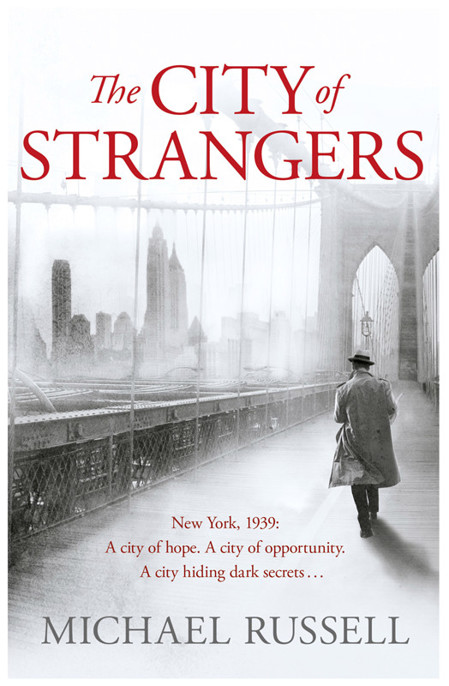

The City of Strangers

Read The City of Strangers Online

Authors: Michael Russell

The City of Strangers

For

Anya, Seren, Finn, Coinneach and Marta

And the Silver Meteor

To the Pennsylvania Station

Send but a song oversea for us,

Heart of their hearts who are free,

Heart of their singer to be for us

More than our singing can be.

‘To Walt Whitman in America’

Algernon Charles Swinburne

RPACN FEBSA HOGYH VTNOY IKSAO RYHOI VAUAR OAOIR OKWGQ MWAYA IERIL IETTM NNSTN ATAUA OIETH ARGTR YLHRA NASRI FOOAA AIALL TINYN LMENV NOOYG EEHOS OAOET GECTN: List of spies noted. Am forwarding it to Intelligence Director for his information. Are you able to carry out annihilation of all spies?

From

Decoding the IRA

Table of Contents

10. Pennsylvania Six-Five-Thousand

16. A Hundred and Twenty-Fifth Street

21. A Hundred and Sixteenth Street

Uptown

Mrs Leticia Harris, aged 53, who resided at 14 Herbert Place, Dublin, disappeared some time after 6 a.m. on Sunday, 8

th

March. The following morning her car was discovered at premises in Corbawn Lane, leading from Shankill to the sea. There were numerous bloodstains inside the car, and the police later in the day found a bloodstained hatchet in a shed adjoining her house, and also bloodstains on the flower borders in the garden. The police theory is that Mrs Harris was murdered in her own home and the body taken away in her car. Mrs Harris is the wife of Dr Cecil Wingfield Harris, 81 Pembroke Road, Dublin.

The Irish Times

West Cork, November 1922

The storm did not come suddenly. All day the wind from the Atlantic had blown hard and cold and fast against Pallas Strand. The grey sky sped past overhead, heavy, thick, turbulent. The noise was unceasing, humming and roaring, loud and soft, and loud and soft again, but always there, along with the beat of the sea crashing endlessly against the white curve of sand. The farm lay back from the strand, behind a scattering of tufted dunes and a row of wasted trees, bent and twisted from long years of bowing and creaking before the wind, yet somehow always strong enough to stand. Indoors and out the blast of the wind battering the farmyard and the buildings had been constant, but still the rain hadn’t come.

The boy was in the yard, leaning into the wind to stand, scattering leftovers from a bucket to the ruffled and bad-tempered hens. He was seven; it had been his birthday only a week ago. He shouted and laughed as the puppy that had been his birthday present danced around him, darting and leaping, behind, in front, through his legs, trying to snatch the bacon rinds before the hens could get them. His father was in the barn, milking the three black cows. His mother was in the kitchen, peeling potatoes. He didn’t hear the two vehicles driving along the track from the main road. The wind was blowing the sound away from him. It was only as the dog turned sharply from the scraps and started to bark that he saw them.

He knew them well enough. The long, sleek Crossley Tourer came first, with its top open even in the wind, and its battered leather seats. He loved the Tourer and its white-walled tyres, despite the men inside it. The other one was different; a Rolls Royce armoured car with its squat turret on the back and its .303 Vickers machine gun sticking out through the letter-box sights. As the dog zigzagged angrily round the wheels of the Crossley, snapping and snarling, it stopped; three uniformed men got out. The boy knew them too. It wasn’t the first time they had driven into the farmyard at Pallas Strand.

There was a young lieutenant and two great-coated Free State soldiers. The lieutenant smiled; the boy didn’t smile back. No one got out of the armoured car; its turret moved in a slow, grating arc as the machine gun scanned the yard. The puppy kept up a furious yapping, now round the feet of the intruders, but a kick sent him flying across the muddy yard. The boy turned to find his father standing behind him. There was another man too, his uncle. Where his father was calm and steady, he could see the fear in the other man’s eyes. And his mother was there now, in the doorway of the house, wiping her hands dry with her apron. The lieutenant stepped towards the boy’s father.

‘You’ve heard what happened on the Kenmare road?’

‘I heard something.’

‘So where were you yesterday?’

‘I was here. Where else would I be?’

‘You were seen in Kenmare the day before, with Ted Sullivan.’

‘Who says?’

‘I do.’

The boy’s father shrugged.

‘There’s a Garda sergeant dead at Derrylough. A mine,’ said the officer.

The boy’s father shrugged again.

‘Someone said something about it.’

‘There was no mine on Tuesday. The road was clear.’

‘I wouldn’t know, Lieutenant. That’ll be your business.’

‘But Ted Sullivan would know, I’d say.’

‘That’ll be his business then. You’d need to ask him so.’

‘Maybe you’d know where he is then?’

‘Well, he wouldn’t always be easy to find.’

