The Colosseum (15 page)

Authors: Keith Hopkins,Mary Beard

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General, #Travel

It is out of the question for someone in the early twentyfirst century not to deplore the slaughter of the arena. In antiquity intense enthusiasm for the shows went hand in hand with a whole range of rather different ethical doubts (and snobbish expressions of disdain). Both philosophers and theologians questioned the effect on the audience of watching the bloodshed. Did it, as some argued, damage the capacity for rational thought? What was the effect on the human mind and character? St Augustine writes memorably in his

Confessions

of one Alypius, who was eventually to become a Christian bishop, going unwillingly to some shows with his friends. Though determined to keep his eyes shut, as soon as he peeped he was hooked. The spectacle had done its work:

‘when he saw the blood, it was as though he had drunk deeply on savage passion’. Others wondered about the moral differences in shows involving different legal categories of victim: killing criminals was one thing, killing Roman citizens quite another. Of course, these are not our own objections; nor, in pagan antiquity at least, do they amount to anything approaching a campaign for the abolition of the shows. That said, they show the Romans thinking rather harder about these spectacles than their popular image would have it.

We have already in this chapter wondered whether the shows in the Colosseum were always quite the extravagant displays that they are painted; whether the roaring crowd did always fill every vacant seat (as the digital technology of

Gladiator

made it). We end it by wondering whether the crowd – different in their reactions as they must be from us – were quite the conscience-free and murderous enthusiasts for indiscriminate killing that it is convenient for us to imagine. True, in our terms, they were horribly cruel. Their ethical boundaries were drawn in very different places from our own; but that does not mean they had no ethical boundaries, or ethical doubts, at all.

5

BRICKS AND MORTAR

THE ORIGINAL COLOSSEUM?

It is a well-known axiom among archaeologists that the more famous a monument is, the less likely any of its original structures are to survive – the more likely it is to have been restored, rebuilt and, more or less imaginatively, reconstructed. There is an inverse correlation, in other words, between fame and ‘authenticity’ in the strictest sense. The Colosseum is a classic instance of this rule. A large proportion of what you see when you visit is much later than the original work of Vespasian and Titus in the 70s

AD

. The puzzle of dating the individual parts and the different phases has kept archaeologists amused for centuries. The truth is, though, that – despite the confident assertions of most guidebooks – it is now impossible in many cases to be certain which bits were built when. The usual euphemism that the ‘skeleton’ of the building is still essentially in its original form may be true enough, but it glosses over the question of how much of the building counts as the skeleton.

The monument has suffered all kinds of damage – from fire, earthquake and other natural and man-made disasters – throughout its history. There are records of repairs up to perhaps as late as the early sixth century

AD

, commemorated

in inscriptions that have been discovered in the building (the latest one documents the restoration of ‘the arena and the podium, which had collapsed in an abominable earthquake’). A particularly devastating blaze in 217 is described by Dio, who claims that the ‘hunting theatre was struck by lightning … and such a conflagration followed that the whole of the upper circuit and every thing in the arena was consumed; and then the rest was ravaged by the flames and dismantled’. The building was, according to Dio, out of use for many years. But even with this clear testimony, it has proved difficult to identify exactly the third-century repairs or their extent. The most recent attempt has concluded that the damage was more limited than Dio implies, but at the same time has suggested that one section of the main outer wall of the building, usually taken to be part of the original first-century construction, actually dates from the rebuild in the third century.

The problem is that dating Roman brickwork and masonry is a tricky art. Some Roman bricks were stamped with makers’ marks in the course of their production and these ‘brick-stamps’ can give (or allow one to deduce) an exact date. Yet, even so, it is often hard to tell whether the dated brick is part of a small repair or the main phase of construction – or even whether an old brick has been used to patch up damage centuries later. And not just in the ancient world itself. The Colosseum has continued to be repaired and adapted ever since. Some of this work used material indistinguishable from that used by Romans or, even more often, reused Roman material that was lying about the site. It is now not always possible, even for experts (though few like to admit it), to tell an eighteenth-century insertion from a fourth-century one. Of course, this sense that the monument

is a patchwork of many centuries gives it much of its charm. But it also makes it hard to trace the details of its history.

The other main problem in reconstructing the original monument – whether as it stood at its inauguration in

AD

80 or at any later period in the Roman empire – is the simple fact that so much of it has disappeared. True, its silhouette remains a magnificent and imposing presence in the Roman city-scape, and it is especially impressive from the air flying into the airport at Ciampino from the north (sit on the righthand side of the plane). But about two-thirds of its ancient fabric has gone, most of that, as we shall see in

Chapter 6

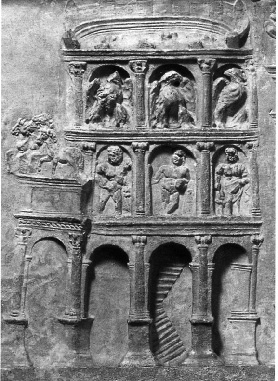

, rifled in later periods to provide the building material for medieval and renaissance Rome. Large sections of the building as it now stands are not ancient at all, but the result of restoration over the last two centuries. Outside, half the outer wall has been destroyed; inside, there is no arena floor and no seats survive (the small reconstructed section of seating on the north-east side is a fantasy of the 1930s and gives a misleading impression of the original layout – illustration 20). Besides, the stark, almost industrial, character of the monument today is the result of the loss of almost all of its marble facings, its rich paintings and stuccoes, and the statues that once decorated the exterior arches. A relief sculpture of the Colosseum from a first-century Roman tomb gives a quite different, and probably more accurate, impression of the decorative excess of the building in its original state (illustration 21).

Nonetheless, there is still a lot to be learned from a careful look at the surviving remains. The archaeology of the building in some important respects enriches our understanding of what went on there. Equally the accounts of the shows, the gladiators and the animal hunts we have already discussed help to make sense of the tantalising ruin that is the Colosseum today.

20. The only reconstructed seating in the Colosseum is some wishful thinking of the 1930s. Also visible (bottom left) is the modern wooden flooring over part of the arena. What appears to be the wall of the arena (just below the seating) is in fact the back wall of the service corridor running around it.

21. A no doubt imaginative ancient depiction of the Colosseum. But note the entrance porch (topped by a chariot) on the left and the statues in the niches.

THE COLOSSEUM ABOVE GROUND

However confusing it can appear on the site itself, the basic design of the Colosseum is clear enough from the ground plan (

figure 1

): a series of concentric circles, leading in from the vast perimeter wall to the space of the arena in the centre. The surviving section of the perimeter wall on the north side (buttressed at each broken end in the nineteenth century) is arranged in four arcaded storeys, each of which corresponds to a floor level on the interior. On the first three storeys are open archways, with half columns in three different orders of architecture, Tuscan on the ground floor, Ionic on the first and Corinthian on the second (a sequence that was admired and often copied in Renaissance buildings). The top storey repeats the Corinthian order, but has small windows rather than open arches. The total height is 48 metres, and in its original extent it is estimated to have used some 100,000 cubic metres of travertine stone, quarried at nearby Tivoli.

At the very highest level of this outer wall are the sockets which were used to attach the awning (the ‘sails’ or ‘

vela

’) that served to keep the sun off the audience. (If you look up from the inside of the building when the sky is bright blue, these sockets are clearly visible.) It used to be thought – and it is still sometimes said – that the five stone bollards which survive on the ground to the east side of the Colosseum, about 18 metres away from the building, were also connected with the awning system: as if part of a series of giant tent pegs that would originally have

extended all round the building and have been used to anchor the ropes of the awnings to the ground. Part of a series they almost certainly were, but they would have been disastrously ill-suited to such a weighty task, as they have no foundations and are simply bedded into the soil. A much better guess is that they played some role in a controlling visitors and access to the building.

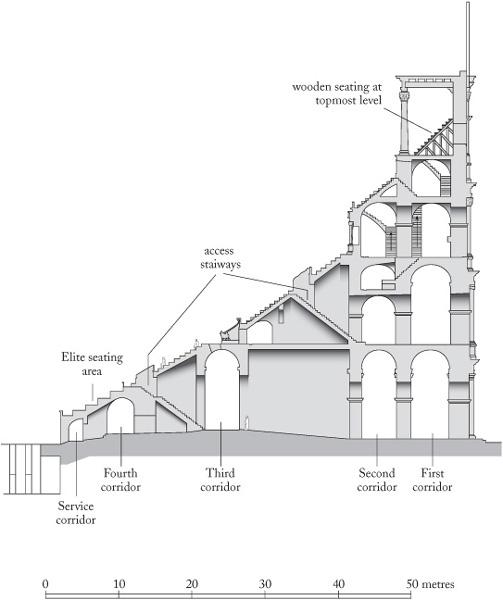

Working in from the exterior, we find a series of four circular corridors (usually known in studies of this building as ‘annular corridors’ from the Latin for ‘ring’, ‘

anulus

’). These give access to different parts of the monument and to the stairways leading up to higher levels as well as offering amenities such as water fountains and, we must assume, lavatories (though, unlike the fountains, no undisputed remains of lavatories have been discovered). These annular corridors supported the structures above, constructed in a mixture of travertine, other local stone and brick. As the cross-section shows (

figure 3

), the number of corridors decreases as you move further up the building.

There were eighty entranceways into the Colosseum from the outside. The four at the main axes were differentiated from the other seventy-six and it is generally assumed (on some – but frankly not very much – evidence) that these were used by the performers and the emperor and his party or by the officials presenting the show. The two on the long axis to east and west are usually taken to be the performers’ entrance and exit (the best argument for this is the adjacent stairs connecting them with the underground service areas of the Colosseum). Modern scholars (and ground plans) often slap technical-sounding Latin names on them: the ‘Porta Libitinensis’ or ‘Libitinaria’, after the goddess of death, Libitina, at the east, through which dead gladiators were removed; the ‘Porta Triumphalis’ at the west, through which the gladiators are supposed to have entered in procession at the start of the show (alternatively it is known as the ‘Porta Sanivivaria’ (‘Gate of Life’) through which the still living gladiators walked out of the arena at the end of their bout). In fact, there is almost no evidence for any of these names, still less that they were regularly applied at the Colosseum. The term ‘Porta Sanivivaria’, for example, is known only from the story of St Perpetua’s martyrdom in Carthage; ‘Porta Libitinensis’ comes from a single puzzling reference in a late biography of Commodus to the emperor’s helmet being twice taken out (it does not say from where) ‘through the Gate of Libitina’.