The City of Dreaming Books (9 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

One particular type of adventurers - they were known as Bookhunters - had specialised in running these precious works to earth in the bowels of Bookholm and bringing them to the surface. Many Bookhunters were hired by collectors or dealers, others went prospecting on their own account. The sums offered for volumes on the Golden List were so astronomical that a single specimen could make a Bookhunter wealthy for life.

It was a dangerous occupation - the most dangerous in all Bookholm. You, my courageous readers, may conceive of going in search of some book as an antiquarian’s boring spare-time hobby, but here in the depths of this mysterious city it was more perilous than hunting Crystalloscorpions in the glass grottoes of Demon Range. Why? Because the catacombs of Bookholm teemed with dangers of a very special kind.

The labyrinthine tunnels were said to be connected to

Netherworld

, the mysterious Realm of Evil reputed to extend beneath the whole of Zamonia. According to Colophonius Regenschein, however, the dangers lurking in the darkness below the city were real and lethal enough to be able to dispense with the support of old wives’ tales.

Netherworld

, the mysterious Realm of Evil reputed to extend beneath the whole of Zamonia. According to Colophonius Regenschein, however, the dangers lurking in the darkness below the city were real and lethal enough to be able to dispense with the support of old wives’ tales.

It is impossible to ascertain precisely when the very first Bookhunters descended into the darkness, but the assumption is that it must have been roughly when professional antiquarianism first became established in the city. Bookholm had been the centre of the Zamonian book trade for many hundreds - indeed, thousands - of years: from the time when the first handwritten volumes appeared to the present age of mass production.

It was discovered at a very early stage that the catacombs’ dry atmosphere rendered them ideal places in which to store paper. Whole national libraries were deposited in them. This was where princes hid their literary treasures, book pirates their booty, dealers their first editions and publishers their stocks.

Bookholm wasn’t really a city at first. It existed almost entirely below ground in the form of inhabited caves linked ever more closely by artificial tunnels, shafts, galleries and stairways, and occupied by tribes and communities of the most diverse life forms. All that existed on the surface were the mouths of the caves and a few huts. From these the city continued to develop above ground until it attained its present size.

There was a wild and anarchic period in Bookholm’s history, a time devoid of law and order during which raids and forays, mayhem, murder and thoroughgoing wars were of daily occurrence below ground. The catacombs were ruled by warlike princes and ruthless book pirates who fought to the death and were forever wresting literary treasures away from each other. Books were carried off and concealed in the ground, whole collections deliberately buried by their owners to hide them from the pirates. Wealthy dealers had themselves mummified after death and entombed with their literary gems. There were one or two valuable books for the sake of which whole sections of the catacombs were converted into death traps with converging walls, spear-lined pitfalls and spring-operated blades capable of transfixing or beheading incautious thieves. Intruders who activated a tripwire might instantly flood a tunnel with water or acid, or be crushed to death by falling beams. Other tunnels were purposely infested with dangerous insects and animals that bred unchecked, rendering the catacombs more hazardous still. The Bookemists, a secret society of antiquarians with alchemistic tendencies, celebrated their grisly rites down below. It was believed that the so-called

Hazardous Books

originated during this lawless period.

Hazardous Books

originated during this lawless period.

All of the catacombs’ rational inhabitants were driven from them by the epidemics and natural disasters, earthquakes and subterranean volcanic eruptions that followed, and only the toughest and most stubborn remained behind.

This marked the true beginning of civilised life in the city and the birth of Bookholm’s professional antiquarianism. Many treasures were brought to the surface, bookshops and dwellings arose, guilds were founded, laws enacted, crimes proscribed and taxes raised. Some of the entrances to the subterranean world were built over and others bricked up; those that remained were sealed off with doors and manhole covers, and rigorously guarded. From then on, only those parts of the catacombs that had been surveyed, mapped and pronounced safe could be entered, and then only by dealers who had obtained licences granting them access to the areas in question. They were entitled to exploit licensed tunnels and sell any books they found there. They were also at liberty to explore deeper levels, but it was not long before none of them ventured to do so after the boldest of their number had either returned more dead than alive or failed to return at all. This was how the first Bookhunters appeared on the scene.

