The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (35 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

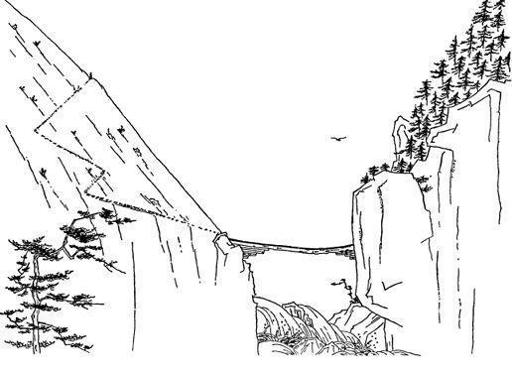

When Yak Tulku’s mules arrived we decided to stay where we were for another day or two to concert our plans. Looking at the camp, it appeared enormous and I wondered how we would ever manage to escape with so many men and animals. We had to push on, and on our way down all we could see were endless ranges of mountains stretching out before us. After a couple of days we came to a place called Langtso Kha where we camped by a small lake surrounded by rocky hills. We were told that Resistance troops from Central Tibet had already arrived at a nearby village, which meant additional complications for us, for at this point the valley entered a steep gorge where perpendicular rocks in places went right down to the river, so that the track could not be carried further on the same side of the water and travelers had to get across to the opposite side. For this primitive bridges had been built. Even then, there were parts of the gorge which were so steep that no path could run alongside the river; in these places the pathway had been taken over the rocks and, wherever it was blocked by impassable rock faces, platforms made of planks had been built around the obstacle, these being supported on posts fixed into the cliff below. We were not sure if these would be strong enough for heavy loads such as ours and the road all along was so narrow that it was evident that, if we happened to meet Resistance troops coming from the opposite direction, neither party would be able to pass. However, we could not stay by the lake because of the difficulty of finding grazing for our many animals, for what little there was was needed for the Resistance army.

We sent some messengers ahead to enquire if further troops were to be expected; they were told that at the moment there was a lull, but more men were expected shortly, and some important leaders had already arrived. Yönten and Dorje Tsering went down to the village to buy supplies and to see the officer in command. He told them that fighting was going on in several places, but did not mention Lhasa. He also said that he was expecting more troops at any moment. He had found the bridges across the river and the platforms on the road were in very bad condition and was arranging for their repair. There was nothing for us to do except to wait where we were. Meanwhile the weather had improved; I had my books with me so I started a study group. Having finished the book on meditation, I began to work on an allegory about the kingdom of Shambhala and its ruler who will liberate mankind at the end of the dark age.

Bridge over the Alado Gorge

.

Akong Tulku with his young brother and myself used to go for delightful climbs on the surrounding mountains which were covered with flowers. The local landowner proved very friendly; he frequently invited the senior members of our party to meals and allowed us to graze our animals on his land; also peasants came to see us and sold us some food. One day Karma Tendzin came through with his detachment; they were returning from Lhasa after its fall to the Chinese. We had known for a long time that he had left his home to join the Resistance. Numbers of refugees were coming back along the road together with the soldiers, and we realized that it would be impossible for us to travel against the traffic. Some of the refugees came and camped near us by the lake. They told us all sorts of rumors; some said that the Dalai Lama had come back, others, that the Chinese troops were advancing toward our area. With such crowds of people escaping, there was a growing shortage of food and grazing, and our friend the landowner and the neighboring villagers were getting very anxious about it. In comparison with these hordes our party seemed quite small. We knew, however, that we must make plans to move elsewhere, and learned that if we retraced our steps we could follow another valley going northwestward. So we thanked the landowner for all his kindness and broke camp.

It was now early June. We traveled for about a week; each day we had to cross a high pass. One day, we passed a man who came from Lhathok, he told us that he had escaped with some nine families, with one Repön as leader. They had brought all their possessions and animals with them and had established themselves in a small valley nearby, where the country was very open with good grazing. The following day they all came to see us bringing barrels of curd, cheeses, and fresh milk which we much appreciated, for on our travels we had had all too few milk products. They suggested that they might follow us, but when they realized that we ourselves did not know where we were going, they thought that they also should make no plans for the time being. I gave them my blessing and we moved on. The next day we came to Khamdo Kartop’s camp; he had been one of the king of Derge’s ministers, and was a follower of Jamgön Kongtrül of Sechen; he had some forty families with him. He told us how his party had fought their way westward in spite of having women and children with them. Their young men were strong and experienced; they had been successful at Kongpo and had captured some of the Communists’ ammunition. Now they were in the same position as ourselves, not knowing where to make for. Khamdo Kartop had the same views as myself, he did not want to be responsible for looking after other refugee parties. He knew that there was no chance of going toward Lhasa since the main road was strictly guarded and said he thought that the Resistance army still had their headquarters at Lho Kha; they had fought with great bravery in Central Tibet, but had too few men and very little ammunition. He had heard that Andrup Gönpo Tashi had gone to India and, like myself, he was sure that we must all try to get there. In any case we could not stay where we were, on the border of the territory controlled by the Resistance.

I returned to our camp to hear the news that Lama Ugyen Rinpoche was leading a party of refugees from the east in the hopes of reaching India. He was going south by a holy mountain which was a place of pilgrimage. Kino Tulku knew all about the country there and thought that it might be a good plan to go toward India by the Powo Valley. We held a meeting in the camp to discuss the situation. Some thought that we should join up with Khando Kartop’s party, but none of us were in favor of fighting, so this did not seem to be a very sensible move. Others suggested that we should follow Lama Ugyen. However, our party for the most part wanted to keep separate, for if we joined with other groups our numbers would become dangerously large. Since we knew that we could not stay where we were, I decided that we must continue southward at least for a few months, and by that time we would know more about the state of affairs in Tibet; refugees were coming in from all directions and we would soon learn what was happening everywhere. I sent Dorje Tsering to inform Khando Kartop of our plans. I said that in the future we might wish to cooperate, but for the present I had decided to act on my own.

