The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (33 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The monk horseman who had come to see me in my mountain retreat was now returning to Drölma Lhakhang. I gave him a letter to Akong Tulku telling him that I had decided to leave on the twenty-third and that, if he wanted to come with me, he must discuss the matter with his monks and come to an early and firm decision. I thought it unlikely that Drölma Lhakhang would be left in peace after what had happened in other parts of Tibet and particularly at Surmang. Should he come with me, I promised his monastery that I would do my best to look after him, but I realized that such a journey might be dangerous for both of us. My own date for departure was fixed and I had every intention of sticking to it. Yak Tulku might be coming with us and, if he decided to do so, I had told him that his baggage must be severely cut down. We should have to keep a small party; with every additional person the danger would become greater and my own responsibility would also be increased; moreover, there was always the possibility that others might wish to join us on the way; this was how I wrote to my friend Akong.

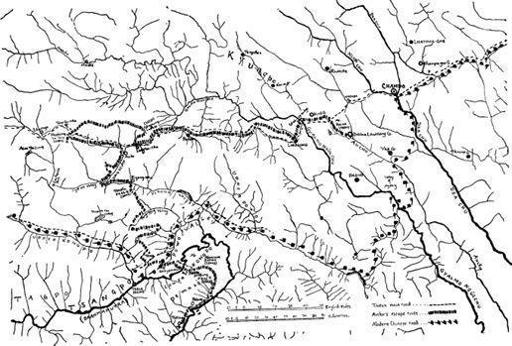

Until the 22nd I remained in the village and then set off at night for Drölma Lhakhang which I reached at six o’clock the next morning after a roundabout journey avoiding villages, while a tremendous snowstorm was raging. Both Akong Tulku and my bursar had tried to keep our plans secret, but the news of my intended departure had leaked out and on my arrival at the monastery I found a number of monks and villagers assembled who wanted to receive my blessing and to consult me about what they themselves should do. Some of them suggested organizing local resistance. I had very little time to talk to them and none to give any individual advice, so I spoke to the crowd in the assembly hall. I told them it would be useless to fight and, since I did not even know myself where I was going, I could offer them no concrete suggestions. At the moment I was thinking of Central Tibet; however, they must realize that there was danger everywhere. I told them to remember the teaching we had shared during the wangkur. Before I said goodbye they all filed past me to receive a blessing, after which I left hastily for fear of further delays as more and more people were arriving.

Akong Rinpoche had decided to come with me with the approval of his monks, but my bursar had changed his mind; he could not bear to leave so many treasures behind while I, for my part, kept firmly to the decision to travel on horseback with a few mules to carry the basic necessities for the journey. It was arranged for a Lhathok woman to inform my monks at Kyere about my departure. After all this delay, our party could not even wait to have a meal, though my attendant and I had not eaten since the night before, so we set out on empty stomachs. Yönten came with us as acting bursar and the two attendants who had been with me in the Valley of Mystery were also of the party. Akong Rinpoche brought his two brothers and we were also joined by Lama Gelek, the monk who had taken the kalung when I gave the wangkur at Yak. A young novice from Drölma Lhakhang and an older monk from the retreat center also came with us. The older monk was a very spiritual man, prepared to face any difficulties and dangers.

We started with a tearful send-off from all the monks of the monastery. It was a desolate moment for Akong Tulku who was leaving his own monks, especially the senior ones, who had brought him up with such loving care. My bursar accompanied us as far as the nunnery which was to be our first stopping place. We had some thirty horses and fifty mules with us. The neighboring villages had been asked to watch out and report if any Communists were in the district.

On our arrival at the north nunnery I found the nuns very calm and thoughtful over the turn in affairs. They asked me to advise them what to do, saying they understood that they must accept whatever fate might bring. Some of the nearby villagers came to see me and we all talked for about an hour. As soon as there was a pause, the nuns offered us a meal which was very welcome. After we had eaten I went up to the hermitage and found the nun who was in retreat there. She was more concerned with my well-being than with her own personal danger. We had a spiritual talk and I encouraged her to consider the disturbances of this life as an element in her meditation.

Our party spent the night in the shelter of the nunnery and we talked until late in the evening. During the day all the baggage had had to be sorted and properly packed. No one except the nuns knew that we were on our way to escape or for how long we would be staying at the nunnery; in fact, we disappeared after an early breakfast.

Not long after, we met a man who had just crossed the river by the bridge without meeting any Chinese; this was cheering news. The next night we stayed in an isolated house belonging to a celebrated doctor, who welcomed us warmly. He specialized in the use of herbal remedies and had several sheds where he kept a stock of local herbs together with other medicines imported from India. A wonderful meal was put before us, in which special spices were used to flavor dishes our host himself had invented. He was convinced that at the moment we had nothing to fear from the Communists. Next day he gave us detailed instructions about what food to eat or avoid on our journey, also telling us where the water was good, bad, or medicinal.

We set out very early in the morning; some of the neighboring villagers, however, had somehow got to know that we were in the district and came to ask for my blessing and also for advice and this delayed us somewhat. Our next stop was by a lake surrounded by five mountains, known as the Five Mothers; these had been held to be sacred by the followers of the old Bön religion. Here we had tea and then changed into ordinary Tibetan civilian clothes with European felt hats such as many people wear in Tibet. As I have mentioned before, such a change of clothes has a bad psychological effect on a monk, it gave one a sense of desolation.

