The Colosseum (9 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

12. A pristine helmet from the gladiatorial barracks at Pompeii, displaying figures of the Muses. On the right perhaps Euterpe, with a wind instrument in her right hand; next to her Urania – holding a globe suggesting her connection with astronomy.

Some archaeologists, predictably, have tried very hard to resist that suspicion, and have resorted to some desperate arguments in the process. Maybe this Pompeian armour was a new consignment, not yet knocked around in the arena. Maybe the short length of the gladiatorial bouts meant that such weight of equipment was manageable for these fit men; it was not, after all, like fighting a day-long legionary battle. Maybe – and this is where desperation passes the bounds of plausibility – the helmets were known to be so strong that no canny opponent would have bothered to take aim at them, hence their apparently pristine state. Maybe. But much more likely is that this armour was the display collection, used only perhaps when the gladiators paraded into the arena at the start of the show (to be replaced by more practical equipment as soon as the fighting started), or on other ceremonial occasions. It was the also the kind of equipment that would best symbolise the gladiator on funeral images or other works of art. Our guess is that what the spectator would actually have seen in the Colosseum or any amphitheatre was probably much less like the figure re-invented by Gérôme (who almost certainly had seen the Pompeian finds), and much more like the more lightly clad, though still recognisably ‘gladiatorial’, gladiators envisaged by de Chirico in the 1920s and the rather more nifty fighters depicted in the casual graffiti from Pompeii (illustrations 13 and 14). There is little reason to think that the gladiators regularly lumbered around the arena in their display kit (which would certainly have allowed no Russell Crowe-style balletics). Perhaps no more reason than to imagine that British university students regularly wear on campus the mortar boards, gowns and imitation fur in which they are dressed for those ceremonial graduation photographs, treasured in their parents’ photo albums.

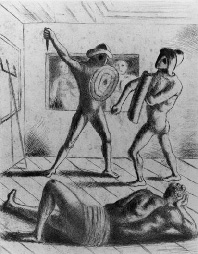

13. De Chirico’s near naked gladiators (1928) hint at an eroticised image of gladiatorial power and allure.

But what, finally, of the standard programme of displays in the amphitheatre: animal hunts in the morning, executions at midday, gladiators in the afternoon (with the public gladiatorial dinner the evening before to allow the punters to study form)? It is quite true that each of these elements is referred to by ancient writers describing the shows. The question is whether or not it is right to stitch all these references together into a ‘programme’. This is a trap modern students of Roman culture often fall into: pick up one reference in a letter written in the first century

AD

, combine it with a casual aside in a historian writing a hundred years later, a joke by a Roman satirist which seems to be referring to the same phenomenon, plus a head-on attack composed by a Christian propagandist in North Africa; add it all together and – hey, presto! – you’ve made a picture, reconstructed an institution of ancient Rome. It is exactly this kind of historical procedure which lies behind modern views of what happened at a Roman bath or at the races in the Circus Maximus, or at almost any Roman religious ritual you care to name. And it lies behind most attempts to reconstruct the shows in the amphitheatre too.

Why is it usually assumed that the lunch interlude was the time for executions? Because the philosopher Seneca writing in the mid first century

AD

, before the Colosseum was built, in a letter concerned with the moral dangers of crowds, complains that the midday spectacles in some shows he had attended were even worse than the morning. ‘In the morning men were thrown to lions and bears, at noon to the audience,’ he quips. And he goes on to deplore the unadulterated cruelty, while explaining that its victims are criminals – robbers and murderers. That is the only evidence for the lunchtime executions (apart perhaps from a passing reference to ‘the ludicrous cruelties of midday’ in Tertullian’s Christian attack on Roman spectacles). In fact, there is just as much evidence for some kind of burlesque or comedy interlude at lunchtime. And that may have been what Seneca was expecting, when he writes that he was hoping for some ‘wit and humour’.

14. These graffiti from Pompeii tell the story of three fights that took place at the nearby town of Nola. In the first a veteran Hilarus wins (‘v’ for ‘

vicit

’) against a fighter who is nevertheless let off with his life (‘m’, ‘

missus

’ meaning ‘discharged’). Below a new boy, Marcus Attilius (‘t’ for ‘

tiro

’ or novice) defeats first Hilarus, then Lucius Raecius Felix (both of whom are spared, ‘

missi

’).

Why is it believed that gladiators regularly had a public meal the night before their show? Because a couple of Christian martyrs in the arena at Carthage in

AD

203 were given ‘a last supper which is called a “free supper”’; because Tertullian again, rather puzzlingly, claims that he himself does not recline in public ‘like beast fighters taking their last meal’; and because Plutarch writing at the turn of the first and second centuries

AD

claims that although gladiators are offered expensive food before their shows, they are more interested (understandably we might think) in making arrangements for their wives and slaves. Maybe that is enough evidence to suggest a regular public, pre-show banquet; maybe not. There is certainly no evidence at all for the punters coming along to study form; in fact, we have no direct evidence at all for widespread betting on the results of this fighting. That is an idea that comes mostly from the imagination of modern historians, trying to make sense of the shows by assimilating them to horse racing, or to ancient chariot racing, which certainly did attract gambling.

