The Colosseum

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

‘A racy and occasionally confrontational book … revels in the accretions of detail and myth … first-class scholarship and an engagingly demotic style’ Michael Bywater,

Independent

‘A rollicking good read … the authors’ lively style does full justice to their rumbustious subject matter’

Guardian

‘The authors wear their eclectic learning lightly … exemplary prose … quiet, confident and thorough, this is a fine English book in the best sense of the word’

The Times

‘A work of scholarship written with the general reader in mind … a pleasure to read’

Spectator

‘Supported by an impeccably marshalled but never obtrusive evidential base … beautifully written and highly readable’

Times Higher Education Supplement

‘The authors’ educated guesses tend to be more fascinating than the familiar Hollywood portrayal … it enriches our appreciation of the Colosseum’s magnitude and significance’

Independent on Sunday

‘This is a volume to take on any journey; it will tell you as much about the perception of ruins as it does about Rome itself’

BBC History Magazine

‘This lively book carries the reader painlessly through a complex record of legend and history. A delightful and instructive account’ G. W. Bowerstock, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton

‘A splendid monograph’

Irish Catholic

‘Anecdotal, lively and enlightening, Hopkins and Beard’s book is hugely worthwhile’

Italian

‘A small gem of a book … the most engaging and entertaining biography of the site available’

Minerva

‘This lively, engaging and scholarly book brilliantly conveys the complex significance of this potent monument and of the spectacles that took place within it’

Royal Academy Magazine

KEITH HOPKINS

was Professor of Ancient History at the University of Cambridge and Vice-Provost of King’s College. He was one of the most radical re-interpreters of Roman history and culture of the last fifty years, and author of

Conquerors and Slaves

(1978),

Death and Renewal

(1983) and

A World Full of Gods

(1999). He died in 2004.

MARY BEARD

is a Professor of Classics at Cambridge and a Fellow of Newnham College. She is general editor of the Wonders of the World series and has written widely on classical culture and its reception in the contemporary world. Her books include

Classical Art from Greece to Rome

with J. Henderson (Oxford, 2001),

The Roman Triumph

(Harvard, 2007),

Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town

(Profile, 2008),

It’s a Don’s Life

(Profile, 2009), and

The Parthenon

(Profile, 2010).

WONDERS OF THE WORLD

THE COLOSSEUM

KEITH HOPKINS

AND

MARY BEARD

This updated paperback edition published in 2011

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by

Profile Books Ltd

3

A

Exmouth House

Pine Street

Exmouth Market

London

ECIR OJH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard, 2005, 2006, 2011

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Caslon by MacGuru Ltd

[email protected]

Designed by Peter Campbell

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the authors has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 470 8

eISBN 978 1 84765 045 0

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

4

The People of the Colosseum

PREFACE

The Colosseum is the most famous, and instantly recognisable, monument to have survived from the classical world. So famous, in fact, that for over seventy years, from 1928 to 2000, a fragment of its distinctive colonnade was displayed on the medals awarded to victorious athletes at the Olympic Games – as a symbol of classicism and of the modern Games’ ancient ancestor.

It was not until the Sydney Games in 2000 that this caused any controversy. British newspapers – most of which did not know that the Colosseum had been gracing Olympic medals for more than half a century – enjoyed poking fun at the ignorance of the antipodeans who apparently had not grasped the simple fact that the Colosseum was Roman and the Games were Greek. The Australian–Greek press took a loftier tone; as one Greek editor thundered, ‘The Colosseum is a stadium of blood. It has nothing to do with the Olympic ideals of peace and brotherhood.’

The International Olympic Committee wriggled slightly, but stood their ground. They had already prevented the organisers of the Games replacing the Colosseum with the profile of the Sydney Opera House, so they presumably had their arguments ready. The design, they insisted, was traditional and it was not, in any case, the Roman Colosseum specifically, but rather a ‘generic’ Colosseum: ‘As far as we are concerned, it’s not important if it’s the Colosseum or the Parthenon. What’s important is that it’s a stadium.’

1. The Sydney Olympic medal (2000) displays the distinctive form of the Colosseum behind the Goddess of Victory and a racing chariot. ‘The Ultimate Ignorance’ complained one Greek newspaper in Australia.

Unsurprisingly, the Colosseum motif had been replaced by the time the Games went (back) to Greece in 2004. The ponderously titled ‘Committee to Change the Design of the Olympic Medal’ came up with a new, Greek and much less instantly recognisable design: a figure of Victory flying over the Panathinaikon stadium built in Athens to host the first modern Games in 1896. But the questions that this argument raised about the Colosseum itself still remain. What was its original purpose? (Certainly not the racing signalled by the miniature chariot also depicted on the medal.) How should we now respond to the bloody combats of gladiators that have come to define its image in modern culture? Why is it such a famous monument?

These are just some of the questions we set out to answer in this book.