They were audacious adventurers who had been commissioned by dealers or collectors to find rare books for them. Although no Golden List existed at this time, legends arose concerning very rare items. The Bookhunters began by looking for scarce and valuable works at random, often proceeding on the simple assumption that a book was older and more valuable the deeper it was located. Most of them were uncouth, insensitive souls, ex-mercenaries or criminals with little knowledge of literature and antiquarianism - in fact, some couldn’t even read. Their principal qualification was an absence of fear.

Then as now, the Bookhunter’s trade was governed by a few simple laws. Since those who had entered the catacombs could never be certain whether or where they would emerge, the following rule applied: the bookseller via whose premises Bookhunters regained the surface was entitled to sell their haul and retain ten per cent of the proceeds. Another ten per cent went to the Zamonian exchequer and the lion’s share to the Bookhunters themselves. It was, however, an open secret that they also used other, illegal routes - sewers, ventilation shafts or tunnels of their own - and sold their booty on the black market.

As time went by the Bookhunters developed various methods of finding their way back to the surface. They marked bookshelves with chalk, unreeled balls of twine behind them or laid trails of confetti, rice, glass beads or pebbles. They drew primitive maps and illuminated many stretches of tunnel with lamps in which phosphorescent jellyfish were immersed in nutrient fluid. They staked out their territories, hewed springs of drinking water out of the living rock and established supply depots. It might be said that, in their own modest way, they brought a touch of civilisation to the catacombs of Bookholm.

For all that, bookhunting remained a hazardous form of livelihood. Successive generations of Bookhunters had to conquer new areas of the catacombs, and the deeper they went the greater the dangers became. Their work was made no easier by hitherto unknown life forms, huge insects, winged bloodsuckers, volcanic worms, fanged beetles and poisonous snakes. But every Bookhunter’s most dangerous foe continued to be his own kind.

The rarer the really valuable books became, the fiercer the competition for them. Where Bookhunters had once been able to help themselves to a superabundance of literary treasures, several of them would now go hunting for the same long-lost library or the same rare item on the Golden List. This often triggered a cut-throat contest of which there could be only one winner. The catacombs of Bookholm were strewn with the skeletons of Bookhunters with axes embedded in their bleached skulls. The more refined manners became in the city overhead, the cruder and more brutal they became in the world beneath. In the end a permanent state of war prevailed there - a lawless, merciless conflict of each against all. Taron Trekko could not have chosen a less favourable moment to assume the professional name Colophonius Regenschein and become a Bookhunter.

