

your powers are, and in part on what symbol you belong to. It contains magic formulae and rites, prophecies and tales from the past.’

‘Does that mean our prophecy looks like this?’ Linnéa says, and points at a page on which the symbols look as if a tornado has passed through the book.

Adriana Lopez nods. ‘That’s why it’s not easy just to read out the prophecy to you. When the time is right, you’ll be able to see it, but you won’t all see it in the same way.’

‘Then how do

you

know what’s in it?’ Minoo asks. ‘If everyone sees different things, I mean.’

‘Generations of witches have read the prophecy and written down exactly what they’ve seen. The texts overlap at a number of points. It’s a question of pure statistics.’

‘So the majority is always right?’ Linnéa asks.

‘I see you’re the philosopher here,’ the principal answers mordantly.