Of course, the success of public spectacle depends, in part, on the audience having a general idea of what is going to happen. In that sense there must have been some shared foreknowledge of what was likely to be involved in shows in the amphitheatre: animal hunts, executions, gladiators, plus (on a very lucky day) more adventurous displays such as those mock naval battles. Certainly there is a quite a lot of evidence for the animal hunts often being scheduled in the morning (it might have been easier to keep the gladiators hanging around than the animals); and casual references to ‘the morning shows’ do usually seem to refer to the hunts and other animal displays. But success also depends on novelty and surprise. We must reckon that, rather than the rigid order of ceremonies often assumed, the performances at the Colosseum varied enormously according to the ingenuity of the presenter, the amount of money at his disposal, the practical availability of beasts, criminals or gladiators. After all, a hundred days of spectacles with executions each lunchtime would surely have soon exhausted the supply of condemned men and women, even in a society as brutal and cruel as Rome. These games must have been the same

and different

each time.

The Colosseum and its shows are the most familiar part of ancient Roman culture in the modern world. Films and novels, as well as serious scholarly accounts, present to us a relatively consistent picture of the performances in the amphitheatres. At the same time as we puzzle at the cruelty and the bloodshed involved, at

why

they did it, we feel relatively confident that we know roughly

what

it was they did.

Most readers will be able to close their eyes and conjure an image of the Colosseum in full swing. That is why it is such an important monument in the history of modern engagement with ancient Rome. This chapter has tried to suggest that some of that confidence is ill placed. It is much harder than we often imagine accurately to recreate the scene in the killing fields of the Colosseum; still harder (as the extraordinary series of poems by Martial prompts us to reflect) even to begin to understand what it was the Romans themselves saw in this slaughter.

But happily, looking closer at the Colosseum is not only a matter of discovering that we know less than we thought. The next chapter will turn a shrewd eye towards some of the Colosseum’s cast of characters: from the gladiators again, through the lions to the emperor and audience, and to what we can tell of their reactions to what they witnessed. Of course, these were only part of the cast list. Apart from a handful of references on tombstones and other inscriptions to slaves and ex-slaves who looked after the costumes or guarded the gladiators’ weapon store, the vast slave battalions who serviced the building and its entertainments, the cleaners and gate-keepers, the wardrobe-mistresses and the odd-job men, are now completely (in the old catch-phrase) ‘hidden from history’. Nonetheless, if we change the focus of inquiry slightly and ask rather different questions of the evidence we have, we discover that we know more than we thought rather than less.

4

THE PEOPLE OF THE COLOSSEUM

‘HEART-THROBS OF THE GIRLS’?

Gladiators were marginal outsiders in Roman society. Some of them literally so: captives of war, the poor and destitute who saw in possible success in the arena their only (desperate) hope, slaves sold to the gladiatorial ‘training camps’ (in Latin

ludi

, usually rather too domestically translated as ‘schools’), condemned men sent there as punishment. They were, in fact, almost exclusively men. Apart from a few exceptional and usually scandalous cases – such as the emperor Nero’s reputed display of an entirely black troupe of gladiators, women and children included – female gladiators are more a feature of modern over-optimistic fantasy than Roman practice. The body of a Roman woman found in London in 2000 and eagerly identified as a female gladiator, on the basis of some lamps found with her carrying gladiatorial scenes, was probably nothing of the kind but just an ‘ordinary’ woman buried with her favourite trinkets, if anything a fan rather than a contestant.

A gladiator’s life was dangerous, painful and probably short – even if for the skilled or lucky few success might bring rewards and eventually discharge. It is significant that

the most famous doctor of the Roman world, Galen, who ended up as the court physician to the second-century emperor Marcus Aurelius, started his career treating gladiators in Pergamum (in modern Turkey). He claims to have found the experience useful in his studies of human anatomy and various therapeutic methods and regimes, and he drew on it in writing his voluminous medical treatises. When we read his account of the problems of replacing intestines hanging out through a gaping wound, we are probably getting close to some of the real-life gladiatorial experience in the arena. The simple presence of a doctor, however, hints at the economic interests that may have mitigated the physical conditions experienced by most of the fighters. A dead gladiator was an expensive gladiator. Likewise mangy specimens were probably no crowd-pullers. Their living quarters, clothing and rations must have varied enormously through the many different troupes and camps in the empire: some were small private-enterprise affairs (much like that of the gladiatorial impresario Proximo, played by Oliver Reed, in

Gladiator

); others were effectively part of the imperial state organisation in Rome itself, located conveniently close to the Colosseum. But, wherever they were based, logic suggests that they would not have been kept in starvation. Some Roman writers refer to standard gladiatorial fare as ‘

sagina

’, ‘stuffing’ – a characteristically snobbish disdain for humble food, and at the same time hinting unpleasantly at the similarity of the fighters to dead animals. But coarse diet or not, it would probably have been eyed enviously by large sections of the Roman poor.