The City of Dreaming Books (33 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

‘They serve to deter unwelcome visitors,’ Al explained, ‘should any find their way here. Actually, no one has ever entered our territory who wasn’t a Bookling. With two exceptions. You’re the second.’

I was still busy digesting his reference to teleportation, quite apart from feeling as if I’d just been abruptly roused from a deep sleep, so neither this last remark nor the sight of the sculptures made any great impression on me. I tottered after the trio in silence.

As we passed through the gateway all my drowsiness left me in a flash. Ahead of us lay a plateau from which a wide stone staircase led down into a vast stalactite cave. Al paused, threw out his arms and cleared his throat. ‘Behold,’ he cried,

‘This fortress built by Booklings for themselves against Bookhunters and the hand of war! ’

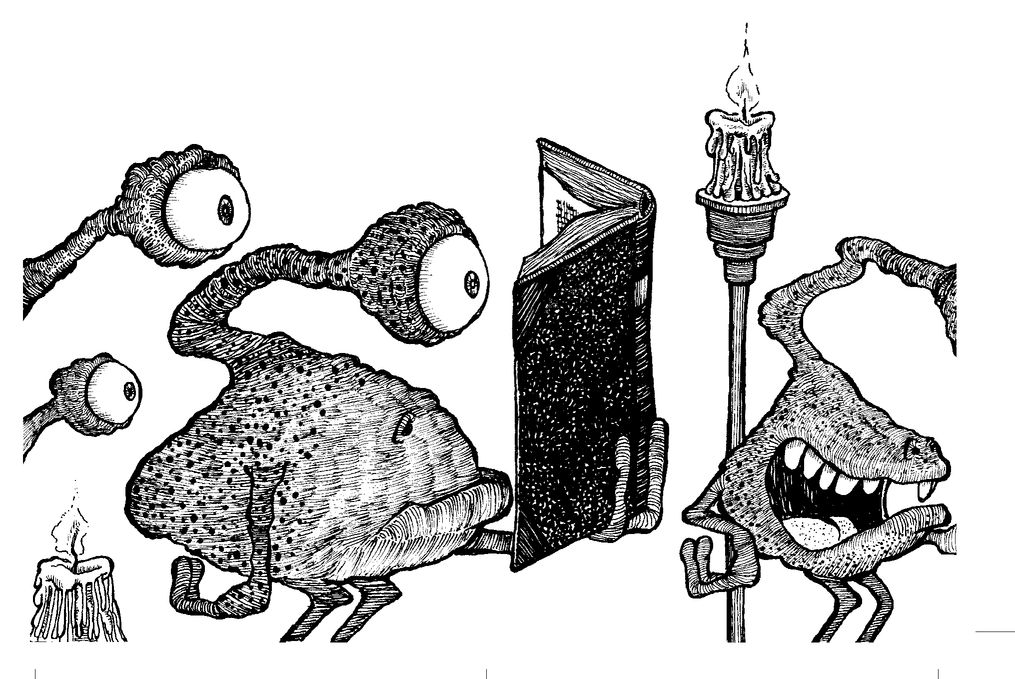

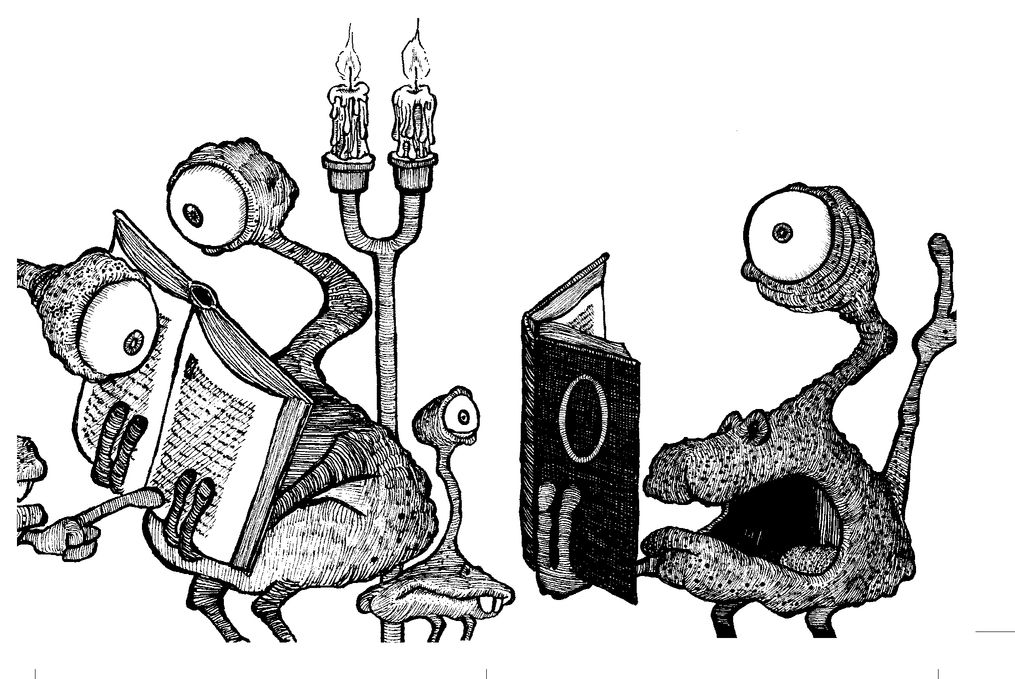

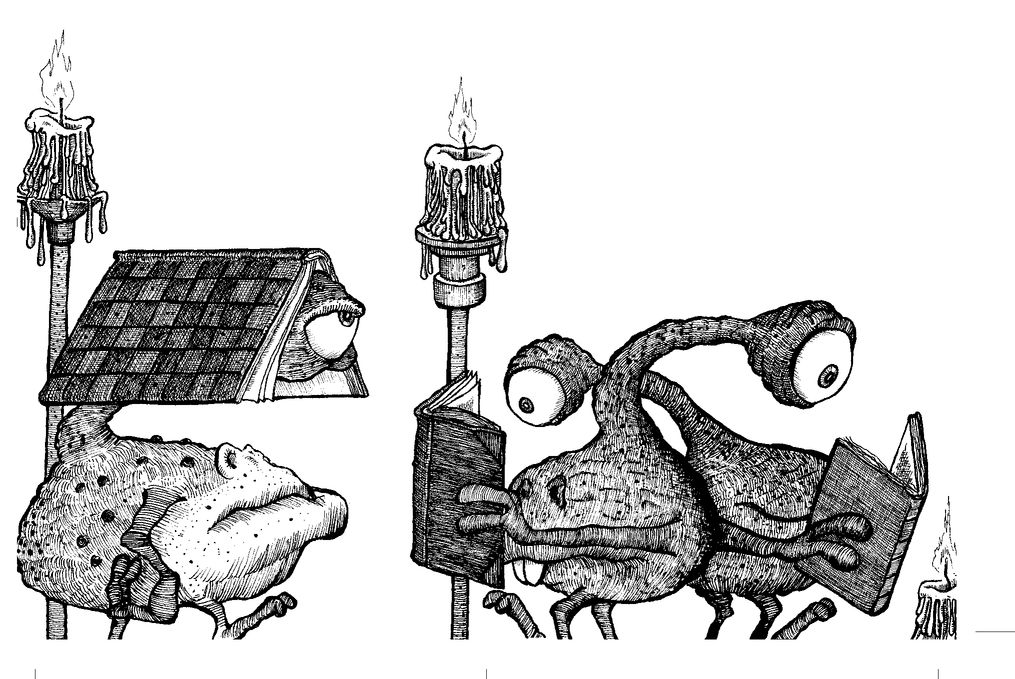

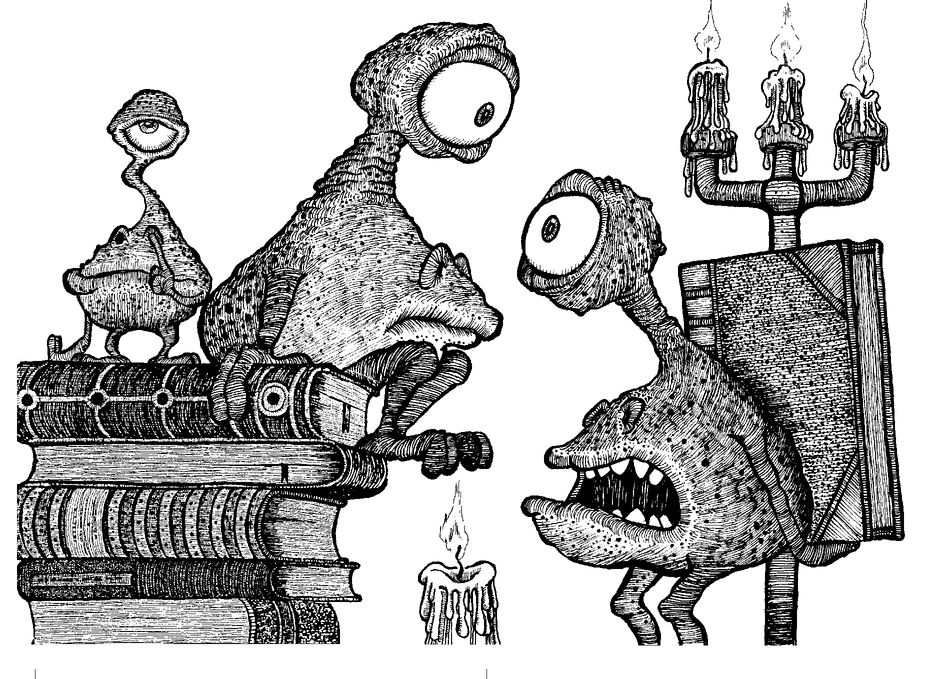

The rest of us paused too. The view was, to put it mildly, remarkable. But the most remarkable thing about it was not that the walls, roof, floor and even the stalactites were dappled with countless shades of brown and gleamed like polished leather. Nor was it the huge machine of weird design that stood in the middle. No, the most fascinating feature of the cave was its occupants: hundreds of little one-eyed creatures that all resembled Al, Wami and Dancelot but differed from them in certain details. Some were fat, others thin, some bigger, others smaller. Some had long, spindly limbs, others were short and sturdy, and each seemed to have a complexion all its own. The cave was teeming with them. They were reading at long tables, toting piles of books to and fro, pushing laden handcarts along or busying themselves with the gigantic machine.