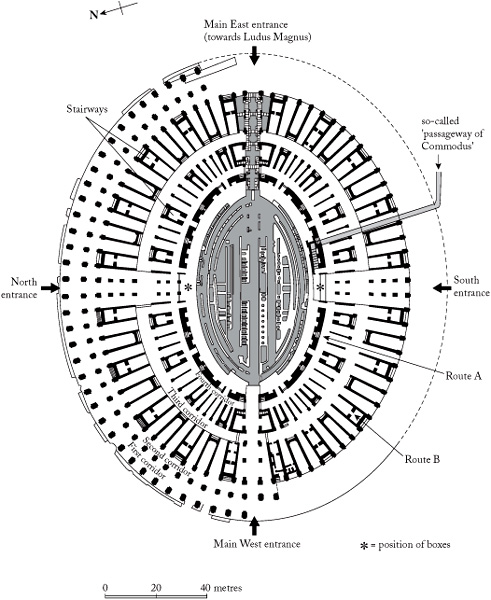

Figure 1. Plan of the Colosseum.

1

THE COLOSSEUM NOW …

COLOSSEUM BY MOONLIGHT

In 1843 the first edition of

Murray’s Handbook to Central Italy

, the essential pocketbook companion for the well-heeled Victorian tourist, enthusiastically recommended a visit to the Colosseum (or the ‘Coliseum’ as it was then regularly spelled). Many aspects of Rome, it warned, would prove inconvenient or disappointing. The Roman system of timekeeping was simply baffling for the punctual British visitor; its twenty-four-hour clock began an hour and a half after sunset, so times changed with the seasons. The local cuisine left a lot to be desired (‘A good restaurateur is still one of the

desiderata

of Rome’, moaned the

Handbook

, somewhat sniffily). Accommodation too could be difficult to find, especially for those with special requirements – the invalids who were recommended to search out rooms with ‘a southern aspect’, or the ‘nervous persons’ advised to ‘live in more open and elevated situations’. Yet the Colosseum was guaranteed not to disappoint. In fact, it was even more impressive in real life than its reputation might suggest: ‘There is no monument of ancient Rome which artists and engravers have made so familiar to readers of all classes … and there is certainly none of which the descriptions and drawings are so far surpassed by the reality.’ No need then to promote its virtues

or guide the visitor’s response. ‘We shall not attempt to anticipate the feelings of the traveller,’ the

Handbook

continued, ‘or obtrude upon him a single word which may interfere with his own impressions, but simply supply him with such facts as may be useful in his examination of the ruin.’

A brisk account followed, with plenty of dry dates, dimensions and figures. Building work started under the emperor Vespasian in

AD

72, with the opening ceremonies under his son Titus in 80; the last recorded wild beast show in the arena took place in the reign of Theodoric (who died in

AD

526) – unless you count a bull-fight staged in 1332. The whole structure covered some 6 acres and was built of travertine stone (mixed with brick in the interior). Its outer elevation comprised four storeys, to a total of 157 English feet, with eighty arches on the ground floor giving an entrance to seats and arena. Inside, the arena measured 278 by 177 feet and was originally surrounded by seating in four separate tiers which could accommodate, according to one late Roman description, 87,000 spectators. And so on. But, in traditional guidebook style, the pill of these facts and figures was sugared by the occasional curious myth, anecdote or arcane piece of knowledge. Hence the reference to a story put about by the Church, in a fit of wishful thinking, that the architect of the Colosseum had actually been a Christian and a martyr by the name of Gaudentius; and hence the account of the plans of Pope Sixtus V in the sixteenth century to convert the whole building into a wool factory, with shops in the arcades – a scheme which, even though abandoned, came at enormous financial cost to the pontiff. There were also misconceptions to be corrected. Those puzzling little holes all over the building were not, as many people had said,

where poles had been inserted to support the booths erected for the medieval fairs that took place there. They were instead (and this is still thought to be the correct explanation) where enterprising medieval hucksters had dug into the structure to remove and make off with the iron clamps which held the blocks together.

Helpful hints were offered too on how to make the most of a visit. The important thing, then as now, was to get as high up on the building as possible. For the Victorian visitor, a special staircase had been constructed to give access to the upper storeys ‘and thence as high as the parapet’. From here, where there was a view both into the Colosseum itself and out over such notable antiquities as the Arch of Constantine, the Palatine Hill and the Roman Forum, ‘the scene … is one of the most impressive in the world’. If this might seem perilously close to an ‘attempt to anticipate the feelings of the traveller’, then even more so was the insistence that the view was best at night, by the light of the moon. ‘There are few travellers who do not visit this spot by moonlight in order to realise the magnificent description in “Manfred”, the only description which has ever done justice to the wonders of the Coliseum.’ As if to underline the point, and to tell the visitor exactly how to react, a substantial chunk of Lord Byron’s ‘Manfred’ was quoted, with its famous comparison of the night-time impact of the standing – albeit ruined – Colosseum (‘the gladiators’ bloody Circus’) and the paltry and overgrown remains of what had once been the palace of the Roman emperors (‘Caesar’s chambers, and the Augustan halls’) on the Palatine: