The Coming Plague (36 page)

Authors: Laurie Garrett

By the end of the 1970s the World Bank's solution was to urge poor nations to spend more on primary health care and disease prevention. This was done mostly through persuasion, such as the World Bank implying that “because of the emotional appeal of health issues, it may be politically attractive to redistribute welfare through government provision of health care.”

26

26

Reaching U.S. health care expenditure levels, even as a function of per capita annual spending, would, however, represent an extraordinary feat for most of the world's poor nations. According to the Carter administration, in 1976 in the United States there was a 1:600 ratio of physicians to the general population; virtually 100 percent of drinking water supplies were considered free from infectious disease; people consumed, on average, 133 percent of their minimum caloric need every day; 99 percent of adults were literate; 3.3 percent of the federal GNP was directed toward health care spending for a per capita spending rate of $259.

In contrast, Tanzania, for example, had one physician for every 18,490 citizens; safe drinking water was available to less than 40 percent of the

population; the average citizen consumed only 86 percent of the minimum daily caloric need; 34 percent of the adult population was illiterate; and the government spent 1.9 percent of its GNP on health care for a total of $3 annually per capita. Even if Tanzania doubled the percentage of its GNP devoted to health care, reaching U.S. percentage levels, it would still be spending less than $10 a year on each of its citizens. To reach U.S. annual expenditure rates of $259 per citizen, the Tanzanian government would have to rob nearly every other program in the government.

27

population; the average citizen consumed only 86 percent of the minimum daily caloric need; 34 percent of the adult population was illiterate; and the government spent 1.9 percent of its GNP on health care for a total of $3 annually per capita. Even if Tanzania doubled the percentage of its GNP devoted to health care, reaching U.S. percentage levels, it would still be spending less than $10 a year on each of its citizens. To reach U.S. annual expenditure rates of $259 per citizen, the Tanzanian government would have to rob nearly every other program in the government.

27

“It is stupid to rely on money as the major instrument of development when we know only too well that our country is poor,” Tanzania's one-party state proclaimed in its historic Arusha Declaration of 1967. “It is equally stupid, indeed it is even more stupid, for us to imagine that we shall rid ourselves of our poverty through foreign financial assistance rather than our own financial resources.”

Tanzania sought to create an infrastructure of modestly trained paramedics who worked out of tiny concrete or wattle clinics dispersed throughout the villages inhabited by most of the nation's ten million citizens. Between 1967 and 1976, the Tanzanian

Mtu ni Atya Chakula ni Uhai

village health campaigns increased the numbers of maternal/child health clinics by 610 percent, rural paramedics by 470 percent, and built 110 new medical facilities (for a total of 152 clinic structures nationwide by 1976). Life expectancy over that time increased seven years, reaching 47 (compared to 70 in Europe in 1976). Infant mortality also showed modest improvement, decreasing to 152:1,000 babies, compared to a 1967 level of 161:1,000 (with 1976 European infant mortality at 20:1,000).

28

Mtu ni Atya Chakula ni Uhai

village health campaigns increased the numbers of maternal/child health clinics by 610 percent, rural paramedics by 470 percent, and built 110 new medical facilities (for a total of 152 clinic structures nationwide by 1976). Life expectancy over that time increased seven years, reaching 47 (compared to 70 in Europe in 1976). Infant mortality also showed modest improvement, decreasing to 152:1,000 babies, compared to a 1967 level of 161:1,000 (with 1976 European infant mortality at 20:1,000).

28

Recognizing its acute need for physicians, the government built Muhimbili Medical School in Dar es Salaam and sent many bright young Tanzanians overseas for medical training, hoping to increase its national physician population by about 65 doctors a year. By 1975 the paramedicto-patient ratio was 1:454, but the physician-to-patient ratio had actually worsened, in part due to anti-Asian bigotry. Many of East Africa's besteducated residents were Indians, brought decades earlier as indentured labor by British colonialists in need of a literate bureaucratic class. In 1972 Uganda's dictator, Idi Amin (whose proclaimed hero was Adolf Hitler), ordered all Asians, numbering some 50,000 to 80,000, to leave the country immediately or face execution. No hue and cry of protest was raised by any other African government. Thousands of Indians, most of whom had spent all their lives in East Africa, fled not only Uganda but the continent as a whole.

29

29

Though such problems plagued all the poor nations on the planet, they were particularly acute in Africa because of its severe political and military instability. Nowhere else in the world were governments so recently freed from centuries of European colonialism. The Portuguese colonies of Guinea-Bissau, Angola, Mozambique, and Cape Verde only gained independence in the mid-1970s, after more than a decade of bloody civil war. In the southern part of the continent, warfare and instability would persist until the fates of Rhodesia, South Africa, Angola, and Southwest Africa were decided.