‘That’s the Rusty Gnomes’ book machine,’ said Al, as if that explained everything.

The machine, which took the form of a cube some two hundred feet high, wide and deep, appeared to consist of rusty shelving. As far as I could tell at long range, the shelves were filled with books and in constant horizontal or vertical motion. Running round the machine on six levels and connected by numerous flights of steps were walkways on which more of Al’s fellow Booklings were bustling to and fro, removing or replacing books and operating various levers and handwheels. Not only the shelves but the whole huge contraption, including the catwalks and stairways, consisted of rusty iron. Its function remained a mystery to me.

At the foot of the machine were some long tables laden with large volumes, also handcarts, crates and more shelves filled with books. There were no phosphorescent jellyfish in the cave. The entire place was illuminated by candles, some in huge iron chandeliers suspended from the roof and others in ornate candelabra with numerous branches. Coal fires were burning in several big fireplaces let into the walls.

‘This is the Leather Grotto,’ said Wami. ‘Our library, academy and community centre. And these are our compatriots, the Fearsome Booklings.’

I was about to ask a question, but Dancelot got there first.

‘I’m sure you’re wondering about all this leather. It’s book covers - the whole cave is lined with them. We’d be happy to claim the credit for that achievement, but I’m afraid we weren’t responsible. It was the Rusty Gnomes, who also constructed the book machine. We polish the leather regularly to keep it looking nice and shiny in the candlelight. The atmosphere is ideal for reading. It smells good, too.’

