The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One (38 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume One Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

The knot of eternity.

Traveling the Hard Way

W

E WERE NOW LEFT

with only our own party, and there were three alternative ways for us to follow. The first was for us to try to cross the turbulent Nyewo River in spite of the fact that we had very little information about the route and did not know whether any Chinese were in these parts. Moreover, should we attempt to go this way, we would have to leave our animals behind and go on foot. Another way would be to go on horseback through Kongpo keeping to our side of the Nyewo River; this might be very dangerous, for it was more than probable that Chinese troops would be in occupation of much of that area; besides, there would be an added difficulty in our having to cross the very high Lochen Pass. Thirdly we might join forces with Kartop and perhaps also with the queen of Nangchen in order to break through to the southwest by fighting our way. Since a move was necessary, I decided to go first to a small valley I knew of, near the point where we would attempt to cross the torrent if we decided to do so. It had a very narrow entrance which opened onto broader land suitable for camping; the grazing was good and there were no villages in the valley, nor had any other refugees discovered it. We traveled by night, keeping on the alert all the time in case we should hear the sound of guns. A man was left in the Nyewo Valley to report any further news of the Communists’ approach. The following day he came to tell us that nothing had happened and that the valley was deserted. Headquarters sent me a message to say that the Chinese had come from Kongpo through Lochen Pass on their way to Nyewo, but the Resistance troops had attacked them and captured one of the Chinese guns, also rifles and much ammunition. The local people who had rushed off with the refugees were now returning to their homes. They wanted our party to come back and begged that I should stay with them to perform various rites. However, I decided to leave the camp where it was and went backward and forward myself to perform whatever rites were needed.

The suddenness of the Communist scare seemed to me to have come as a warning that we might expect them in our area at any moment. They were definitely intent upon occupying this small pocket of country. We heard airplanes at night. I consulted all the senior members of our party and it was decided that we must move and that the only possible route was the one across the difficult river, which definitely meant traveling on foot down the gorge. Ugyen Tendzin said that, if I was determined to go that way, he would do his best to help in the crossing. He had previously suggested that we should procure some leather suitable for building coracles; now he immediately set to work on having one made. When it was ready we took it down to the river to make the experiment. He attached the coracle to the shore with a long rope; then got into it himself and paddled across; he found it quite easy to reach the farther bank. A second coracle was put in hand. I sent some of our horses and baggage mules back to Tsethar with a message to tell Akong Tulku about our plan, suggesting that his party should follow. The rest of the animals and baggage I sent to Lama Ugyen, with a letter saying, “The wind of karma is blowing in this direction; there is no indication that we should do otherwise than attempt this way of escape. Events are changing so suddenly, one cannot afford to ignore the dangers. I hope you will make up your mind to carry out your plans without delay and that they will work out well with the blessing of Buddha.”

With all this public activity of building coracles and sending the animals away our plans leaked out. Rep̈on’s group and the refugees under Lama Riwa together with various other small parties returned to join us; they camped all around our valley which was really too small for them to share. All of them were determined to come with us and they expected me to assume the leadership of the whole party which now amounted to 170 people. We still did not know whether the Communists were on the other side of the river or not. I resorted to takpa (divination); it indicated that no Chinese were there. We organized some porters among the local people, so were still able to take a part of our possessions to be bartered later for necessities. I had about thirty porters to carry my own things and altogether one hundred were needed for the whole party.

We started our expedition with two coracles each holding eight people; Ugyen Tendzin had taught a second man to paddle, though he did most of the work himself. I had a great feeling of happiness that we were starting at last. We had just got under way when a messenger arrived from Karma Tendzin asking me to join forces with his group, but I replied that his offer had come too late, we had already made our plans and could not go back on them. The soldier who brought me Karma Tendzin’s message had been in the fight at Lochen Pass; he gave me a vivid description of it all. He was a member of some patrols on the mountainside who were hiding behind bushes overlooking the pass. They watched the Communists creep forward and place their guns in position to attack the front line of the Resistance troops, who were still behind their entrenchments. The patrols waited until the attack began and then closed on the enemy from all sides. The soldier himself had jumped on a Chinese soldier just as he was about to fire a gun which the Resistance troops succeeded in capturing.

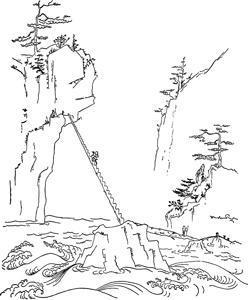

Many of the lamas and refugees in Nyewo sent kind messages when they heard that we were leaving. A man had gone ahead of us to the next village to warn the inhabitants of our approach, for visitors seldom came to this remote part of the country and we thought our large numbers might cause alarm. Everyone had to carry some of the baggage; my attendant disapproved of my doing this and wanted to add my load to his; I had to make it clear to him that each of us must do his share; Kino Tulku carried the heaviest load. We felt that we must acclimatize ourselves to this difficult way of traveling, so we made our first day a short one. The rough track ran beside the river which now plunged through a rocky gorge. It was obvious that no animal could be brought this way, for there were a lot of huge rocks on the track with deep crevices between them, spanned by fallen pine trees; men could only move in single file. At night it was difficult to find enough space to lie down and our bedding was of the simplest. The country here was much warmer and damper than the parts we had come from, with more luxuriant vegetation. The nearer we got to the village of Rigong Kha the worse the track became, till we were faced with a very high cliff coming right down to the river. I was horrified when I looked at a very sketchy zigzag path going up this cliff. I had expected a track, but there appeared to be nothing more than a broken chain dangling at intervals, beside what appeared to be little cracks in the rock. One of the porters told me to watch the first of their men going up; he had a load on his back and never seemed to hold on to anything, but just jumped to the footholds cut in the rock; I thought I could never do it. Some of the younger men failed to get through unaided and had to hand the baggage they were carrying to one of the porters. The latter offered to carry some of the older men on their backs, but this kind offer was not accepted, it seemed too dangerous; instead they went up very slowly roped to porters in front and behind. When they got halfway some were so frightened that they refused to move and the younger people had to be firm with them saying that the porters were not going to hold on to a stationary person; they must pull themselves together and carry on. All this took a very long time. I was one of the last to attempt the passage and, while waiting, I had time to study everyone’s methods of tackling the awkward passage. The porters, by agreement among themselves, had selected the best men to carry me up, but I said I would prefer to walk. What rather disturbed me was that after so many people had climbed up the same shallow footholds, a lot of slippery mud was left on them; I was wearing European rubber-soled shoes while slip easily and this made it difficult to get a grip on the narrow footholds. However, I did not find it as hard as I expected.