Our track now led us over heights, with the land sloping down to a distant river. A message had been sent to Kino Monastery which lay some miles from the bridge, announcing our coming. On the way down we were overtaken by Akong’s tutor from Drölma Lhakhang who had followed us to see that all was well with our party. A little farther on we met a traveler coming from the direction of the bridge; he too reassured us saying that there were no Chinese in the vicinity. Since the monks at Kino had been forewarned, they had prepared a small procession to welcome us at the entrance to the monastery. Its abbot was a married lama who lived outside the precincts but was still in charge of the community, while the khenpo (master of studies) lived within the monastery and acted as deputy abbot. Being received with all the traditional monastic ceremonial, I felt a sense of personal shame at appearing in lay dress. During our three days’ stay there many people from surrounding villages came to ask for a blessing and to put their personal troubles before me. We had to be particularly careful in this place since it lay near the bridge, so that there was always the possibility of the Communists coming this way, since Pashö lay only a few miles upstream, on the river Pashu which joined the Gyelmo Ngül-chu just above the bridge; this gave the place a certain strategic importance.

Kino Tulku and his wife now wanted to join our party. Unlike Yak Tulku, he was quite prepared to leave all his possessions behind. His wife came from near Drölma Lhakhang and they were both great friends of Akong Tulku. He said that since his friend was leaving and the situation with the Communists was becoming ever more menacing, he thought they should escape with us. He and his wife made immediate preparations for the journey and decided to bring with them two monk attendants, five horses, and eleven mules. A man with his wife and little daughter also asked if they could join us. They had sold up their home and bought three horses in addition to the two they already possessed.

According to information received locally, if we could cross the bridge the country on the farther side would be safe as it was under the administration of the Resistance. We made ready to go on and Akong’s tutor returned to Drölma Lhakhang; he was in great distress over having to leave us for he realized that this was a complete separation from his beloved abbot.

We soon reached the Shabye Bridge which we crossed without difficulty; on the farther side we met a guard of the Resistance army who checked our party to ascertain that we were not carrying arms. One of my attendants was carrying a rolled-up pictorial scroll over his shoulder and the guard thought it looked suspiciously like a gun! When we had been cleared we were given passports. We enquired what steps were being taken to protect the area and were told that the whole district was being guarded and they thought that the Communists would not be able to break into it. He was very optimistic and said that the Resistance was even preparing to attack. We told him that the Communists had spread a report that the guerillas forced His Holiness the Dalai Lama to leave Lhasa early in March and that he had escaped and was now in India; also that Lhasa was now entirely under Communist control, though we ourselves did not believe this to be true. The guard likewise thought that this report was merely Chinese propaganda. Most of our companions were greatly cheered and muttered among themselves that such tales as these were not to be taken too seriously.

All the party felt relief at not being in immediate danger. We stayed the night in a house in the village and Kino Tulku’s monks returned to their monastery. The next day, getting up very early before sunrise, we started off to cross a high mountain range by a very steep zigzag track; our animals had to stop frequently to regain their breath; we met some of the Resistance soldiers coming down it. At the top we saw stone defense works which had been built on both sides of the road. Some of the soldiers came from the Lhathok district and among them was a doctor who knew me. He told me that he had left his home as a pilgrim and had joined the Resistance army in Lhasa before the crisis. All the soldiers were tall, well–set-up men and looked very warlike; most of them carried rifles but a few only possessed old-fashioned muskets. The young soldiers seemed enthusiastic and proud to wear their military medals hung on yellow ribbons, inscribed with the words

National Resistance Volunteers;

they were all singing songs and looked very cheerful. My personal attendant Karma Ngödrup, who had a simple optimistic nature, was much impressed with them; he said he felt sure that the Tibetans would get the better of the Chinese for, according to the law of karma, we who had never molested other countries must now surely deserve the victory.

On the farther side of the mountain we stopped and spent the night in tents, and the following day we reached Lhodzong, where we met a man from Kino who was partly in charge of the Resistance troops. He told me his story, how he had met the commander Andrup Gönpo Tashi, who had impressed him as being a man of outstanding character; he thought that with such a leader directing their forces, the Resistance must be successful. My informant had been a senior official with the Riwoche administration and had been held in the greatest respect by everyone in the area. Kino Tulku wished us to consult him about our escape plans but, when we did so, he was unable to give us any useful advice; and in fact, he only expressed the opinion that it was unnecessary for us to leave the country.

Reaching Shi-tram Monastery, we found the monks there quite calm and engaged on their ordinary routine, but beyond that point we began to meet with difficulties. On the main road to Lhasa there were so many Resistance soldiers going in both directions, that very little grazing was available, added to which we found all provisions very expensive. We decided therefore to bypass the main road and follow a more roundabout track which brought us near the home of some of Kino Tulku’s friends with whom we stayed for several days. The young abbot of Sephu, who had been one of my pupils at the wangkur, came to see us while we were there. He wanted to join our party with his mother, his tutor, and several monks. I explained to the tutor that this escape was likely to be a difficult business; we did not yet know where to go, there was so much uncertainty about what had happened at Lhasa itself; therefore I advised him to think things over carefully before deciding whether to join us or not. Supposing that the monks of his monastery wished to come with him, this would make further difficulties and would endanger the whole party. When ten of us left Drölma Lhakhang it had been unanimously agreed that the party should be kept small; but already we had been joined by other people together with their baggage. The next morning the tutor came back to tell us that his abbot, who was in a great state of excitement, was determined to come with us. He had sent a message to his monks telling them that he had decided to escape but that, since I had insisted that it would be impossible to travel in a large group, they must understand that they could not come with him. When the young abbot joined us he brought about twenty more mules to add to our transport. After several more days on the road we came across Ugyen Tendzin, a young monk going on pilgrimage to Lhasa. He also asked to join us, and Kino Tulku told him that he could put his baggage on one of his own mules. We found him most helpful with loading and unloading the animals, and afterward, at critical moments of the journey, he proved an invaluable member of our party, full of resource and courage.