That, at least, was true. The air smelt tolerable for the first time since I’d entered the catacombs. It was a trifle stuffy, perhaps because of the innumerable candles, but laden with pleasant aromas. The cave looked comfortable and elegant despite its size; in fact, it astonished me that a subterranean chamber could make such a cosy impression. I felt an urge to sit down and start reading right away.

‘Please note the skill with which the leather was hung,’ Al said proudly. ‘The most amazing thing is, not a single book cover was trimmed to make it fit. They went to an incredible amount of trouble to find the right cover to fill each space. It must have taken centuries to line the whole cave. The Rusty Gnomes were obviously very fond of books. They’re extinct, alas.’

‘Come on,’ said Wami, ‘we’ll show you round.’

We descended the broad staircase. I was still a bit dizzy from the effects of teleportation, but now my legs became really shaky. I don’t like walking down long staircases at the best of times, especially with people watching. I always have visions of making an utter fool of myself by tripping and tumbling down them. However, we reached the bottom without incident.

The other Booklings took no apparent notice of me while I was being shown round the cave.

The ones seated at the tables were muttering to themselves as they read. Others strode up and down, gesticulating and soliloquising, and many stood conversing in groups. The cave was filled with voices and their manifold echoes. The little creatures went on with what they were doing, but I could see out of the corner of my eye that they stared after me curiously as soon as I’d gone by. If I turned round, they quickly looked in another direction. Hundreds of them there might be, but I simply couldn’t feel scared of them.