A further three monks had joined our party; they had no transport and Yak Tulku took them on to help him. Before we left, Repön, who was directing the refugee encampment, sent his son to have a further talk with me. His group thought that they should sell some of their things to buy horses and then join my party. He wanted to know what we had decided to do and if I would allow them to come with us. I told him that we were still uncertain about everything and that each day things were becoming more complicated. He replied that even so they all intended to follow us. I advised him not to part with his animals, or to follow us too soon, because all the routes were overcrowded with refugees and we might not be able to get through. However, they went on getting rid of their possessions.

Some soldiers came along who had escaped from Norbu Lingka, the Dalai Lama’s summer residence outside Lhasa; they gave us a graphic account of what had happened there. They had witnessed the Chinese shelling the building and seen some of their fellow soldiers killed. No one knew whether the Dalai Lama was still within the walls; there was, however, a suspicion that he had escaped. They had also seen the Potala being shelled; the bombardment had begun at a signal from a Communist gun. After the attacks on the Norbu Lingka and the Potala there was no possibility of further fighting, for the Chinese had taken up positions in big houses in the town and were firing from them. It was obvious that all this had been prepared for some months previously. These men had escaped, but a number of Resistance soldiers would not leave the place and they had all been massacred.

Another man told me how he had left Jyekundo with a large group of refugees. They had reached a place halfway to Lhasa in the flat country round Changthang when they were sighted by Chinese airplanes and Communist patrols attacked them from all directions. The fighting was severe; among others the abbot of Jyekundo Monastery was shot and all the wounded were left to die, while the survivors from the battle starved to death as the Communists had taken all their food and possessions. The refugees had, however, actually succeeded in shooting down one of the enemy planes. There were many different groups of refugees all around that area, and the Chinese were everywhere. My informant’s particular camp had been attacked seventeen times. On one occasion, when the group was trying to go forward and most of the men had gone ahead to secure a passage through the surrounding Communist troops leaving the women and children in the camp to follow after them, a husband and his wife had put their three young sons, aged between eleven and eight, on their horses, and while they themselves were saddling their own animals the boys’ horses took fright and bolted. The parents took it for granted that the horses were following others leaving the camp, so went on themselves to the agreed camping ground; however, on reaching it there was no sign of the children and the mother in despair jumped into the river.

The man who spoke to me had witnessed the whole tragedy and went on to tell me how several days later when he was scouting round he had discovered the three boys sheltering from the rain, under a rock; two of their horses were nearby, the third was dead and the children were starving. The eldest boy had tried to cut out some of the dead horse’s flesh, but his small knife had been useless for the task. The children asked him where their mother was. Since another attack from the enemy was expected at any moment, the man could not take the children with him; however, he managed to arrange with some nearby herdsmen to look after them. He had later met their father in Lhasa and told him how he had found the boys.

One important piece of news reached us about that time: We were told that Gyalwa Karmapa had left his monastery some weeks before the fall of Lhasa, with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche and his brother and the newly found incarnation of Jamgön Kongtrül of Palpung, who was still an infant, also the young Tai Situ abbot of Palpung; many abbots and lamas had traveled with them. They had gone through Bhutan to India and had been able to take some of their possessions with them. This news left my monks in no further doubt that we too must face the hardships of escape. They could not, however, understand why, if Gyalwa Karmapa had arranged to escape himself, he had given no indication of his plans when I wrote to him from Drölma Lhakhang. I explained to them that none of us could advise others in such a situation; I was in the same difficulty myself when asked for my advice, since I did not even know where our own party could find refuge.

Some of the troops who were passing through told us enthralling stories; the Resistance soldiers who had fought at Kongpo had been very brave, but they had been forced to retreat, for they could do nothing against the superior arms of the Chinese; their spirit was still unbroken and they were ready to carry on the fight at any time.

We now made our way across a range of mountains in a southwesterly direction and after negotiating the high pass of Nupkong La we reached the China-to-Lhasa main road in front of the bridge at the western end of the dangerous passage through the gorge which we had not dared to attempt before. There were many refugees going the same way. We camped in a small field from where we could see the road. I was apprehensive and scanned it carefully through field glasses: It certainly looked impossible; however, when I saw a man with some baggage mules going across it, I thought it might be feasible. We asked some villagers for their help with our animals and started off at daybreak the following morning. Fortunately no one was coming from the opposite direction. We found that as long as the animals were left to themselves they were all right; we were able to reach the last bridge safely about noon and stopped at the first small camping ground beyond it, for with so many refugees on the way, we thought we might have difficulty in finding another suitable place.

Nearby, we met a number of monks from Kamtrül Rinpoche’s monastery of Khampa Gar, among them the same Genchung Lama who had served as chöpön (director of rites) for the wangkur at Yak; with him he had his sister who was a nun, and there were also a number of villagers in his party. The monks gave me a distressing account of how their monastery had been invaded by the Communists. They had all been imprisoned and the senior lamas shot one after another. Only a very few monks had escaped from the monastery itself, the party on the road having mostly come from the retreat center; it was sad to see how, after so many peaceful years of monastic life, they now found themselves in this tragic position. They were, however, enormously thankful that their abbot had been able to escape to India. I was a little afraid that they would want to join us, for our party was already far too numerous; before they could suggest anything, I hinted that we had no set plans ourselves; I said we had already been forced to change plans suddenly several times. However, they decided to try to get to India from the west side of the gorge. Only the chöpön and his sister asked to come with us; they each had a horse and some mules for their baggage.