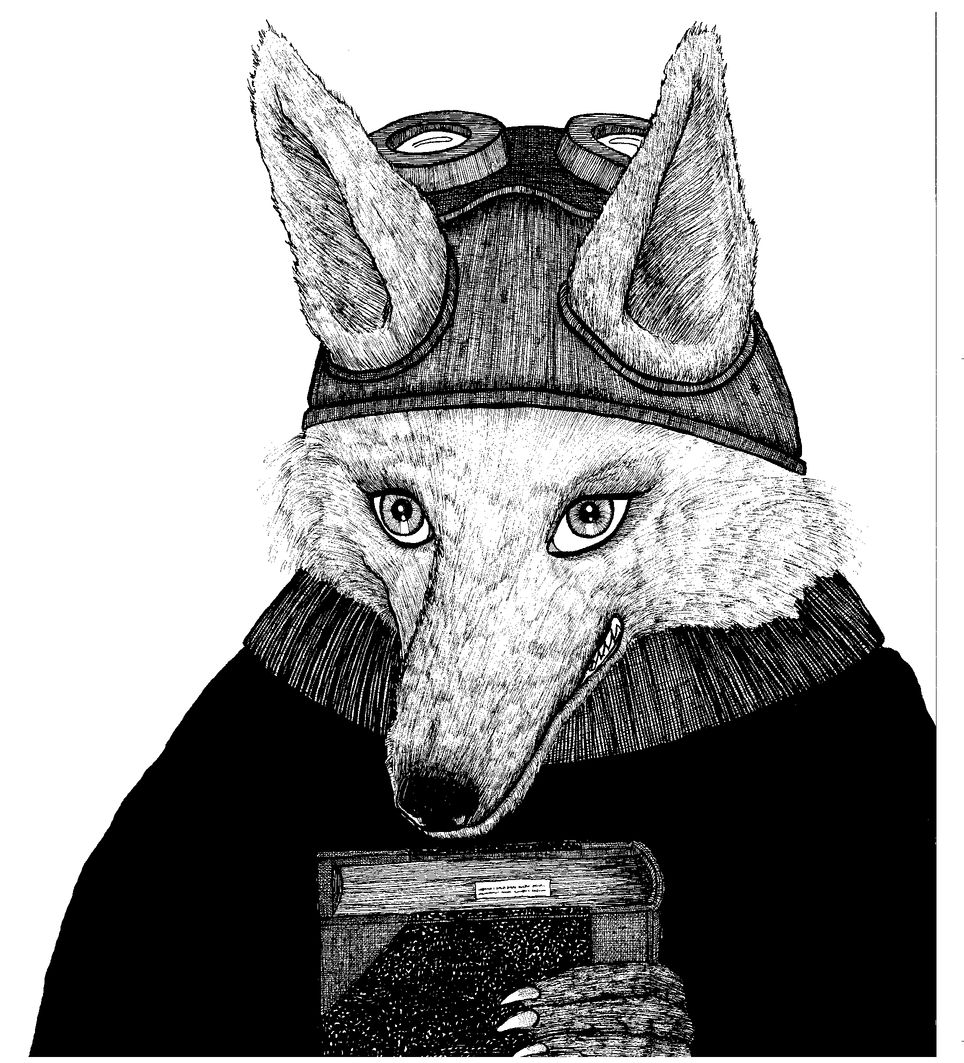

He was, in fact, the first of his kind to become one. Being a Vulphead, he was positively predestined for that profession. Vulpheads are tough and in prime physical condition. They possess excellent powers of recall, an above-average sense of direction and a wealth of imagination. Most Bookhunters were distinguished by their fearlessness and brutality alone, whereas Regenschein brought a new attribute into play: his intelligence. He found it harder than they did to master his fears, was not as strong and ruthless, and did not possess the same criminal energy. But he did have a well-laid plan and was determined to become the most successful Bookhunter of all time. In this respect his phenomenal memory would prove to be his most important asset.

While still living on charity (and, as he himself confessed, on petty theft and stolen food), he acquired the knowledge he deemed indispensable to his aims by spending long hours in the municipal library and numerous bookshops. He learnt dozens of ancient languages, memorised old maps of Bookholm’s underworld and combined the information he gleaned into a grand plan of action.

He studied the history of book manufacture from the handwritten manuscript to the modern printed volume and found temporary employment at a printing works and a paper mill. He learnt to distinguish between different papers and inks blindfolded, so as to be able to identify them by touch and smell in total darkness. He attended lectures on geology, archaeology and mining at Bookholm University, studied books on subterranean flora and fauna and made a note of which of the catacombs’ plants, fungi, sponges, reptiles and insects were edible and which poisonous, which harmless and which dangerous. He learnt how to stave off starvation for days by chewing certain roots, how to recognise the most nutritious species of worms and catch them, and how to detect veins of drinking water in the rock by means of geological features.

Next, Regenschein became apprenticed to one of Bookholm’s ex-libris perfumers. This was a profession unique to the city. For hundreds of years, wealthy collectors had made a practice of impregnating their books with perfumes manufactured to order. This lent their treasures an olfactory stamp of ownership, an aromatic ex-libris that was not only detectable and unmistakable, even in the dark, but invaluable to anyone concealing his books beneath the surface.