‘Why do you call yourselves the Fearsome Booklings?’ I asked Al. ‘You certainly don’t strike me as very frightening. I pictured Cyclopses quite differently.’

‘It’s what the Bookhunters call us,’ the fat Bookling replied. ‘No idea why.’

‘No idea why, tee-hee!’ said Wami, smirking for some unknown reason.

‘But we don’t do anything to salvage our reputation,’ Al went on. ‘It’s wiser not to.’

‘Why?’

‘Listen, there are over three hundred kinds of Cyclopses in Zamonia. Some are peaceful and others warlike, some carnivorous and others vegetarian. The Demonocles feed exclusively on prey that is still alive and kicking. Other Cyclopses eat nothing but buttercups. There are Cyclopses with the intelligence of a house fly and others of above-average intellectual capacity - my innate modesty forbids me to tell you what

those

are called. The only thing the various Cyclopses have in common is their single eye, but in the public mind they’re doltish and dangerous creatures. We decided to take advantage of that prejudice.’

those

are called. The only thing the various Cyclopses have in common is their single eye, but in the public mind they’re doltish and dangerous creatures. We decided to take advantage of that prejudice.’

‘In what way?’

‘How many of us would have survived, do you imagine, if we were called the

Kindly Booklings

?’ Al retorted. ‘Or the

Nice Booklings

? This subterranean world is a brutal, merciless place. Down here the most highly respected creatures are the most ruthless and dangerous. In the catacombs a good reputation can be more lethal than a Toxicotome.’

Kindly Booklings

?’ Al retorted. ‘Or the

Nice Booklings

? This subterranean world is a brutal, merciless place. Down here the most highly respected creatures are the most ruthless and dangerous. In the catacombs a good reputation can be more lethal than a Toxicotome.’

Dancelot grinned. ‘Most Bookhunters are superstitious, fortunately,’ he said. ‘They’re shockingly uneducated individuals with a barbarous attitude to life. They believe in gods and devils. They love ghost stories and horror stories, and they like swapping Bookhunters’ yarns at their get-togethers. They all try to outdo each other with their tales of the Fearsome Booklings; in fact, many of them believe we practise witchcraft.’

‘Well,’ I said, ‘considering how you teleported me, they’re not so wide of the mark.’

The three of them nudged each other and giggled.

‘Teleportation, huh?’ Wami guffawed.

I had no idea why the silly little gnomes kept laughing. Perhaps it was just their own peculiar sense of humour.

‘Anyway,’ Dancelot resumed, ‘we encourage the Fearsome Booklings myth whenever we can. If we go our separate ways some time, it would be very nice of you to tell everyone you saw us devouring our own kind alive, or something of the sort. Or that we’re twenty feet tall with teeth as long as scythes.’

I remembered Regenschein’s stories about the Booklings. He had helped to spread the myth of their fearsomeness by including that kind of stuff in his book. I was just about to ask the gnomes if his name meant anything to them when we reached the huge machine.

‘When the first of us entered the Leather Grotto,’ said Wami, ‘this apparatus was too clogged with dust and dead insects to work. The Rusty Gnomes had probably become extinct many centuries before. But then we found the levers and handwheels. We tinkered with them and the machine suddenly started working again. Since then we’ve kept it in operation by oiling it regularly.’

‘But what does it

do

?’ I asked.

do

?’ I asked.

The three Booklings exchanged conspiratorial glances.

‘We’ll explain when the time comes,’ Al said mysteriously. ‘At present we use the machine as a library. It’s a bit tiring, the way the shelves never stop moving, but it keeps us in good shape.’

I saw the Booklings on the catwalks hurrying after the shelves as they removed books or replaced them. The rusty shelves kept superimposing themselves on each other or receding and disappearing into the interior of the machine. It made one dizzy to watch so many books on the move.

‘Shelves sometimes vanish for days on end, but they always reappear sooner or later,’ said Dancelot. ‘The machine never loses a single book we entrust it with. Come on, we’ll show you.’

We climbed a rusty staircase to the walkway on the lowest level.

Other books

The Lady of the Camellias by Alexandre Dumas fils

R. L. Stine_Mostly Ghostly 03 by One Night in Doom House

Todo por una chica by Nick Hornby

Taming Texanna by Alyssa Bailey

The Once and Future King by T. H. White

Shadows in Flight, enhanced edition by Card, Orson Scott

Manhattan Dreaming by Anita Heiss

Flossed (Alex Harris Mystery Series) by Elaine Macko

Seeing the Love by Sofia Grey