‘Unless you were an IRA man.’

‘There’d be a lot of IRA men in West Cork. You’d know yourself. And it’s not so long ago you fellers would have called yourselves IRA men.’

The boy’s father smiled. It was a mixture of amusement and contempt. It was a familiar conversation, empty, circular, quietly insolent; all the lieutenant’s questions would go unanswered. But he knew that. He turned to one of the soldiers and nodded. The man walked forward and slammed the butt of his rifle into the farmer’s stomach. As he collapsed to the ground the boy stepped between his father and the soldier, saying nothing, but glaring hatred and defiance. The soldier laughed. The boy’s mother ran forward across the yard, but her husband was already struggling to his feet. He looked at her sharply and shook his head. She stopped immediately. The boy turned to his father. The noise of the wind rose and blasted. The man smiled, despite his pain, and put his hand on his son’s head, ruffling his hair. The lieutenant put a cigarette in his mouth. He hunched over his hands for several seconds, trying to get his lighter to catch it. After a moment he straightened up, drawing on the smoke.

‘Let’s see what you’ve got to say at the barracks.’

The soldier who had knocked the boy’s father down took his arm and dragged him towards the Crossley Tourer. The other soldier covered him with his rifle. The turret of the armoured car creaked slowly as the machine gun swept round the farmyard once more. The boy watched as his father was pushed into the back seat of the car. Neither his mother nor his uncle moved. They had seen it before; it was always the same; the same questions and no answers. He would come back, beaten and bruised, but he would come back. The soldiers got into the car. Then the Crossley Tourer and the armoured car swept round in a circle in the farmyard, through the mud and the dung, and drove up the track towards the road to Castleberehaven, the dog chasing behind, still barking and snapping.

The woman walked forward. She took her son’s hand and smiled reassuringly. It would be all right. These were the things they lived with, that they had always lived with. Even at seven years old he was meant to understand that. The soldiers who had taken his father away were traitors; men who had sold the fight for Irish freedom for a half-arsed treaty with England that was barely freedom at all. Traitors were to be treated with contempt, not fear. Then his mother turned to his uncle, his face white, his fists clenched tight at his side. The fear was gone; now his face was full of anger.

The boy had once asked his mother why his father seemed to have no fear and his uncle, sometimes, had to hide his shaking hands. ‘A man can only give what he has,’ she told him. ‘If he gives it all, no one can ask more than that.’ She was very calm now. None of it was new to them. Three years ago it had been the English Black and Tans; now the men in uniform were Irish, but the same sort of shite. Rage was to be nurtured, as it had been for centuries. There would always be a time to use it.

‘You take the bike and go up to Horan’s. They’ll get a message to Brigadier Sullivan. He’d better know. And we’ll finish milking the cows.’

The boy’s uncle nodded and walked quickly away. The woman and the boy went into the barn. For a moment, as his mother put her arm round him and squeezed, the boy smiled again. He did know it would be all right.

They waited all that evening, wife and brother and son. The rain had finally come just before dark, beating in from the sea, and the wind began to drop. As night fell a more welcome car pulled into the farmyard. The IRA brigadier said the man was where they expected him to be, in the police barracks in Castleberehaven, on the other side of the peninsula. The Crossley Tourer had been seen driving in through the gates around four o’clock. The IRA had someone inside the barracks; when the man was released they’d have the information immediately. He would be collected and brought home. The Free Staters had pulled in a number of volunteers that afternoon; it was the usual game; most of the men were already home. They only had to wait.

When the boy went up to bed there was no sense of anxiety in the house. The rain was falling outside, but the storm was quiet. Lying in his bedroom under the eaves, listening to the rain rattling comfortably on the roof, he drifted off to sleep thinking of the days when he would hold a rifle in his hand and fight the fight his family fought now. But when he woke abruptly in the early hours of the morning, he knew something was wrong. The rain still fell, but the house wasn’t at its ease any more. He could hear voices downstairs; his mother’s, his uncle’s, and others, a woman, several men. He could make out no words, but the voices no longer echoed the assured tones of the brigadier. There was anxiety; he knew what that was. The voices grew louder and then someone said something to quieten them; but the quiet wasn’t really quiet; it was a series of harsh, adult whispers that only intensified the anxiety.

He got out of bed and crept across the room. He knew where each floorboard creaked; he stepped slowly and carefully. At the door he turned the knob and opened it just a crack. The lamps were still burning downstairs. He didn’t know the time, but he knew these were the early hours of the morning. The voices were still unclear. The broken words and overlapping phrases that came up the stairs wouldn’t fit together. ‘Five fucking hours ago – they drove him out, he was in the car – it was ten o’clock – no, the ones at Ardgroom were from Kenmare – Gerry Curran didn’t even pick up a gun – they pulled him out of bed – they already knew where the explosives was buried – so where is he?’

The voices stopped. People were moving downstairs. The door into the farmyard opened. The boy tiptoed to the window. He pulled back the curtain and looked down. Two men were walking across the farmyard. They carried rifles. His uncle followed, a few steps behind; he stopped and turned back to the house. His mother was there now, standing in the rain. His uncle stepped back. He put his arm round her and pulled her to him. It was the same gesture of reassurance the boy had received from his mother as they walked to the barn to milk the cows, but everything about the way his mother stood now, unmoving, unaware of the rain falling on her, said that she wasn’t reassured.

His uncle picked up the bicycle that lay on the ground by the door. He got on it and rode away. Ahead of him the two other men were on bicycles too, their rifles slung over their backs, their hats pulled down on their heads. The three of them rode out of the farmyard and within seconds the rain and the darkness had swallowed them. The light from the open door shone on his mother as she watched them go. The boy looked down from the bedroom window. It seemed a long time before she turned away from the darkness, back into the house. The door shut. She did not come upstairs.