Colophonius Regenschein was equipped with a good sense of smell. Although Vulpheads’ noses are not as sensitive as those of Wolpertings, or even of dogs, because their canine instincts and faculties have atrophied over the generations, they can nonetheless recognise olfactory nuances undetectable by other Zamonian life forms. Regenschein sniffed his way through the whole library of scents belonging to Olfactorio de Papyros, an ex-libris perfumer whose family business had helped to endow legendary collections and rare volumes with their unique fragrances for many generations. He memorised the books’ titles and their authors’ names, the details of where and when they had disappeared, and any other particulars about them he could find. He sniffed leather and paper, linen and pasteboard, and learnt how these different materials reacted to being steeped in lemon juice, rosewater and hundreds of other aromatic essences.

The

Smoked Cookbooks

published by the Saffron Press, the balm-scented manuscripts of the naturopath Dr Greenfinger, the

Pine-Needle Pamphlets

of the Foliar Period, Prince Zaan of Florinth’s autobiography (rubbed with almond kernels), the

Rickshaw Demons’ Curry Book

, the ethereal library of mad Prince Oggnagogg - Colophonius Regenschein became acquainted with every book perfume ever made. He learnt that books could smell of soil, snow, tomatoes, seaweed, fish, cinnamon, honey, wet fur, dried grass and charred wood, and he also learnt how these odours could change over the centuries, mingling with the aromas of the catacombs to such an extent that they often underwent a complete transformation.

Smoked Cookbooks

published by the Saffron Press, the balm-scented manuscripts of the naturopath Dr Greenfinger, the

Pine-Needle Pamphlets

of the Foliar Period, Prince Zaan of Florinth’s autobiography (rubbed with almond kernels), the

Rickshaw Demons’ Curry Book

, the ethereal library of mad Prince Oggnagogg - Colophonius Regenschein became acquainted with every book perfume ever made. He learnt that books could smell of soil, snow, tomatoes, seaweed, fish, cinnamon, honey, wet fur, dried grass and charred wood, and he also learnt how these odours could change over the centuries, mingling with the aromas of the catacombs to such an extent that they often underwent a complete transformation.

In addition to this, of course, Regenschein studied Zamonian literature. He read everything that came his way, whether novel, poem or essay, play script, biography or collection of letters. He became a walking encyclopaedia. Every last corner of his memory was crammed with texts and particulars relating to Zamonian creative writing and the life and works of the most varied authors.

Colophonius Regenschein trained his body as well as his mind. He developed a breathing technique that enabled him to survive even in the most airless conditions. He also went on a slimming diet that reduced his weight sufficiently for him to squeeze through the narrowest of passages and fissures in the rock. In the end, when he felt thoroughly qualified to embark on a career as a Bookhunter, he decided to do so with a bang that would be heard all over Bookholm.

He did not choose any old bookshop for his first excursion, nor did he set off on an aimless quest. No, he turned his expedition into a venture that evoked scornful accusations of megalomania from everyone in the city. Through the medium of the Live Newspapers he announced exactly when and where he would descend into the catacombs and when and where he would reappear on the surface. He also gave advance notice of the three books he intended to unearth:

Princess Daintyhoof

, the only surviving signed first edition of Hermo Phink’s legendary account of how the Wolpertings originated, bound in Nurn leaves;

, the only surviving signed first edition of Hermo Phink’s legendary account of how the Wolpertings originated, bound in Nurn leaves;

Other books

Fatal Fixer-Upper by Jennie Bentley

The Marine's Naughty Sister by Terry Towers

Take What You Want by Jeanette Grey

The Art of Not Breathing by Sarah Alexander

A Very Menage Christmas by Jennifer Kacey

Not My Will and The Light in My Window by Francena H. Arnold

The Three by Sarah Lotz

Time Fries! by Fay Jacobs

Jack of Clubs by Barbara Metzger

A Secret Love by Stephanie Laurens