The City of Dreaming Books (13 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

Also sitting in the café was another inhabitant of Lindworm Castle, Pentametros Rhymefisher, a former classmate of mine. I informed him of Dancelot’s death and he expressed his sympathy. When I told him what a lousy dump my hotel was, he gave me the address of another, assuring me that it was well kept and inexpensive. We wished each other a good trip and went our separate ways.

A little while later I found the recommended hotel in a narrow side street. Some Norselanders were just emerging from it. They looked well rested and in good spirits. If those fastidious, law-abiding and reputedly tight-fisted individuals favoured this establishment, I told myself, it really must be clean and cheap - quiet too, in all probability, because no Norselander would shrink from summoning the forces of law and order if someone disturbed his night’s rest.

I asked to be shown a room. It proved to be completely bat-free, the water in the washbasin was clear as glass, the towels and bedlinen were clean, and no disturbing noises were issuing from the adjacent rooms, just the subdued voices of some civilised fellow guests. I booked the room for a week and had a really thorough wash for the first time since my arrival in the city. Then, refreshed and filled with curiosity, I set off on my next excursion.

B

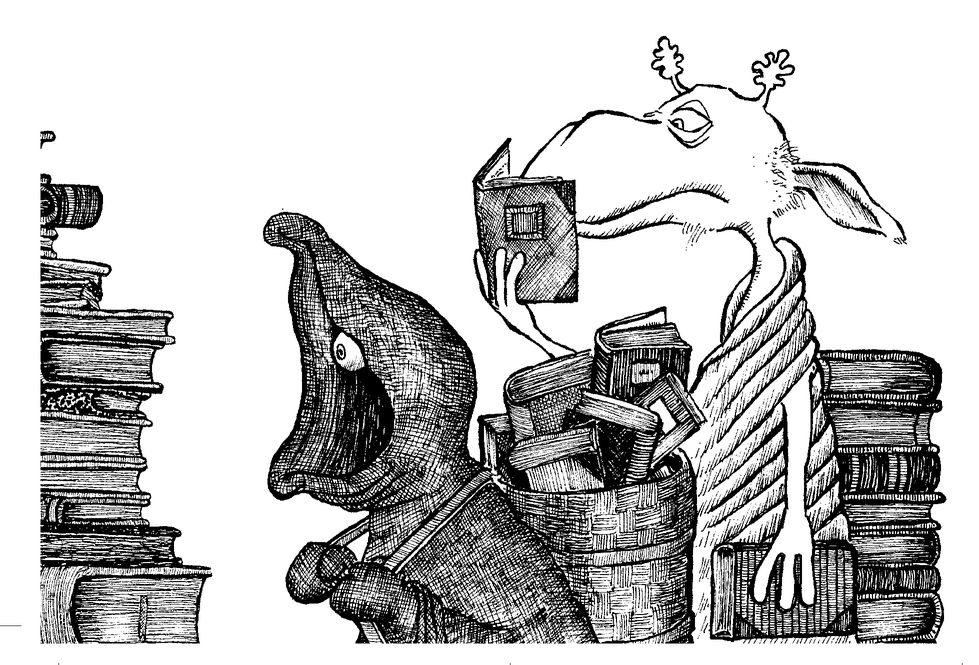

ooks, books, books, books. Old books, new books, expensive books, cheap books, books in shop windows or bookcases, in sacks or on handcarts, in random heaps or neatly arrayed behind glass. Books in precarious, tottering piles, books parcelled up with string (‘Try your luck - buy our surprise package!’), books displayed on marble pillars or locked away behind grilles in dark wooden cabinets (‘Signed first editions - don’t touch!’). Books bound in leather or linen, hide or silk, books with clasps of copper or iron, silver or gold - even, in one or two shop windows, books studded all over with diamonds.

ooks, books, books, books. Old books, new books, expensive books, cheap books, books in shop windows or bookcases, in sacks or on handcarts, in random heaps or neatly arrayed behind glass. Books in precarious, tottering piles, books parcelled up with string (‘Try your luck - buy our surprise package!’), books displayed on marble pillars or locked away behind grilles in dark wooden cabinets (‘Signed first editions - don’t touch!’). Books bound in leather or linen, hide or silk, books with clasps of copper or iron, silver or gold - even, in one or two shop windows, books studded all over with diamonds.

There were adventure stories supplied with cloths for mopping your brow, thrillers containing pressed leaves of soothing valerian to be sniffed when the suspense became too great, and books with stout locks sealed by the Atlantean censorship authorities (‘Sale permitted, reading prohibited!’). One shop sold nothing but ‘half’ works that broke off in the middle because their authors had died while writing them; another specialised in novels whose protagonists were insects. I also saw a Wolperting shop that sold nothing but books on chess and another patronised exclusively by dwarfs with blond beards, all of whom wore eye-shades.

