The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 (46 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Three: 3 Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

You might say that certain people approach the path from more positive inspirations. They might have had a dream or a vision or an insight that inspired them to search more deeply. Possibly they had money to fly to India or the charm and courage to hitchhike there. Then they had all sorts of exotic and exciting experiences. Someone stuck in New York City might consider it a rich and heroic journey. But fundamentally such people still have the mentality of poverty. Although their initial inspiration may have been expansive, still they are uncertain about how to relate to the teachings. They feel that the teachings are too precious, too rich for them to digest. They doubt whether they can master a spiritual discipline. The more inadequate they feel, the more devoted they become. Fundamentally, such devotion involves valuing the object of devotion. The poorer you feel, the richer the guru seems by contrast. As the seeming gap between what he has and what you have grows, your devotion grows as well. You are more willing to give something to your guru.

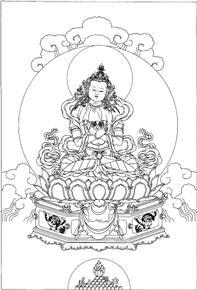

Vajradhara. The Buddha manifests himself as Vajradhara to expound the teachings of tantra. He is also the supreme buddha expressing the whole of existence as unborn and unoriginated. The tantric practitioner’s personal teacher is identified with Vajradhara. He is the source of several important lineages of Buddhism in Tibet.

DRAWING BY GLEN EDDY.

But what do you want in return? That is the problem. “I want to be saved from pain, my misery, my problems. I would like to be saved so that I might be happy. I want to feel glorious, fantastic, good, creative. I want to be like my guru. I want to incorporate his admirable qualities into my personality. I want to enrich my ego. I want to get some new information into my system so that I might handle myself better.” But this is like asking for a transplant of some kind. “Maybe the Heart of the Great Wisdom could be transplanted into my chest. Perhaps I could exchange my brain.” Before we wholeheartedly give ourselves to serving a guru we should be very suspicious of why we are doing it. What are we looking for, really?

You may approach a spiritual friend and declare your intention to surrender to him. “I am dedicated to your cause, which I love very much. I love you and your teachings. Where do I sign my name? Is there a dotted line that I could sign on?” But the spiritual friend has none—no dotted line. You feel uncomfortable. “If it is an organization, why don’t they have a place for me to sign my name, some way to acknowledge that I have joined them? They have discipline, morality, a philosophy but no place for me to sign my name.” “As far as this organization is concerned, we do not care what your name is. Your commitment is more important than putting down your name.” You might feel disturbed that you will not get some form of credentials. “Sorry, we don’t need your name or address or telephone number. Just come and practice.”

This is the starting point of devotion—trusting a situation in which you do not have an ID card, in which there is no room for credits or acknowledgment. Just give in. Why do we have to know who gave in? The giver needs no name, no credentials. Everybody jumps into a gigantic cauldron. It does not matter how or when you jump into it, but sooner or later you must. The water is boiling, the fire is kept going. You become part of a huge stew. The starting point of devotion is to dismantle your credentials. You need discoloring, depersonalizing of your individuality. The purpose of surrender is to make everyone gray—no white, no blue—pure gray. The teaching demands that everyone be thrown into the big cauldron of soup. You cannot stick your neck out and say, “I’m an onion, therefore I should be more smelly.” “Get down, you’re just another vegetable.” “I’m a carrot, isn’t my orange color noticeable?” “No, you are still orange only because we haven’t boiled you long enough.”

At this point you might say to yourself, “He’s warning me to be very suspicious of how I approach the spiritual path, but what about questioning him? How do I know that what he is saying is true?” You don’t. There is no insurance policy. In fact, there is much reason to be highly suspicious of me. You never met Buddha. You have only read books that others have written about what he said. Assuming that Buddha knew what was true, which of course is itself open to question, we do not know whether his message was transmitted correctly and completely from generation to generation. Perhaps someone misunderstood and twisted it. And the message we receive is subtly but fundamentally wrong. How do we know that what we are hearing is actually trustworthy? Perhaps we are wasting our time or being misled. Perhaps we are involved in a fraud. There is no answer to such doubts, no authority that can be trusted. Ultimately, we can trust only in our own basic intelligence.

Since you are at least considering the possibility of trusting what I am saying, I will go on to suggest certain guidelines for determining whether your relationship with a teacher is genuine. Your first impulse might be to look for a one hundred percent enlightened being, someone who is recognized by the authorities, who is famous, who seems to have helped people we know. The trouble with that approach is that it is very difficult to understand what qualities an enlightened being would have. We have preconceptions as to what they are, but do they correspond to reality? Selecting a spiritual friend should be based upon our personal experience of communication with this person, rather than upon whether or not the person fits our preconceptions. Proper transmission requires intimate friendship, direct contact with the spiritual friend. If we see the guru as someone who possesses higher, superior knowledge, who is greater than us, who is extremely compassionate to actually pay attention to us, then transmission is blocked. If we feel that we are a miserable little person who is being given a golden cup, then we are overwhelmed by the gift, we do not know what to do with it. Our gift becomes a burden because our relationship is awkward and heavy.