When I reached the top of this hazardous ascent I found myself on a very narrow ledge with a sheer drop beneath it. I asked the porters, “What do I do next?” They told me that there was a long ladder from the ledge going down to a rock in the middle of the river; from this rock there was a line of bridges made of pine trunks which crossed a series of rocks to the farther bank. The porter looked very cheerful and said, “It’s only a ladder; just follow me.” I was still roped to the two porters. When I got on the ladder I saw how immensely long it was; we seemed to be so high up that a man at the bottom looked like a mere dwarf. It was made of single pine trunks lashed together from end to end, with notches cut in the wood for footholds. When I climbed down the first few notches I could see the swirling green waters of the river underneath; a few more steps, and I felt I was poised in space over an expanse of water. There was a cold wind coming up from a large cave under the rock into which the river was pouring; worst of all, the ladder shook in a terrifying way with the weight of the many porters who were there trying to help me. All our party who had reached the bottom of the ladder stopped to watch me. I was told that the porters had had great difficulties with some of the older men, who had been so frightened that they had nearly fainted. There was great rejoicing when I rejoined them at the bottom. When we reached the dry land we pitched camp and from here we could see the ladder and the ledge some hundred feet higher up. Next day’s track proved to be no better than the last; no part of it was on the level and we had continually to climb up cliff faces more than a thousand feet high, sometimes only by footholds cut in the rock. However, after our first experience these held no terrors for us. In places we had to make up the roadway itself because, since the Chinese had come into Tibet, this route had been little used and much of it had been disturbed by the earthquake of 1950 which had been especially severe in this region. I was getting more acclimatized to walking and sleeping under these rough conditions.

The perilous route to Rigong Kha

.

The porter whom we had sent ahead to Rigong Kha returned with a local man to welcome us to his village. He told us that there were no Chinese in Rigong Kha, though they were farther eastward in the valley; however, there were strong Resistance forces in Upper Powo who believed that they could push the Communists back.

Kino Tulku had been too energetic, the very heavy loads which he had chosen to carry were beyond his strength and his eyesight became affected. We feared it was a blood clot; however, there was nowhere on the track where we could stop, so the most important thing was to get him to the village as soon as possible. From where we were we could see small farms in the distance, but there was still a long way to walk and it was all uphill. There were very few streams and we found the going very exhausting without any water to drink. When we came to a field about half a mile from Rigong Kha we stopped for the night and some of our party went up to the village to buy food. They found most of the villagers very friendly. Kino Tulku’s eyes had been growing steadily worse and the whole camp was very worried as we thought this might affect our plans. The following day a number of the villagers came to visit us. They were very surprised at finding so large a party and could not conceal their curiosity, for they had never met people from East Tibet other than a few pilgrims; no other refugees had come this way. In this isolated village the inhabitants had never seen horses, mules, or yaks, their only domestic animals being small buffaloes and pigs. Their dialect was a mixture of Kongpo and Powo and they wore the Kongpo dress, which for the men was the ordinary

chuba

(gown) made of woolen cloth worn under a long straight garment made of goatskin with the hair on the outside. These were belted at the waist and cut open in the middle to slip over the head. The women’s chubas were also of wool; they wore caps edged with gold brocade and they all carried a good deal of jewelry, chiefly in the form of earrings or necklaces; their boots were embroidered in bright colors.

The climb up to the village was easy and the people there gave us a warm welcome. We were a little afraid lest some traveler coming from the eastern side might turn out to be a spy, but actually there was no need for anxiety on this score. The villagers had had no authentic news of happenings at Lhasa; some vague rumors had reached them through the Communists in the lower part of the valley: When we assured them that the Communists had taken control in Lhasa and that the Dalai Lama had escaped to India, they still would not believe it. Traders coming to Rigong Kha brought the news that though the Resistance forces had fought very bravely in the Tong Gyuk Valley and had at first held the bridge, the Communists had finally gained possession of it. Now, all the area as far as Chamdo was in Communist hands; they had rebuilt the road from Chengtu in Szechuan to Chamdo and their troops were everywhere. In all the districts they had started to form rigorous indoctrination groups. It was now certain that they would penetrate before long into the Tong Gyuk Valley, barring our further route along it, so we were obliged to revise all our ideas on the subject of the best route to follow. Up till then we had been hoping to follow the Yigong River to where it joins the Brahmaputra, almost at the point where that great river turns down toward India. There was nothing to be done but to find another way. We asked the villagers if they knew of any other route by which we could cross the military highway the Chinese had constructed, but though they supposed that there might be some tracks across the mountain ranges, they really had no idea how we could get through to Lower Kongpo. Some people suggested that we might join forces with the Potö Resistance group, but they were some distance away and in any case we were not bent on fighting.