The big bookstores did not specialise, however, and usually displayed their wares in no kind of order - a system clearly favoured by their customers, as one could tell from the gusto with which they rooted around in them. There were no bargains to be had at the specialist bookshops, so it was almost impossible to find a well-known author’s signed first edition at a reasonable price. The surprise packages on offer at the big antiquarian bookshops, on the other hand, might well contain a volume worth many times the rest of the package put together, and anyone who ventured downstairs into the basement of one of these huge establishments dramatically increased his chances of discovering some item of real value.

An unwritten rule prevailed in Bookholm: ‘The price pencilled inside the cover is valid, and that’s that!’ In view of the vast numbers of old volumes transported into the city every day, it was inevitable that dealers and their assistants were often too pressed for time to assess the true value of items while sorting through them. Indeed, they were sometimes so harassed that they didn’t even look at them, just sold off whole crates and sacks at knockdown prices. The result was that valuable books, too, came on the market and were wrongly classified, then banished to dark cellars or buried under stacks of cheap trash. They fell behind bookcases, slumbered in boxes under faded publishers’ lists or languished on high, inaccessible shelves and were nibbled by rats and woodworms. These treasures were the main reason why Bookholm exerted such an attraction. The tourists who visited it were amateur Bookhunters, so to speak. Anyone could strike gold if only he looked for long enough.

Most visitors were collared on arrival by tourist guides who steered them into huge bookstores displaying stacks of largely worthless rubbish. The staff made a practice of mingling a few little gems with the cheap stuff, however, so a lucky tourist could make the occasional discovery even there. When he brandished the book in triumph and loudly rejoiced at the ludicrous price inside the cover, that was the most effective advertisement of all. Word that someone had paid a few measly pyras for a first edition of Monken Maksud’s

Beacon in the Gloaming

would spread like wildfire and the shop would be besieged all night long by customers in search of similar lucky finds.

Beacon in the Gloaming

would spread like wildfire and the shop would be besieged all night long by customers in search of similar lucky finds.

The bookstores that catered for a mass clientele had either bricked up their entrances to the catacombs or concealed them behind bookcases to prevent their customers from straying inside. Only a few streets away from the big bookstores and cheap cafés, however, things became more interesting. The shops were smaller and more specialised, their shopfronts more artistic and individual, their wares older and more expensive. They also granted access to certain areas of the catacombs -

certain

areas, mark you, because they allowed their customers to descend only a few storeys, after which the entrances were bricked up or sealed off in some other way. It was quite possible to get lost in these subterranean passages for several hours, but everyone found their way out in the end.

certain

areas, mark you, because they allowed their customers to descend only a few storeys, after which the entrances were bricked up or sealed off in some other way. It was quite possible to get lost in these subterranean passages for several hours, but everyone found their way out in the end.

The further into the city you went, the older and more dilapidated the buildings, the smaller the shops and the fewer the tourists became. In order to enter some of these antiquarian bookshops you had to ring a bell or knock. From them you could

really

descend into the catacombs without restriction but at your own risk. If the customer was a new and unknown Bookhunter the staff would issue exhaustive warnings, informing him of the dangers and drawing attention to the fact that torches, oil lamps, provisions, maps and weapons were on sale in the shop, as well as balls of stout string for attaching to hooks on the premises - a device that enabled you to venture into the depths in relative safety. Other bookshops offered the services of trained apprentices who were well acquainted with certain parts of the catacombs and would take you on guided tours.

really

descend into the catacombs without restriction but at your own risk. If the customer was a new and unknown Bookhunter the staff would issue exhaustive warnings, informing him of the dangers and drawing attention to the fact that torches, oil lamps, provisions, maps and weapons were on sale in the shop, as well as balls of stout string for attaching to hooks on the premises - a device that enabled you to venture into the depths in relative safety. Other bookshops offered the services of trained apprentices who were well acquainted with certain parts of the catacombs and would take you on guided tours.

I had learnt all these things from Regenschein’s book, so my knowledge of them made those inconspicuous little shops seem to me like doorways into a mysterious world. For the moment, however, I was uninterested in leaving the surface of the city. I was engaged on a very special mission: bound for Pfistomel Smyke’s antiquarian bookshop at 333 Darkman Street.

I came to a spacious square - an unusual sight after all those narrow lanes and alleyways. What struck me as more unusual still was that it was unpaved and dotted with gaping holes among which tourists were strolling. It wasn’t until I saw that these pits were inhabited that the truth finally dawned: this was the celebrated or notorious

Graveyard of Forgotten Writers

!