In the case of genuine friendship between teacher and student there is direct and total communication which is called “the meeting of the two minds.” The teacher opens and you open; both of you are in the same space. In order for you to make friends with a teacher in a complete sense, he has to know what you are and how you are. Revealing that is surrendering. If your movements are clumsy or if your hands are dirty when you shake hands, you should not be ashamed of it. Just present yourself as you are. Surrendering is presenting a complete psychological portrait of yourself to your friend, including all your negative, neurotic traits. The point of meeting with the teacher is not to impress him so that he will give you something, but the point is just to present what you are. It is similar to a physician-patient relationship. You must tell your doctor what is wrong with you, what symptoms you have. If you tell him all your symptoms, then he can help you as much as possible. Whereas if you try to hide your illness, try to impress him with how healthy you are, how little attention you need, then naturally you are not going to receive much help. So to begin with devotion means to be what you are, to share yourself with a spiritual friend.

S

PIRITUAL

F

RIEND

In the hinayana Buddhist approach to devotion you are confused and need to relate to a model of sanity, to a sensible human being who, because of his disciplined practice and study, sees the world clearly. It is as if you are flipping in and out of hallucinations, so you seek out someone who can distinguish for you what is real and what is illusion. In that sense the person you seek must be like a parent educating a child. But he is the kind of parent who is open to communicate with you. And like a parent, he seems to be an ordinary human being who grew up experiencing difficulties, who shares your concerns and your common physical needs. The hinayanists view Buddha as an ordinary human being, a son of man who through great perseverance attained enlightenment but who still had a body and could still share our common human experience.

In contrast to the hinayana view of the teacher as a parental figure, the mahayanists view the teacher as a spiritual friend—

kalyanamitra

in Sanskrit—which literally means “spiritual friend” or “companion in the virtue.” Virtue, as it is used here, is inherent richness, rich soil fertilized by the rotting manure of neurosis. You have tremendous potential, you are ripe, you smell like one-hundred-percent ripe blue cheese, which can be smelled miles away. Devotion is the acknowledging of that potential by both the teacher and the student. The student is like an adolescent who obviously has great potential talents but who does not know the ways of the world. He needs a master to teach him what to do, how to develop his talent. He is always making mistakes due to his inexperience and needs close supervision. At the mahayana level the spiritual friend seems to possess much more power and understanding than you. He has mastered all kinds of disciplines and techniques and knows how to handle situations extraordinarily well. He is like a highly skilled physician who can prescribe the right remedies for your frequent spiritual illnesses, your continual blundering.

At the mahayana level you are not as bothered by trying to make sure your world is real: “At last I’ve found solid ground, a solid footing. I have discovered the meaning of reality.” We begin to relax and feel comfortable. We have found out what is edible. But how do we eat? Do we eat everything at once, without discrimination? We could get a stomach upset if we combine our foods improperly. We have to open ourselves to the suggestions of the spiritual friend at this point; he begins to mind our business a great deal. At first he may be kind and gentle with us, but nevertheless there is no privacy from him; every corner is being watched. The more we try to hide, the more our disguises are penetrated. It is not necessarily because the teacher is extremely awake or a mind reader. Rather our paranoia about impressing him or hiding from him makes our neurosis more transparent. The covering itself is transparent. The teacher acts as a mirror, which we find irritating and discomforting. It may seem at that point that the teacher is not trying to help you at all but is deliberately being provocative, even sadistic. But such overwhelming openness is real friendship.

This friendship involves a youthful and challenging relationship in which the spiritual friend is your lover. Conventionally, a lover means someone who relates with your physical passion and makes love to you and acknowledges you in that way. Another type of lover admires you generally. He would not necessarily make love to you physically, but would acknowledge or understand your beauty, your flair, your glamorousness. In the case of the spiritual friend, he is your lover in the sense that he wants to communicate with your grotesqueness as well as your beauty. Such communication is very dangerous and painful. We are unclear how to relate to it.

Such a spiritual friend is outrageously unreasonable simply because he minds your business so relentlessly. He is concerned about how you say hello, how you handle yourself coming into the room, and so on. You want him to get out of your territory, he is too much. “Don’t play games with me when I’m weak and vulnerable.” Even if you see him when you feel strong, then you usually want him to recognize your strength, which is another vulnerability. You are looking for feedback in either case. He seems invulnerable and you feel threatened. He is like a beautifully built train coming toward you on solid tracks; there is no way to stop him. Or he is like an antique sword with a razor-sharp edge about to strike you. The heavy-handedness of the spiritual friend is both appreciated and highly irritating. His style is extremely forceful but so together, so right that you cannot challenge it. That is devotion. You admire his style so much, but you feel terrified by it. It is beautiful but it is going to crush you, cut you to pieces. Devotion in this case involves so much sharpness that you cannot even plead for mercy by claiming to be a wretched, nice little person who is devoted and prostrates to his teacher all the time and kisses his feet. Conmanship is ineffective in such a situation. The whole thing is very heavy-handed. The real function of a spiritual friend is to insult you.

T

HE

G

REAT

W

ARRIOR

As you advanced to the mahayana path, the spiritual friend was like a physician. At first your relationship was sympathetic, friendly, predictable. When you visited your friend he would always sit in the same chair and you would always be served the same kind of tea. The spiritual friend would do everything precisely and everything had to be done for him precisely; if you were imprecise he would caution you. Or you might have a friend who did all kinds of crazy things, but that style was also predictable. You might even expect that he would challenge you if you acted too predictably. In either case, you were afraid of the guru changing his style, of becoming truly unpredictable. You preferred to maintain the smooth, beautiful, peaceful style of communication. You were very comfortable and could trust the situation, devote yourself wholeheartedly to it, absorb yourself in it, as though you were watching a railroad train whose wheels go round and round, chug, chug, always predictable. You knew when the train would reach the station. You knew when it would leave again—chug, chug, chug—always predictable. You hoped that your friend would always be kind and noble with you.