Graveyard of Forgotten Writers

!

Such was the popular name for it, its official, more prosaic appellation being Pit Plaza. It was one of the city’s less agreeable sights and one of which Dancelot had always spoken in hushed tones. It wasn’t a genuine graveyard, of course. No one was buried there - or not, at least, in the conventional sense. The pits were occupied by writers too impoverished to afford a roof over their heads. They wrote to order for any tourist willing to toss them some small change.

I shivered. The pits really did look like freshly dug graves, and vegetating in each of them was a failed writer. Their occupants wore grimy, tattered clothes or were swathed in old blankets, and they wrote on the backs of used envelopes. The pits were their dwellings, a few tarpaulins being their only makeshift protection at night or when it rained. They had reached the bottom of the professional ladder, the very lowest point to which any Zamonian author could sink and the nightmare that haunted every member of the literary fraternity.

‘My brother’s a blacksmith,’ a tourist called down into one of the pits. ‘Write me something about horseshoes.’

‘My wife’s name is Grella,’ called another. ‘A poem for Grella, please!’

‘Hey, poet!’ yelled a Bluddum. ‘Write me a rhyme!’

I quickened my step and hurried across the square. Aware that many a writer with a brilliant past had been stranded there, I did my utmost not to look down, but it was almost impossible. I glanced to left and right. Smirking youngsters were scattering sand on the poor fellows’ heads. A tipsy tourist had tumbled into one of the holes and was being helped out by his friends, who were roaring with laughter. Meanwhile, a dog was cocking its leg on the edge of the pit. Its occupant, who took no notice of these goings-on, continued to jot down a poem on a scrap of cardboard.

And then the worst happened: I recognised a member of my own kind! Languishing in one of the graves was Ovidios Versewhetter, a boyhood idol of mine. I had sat at his feet during his well-attended readings in Lindworm Castle. Later he had left to become a famous big-city writer, but little had been heard of him thereafter.

Versewhetter had just composed a sonnet for some tourists and was now reciting it in a hoarse voice. They giggled and tossed him a few coppers, whereupon he thanked them effusively, baring his neglected teeth. Then, catching sight of me, he likewise recognised one of his own kind and his eyes filled with tears.

I turned away and fled from the appalling place. How terrible to have sunk so low! In our profession we were always threatened with an uncertain future - success and failure were two sides of the same coin. I strode off - no, I broke into a run - and left the Graveyard of Forgotten Writers behind me as quickly as possible.

When I finally came to a halt I was in a seedy little side street. I had evidently left the tourist quarter, because there wasn’t a single bookshop in sight, just a row of shabby, ramshackle buildings with the most noxious smells issuing from them and muffled figures lounging in the doorways.

One of these hissed an invitation as I went by: ‘Hey, want someone panned?’

Oh, my goodness, I’d strayed into

Poison Alley

! This was no tourist attraction; it was one of the places in Bookholm to be shunned on principle by anyone with a vestige of common sense and decency. Poison Alley, the notorious haunt of reviewers who plied for hire! Here dwelt the true dregs of Bookholm, the self-appointed literary critics who wrote vitriolic reviews for money. This was where anyone unscrupulous enough to employ such methods could hire venomous hacks and unleash them on fellow writers he disliked. They would then pursue his

bêtes noires

until their careers and reputations were utterly ruined.

Poison Alley

! This was no tourist attraction; it was one of the places in Bookholm to be shunned on principle by anyone with a vestige of common sense and decency. Poison Alley, the notorious haunt of reviewers who plied for hire! Here dwelt the true dregs of Bookholm, the self-appointed literary critics who wrote vitriolic reviews for money. This was where anyone unscrupulous enough to employ such methods could hire venomous hacks and unleash them on fellow writers he disliked. They would then pursue his

bêtes noires

until their careers and reputations were utterly ruined.

‘Sure you don’t want a thorough hatchet job?’ the hack whispered.

‘No thanks!’ I retorted. I only just resisted the urge to fly at his throat, but I couldn’t refrain from passing a remark. I came to a halt.

‘You guttersnipe!’ I snarled. ‘How dare you drag the work of honest writers in the mire where you yourself belong?’

Other books

The Seal of Oblivion by Dae, Holly

Head in the Clouds by Karen Witemeyer

Journey to Bliss (Saskatchewan Saga Book #3) by Ruth Glover

Blackcollar: The Judas Solution by Timothy Zahn

Bookends by Liz Curtis Higgs

You Suck by Christopher Moore

Kentucky Traveler by Ricky Skaggs

The Black Mass of Brother Springer by Willeford, Charles

Shooting for the Stars by Sarina Bowen

Shadow War by Sean McFate