Â

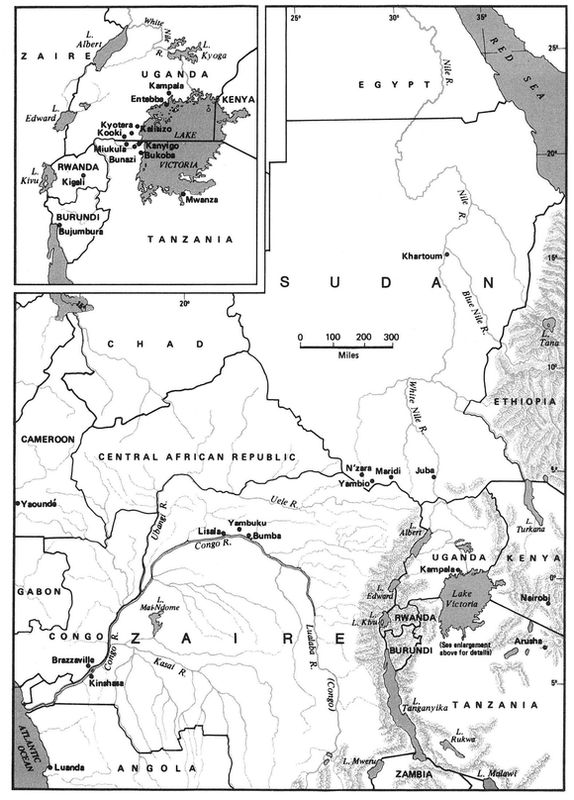

CENTRAL EAST AFRICA

To the north of those countries (which would eventually be named Zimbabwe, South Africa, Angola, and Namibia, respectively), lay a string of majority-ruled independent states sworn to boycott the still white-ruled southern states and support their various liberation movements. The Frontline States, as they were called, included Tanzania, Zambia, Mozambique, and, to a less militant degree, Lesotho and Botswana. Guerrilla troops representing the future governments of the region freely moved inside the Frontline States, and Lusaka was a sort of command post for SWAPO (South-West Africa People's Organization), ZAPU (Zimbabwe African People's Union), ZANU (Zimbabwe African National Union), and South Africa's ANC (African National Congress). Political exiles from the troubled south poured into the Frontline States, exacerbating their already acute economic difficulties. Furthermore, trade was severely impaired by the states' self-imposed boycott of South African ports and markets.

Elsewhere on the continent, civil instability was legion. Mobutu brutally smashed all dissent within Zaire. Self-appointed Emperor Bokassa ruled the Central African Republic with such brutality that he would eventually be overthrown by French paratroopers and tried for cannibalism and genocide. In an alleged anti-corruption cleanup campaign, junior elements of the military violently seized power in Ghana. Civil unrest due to religious and tribal disputes raged through Sudan, Morocco, Ethiopia, Mauritania, Angola, and Rwanda. Much of the warfare stemmed from the artificial national boundaries created by colonial powers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, dividing ancient tribal lands, extended families, and traditional power structures.

The superpowers, as well as the People's Republic of China, sought to manipulate these seemingly endless battles, hoping to align African governments with either the United States, the U.S.S.R., or China. As a result, obscene amounts of money were spent on the military and police forces of impoverished countries, squandered by dictators who made “gifts” to their nation's power elites in exchange for support, wired to the bank accounts of arms dealers worldwide.

Clearly, those funds were not spent on health care. Consider the examples of Tanzania and Uganda.

In 1979 Tanzania was celebrating its recent military victory over Uganda. Though the world's seventh pandemic

30

of cholera had struck Dar es Salaam and the lethal

Vibrio

bacteria coursed through the open sewer lines that crisscrossed the streets of the capital, little attention was paid to anything but the war. Pretty young girls proudly proclaimed victory across their rear ends, wearing

kangas

made from fabric emblazoned with the news. Young men wore their military uniforms as they strutted, heads held high, along Independence Avenue or past ANC headquarters on Nkrumah Street.

30

of cholera had struck Dar es Salaam and the lethal

Vibrio

bacteria coursed through the open sewer lines that crisscrossed the streets of the capital, little attention was paid to anything but the war. Pretty young girls proudly proclaimed victory across their rear ends, wearing

kangas

made from fabric emblazoned with the news. Young men wore their military uniforms as they strutted, heads held high, along Independence Avenue or past ANC headquarters on Nkrumah Street.

On his way to the Dar es Salaam airport in April 1979, Yusufu Lule anxiously cast his eyes about, looking for what he suspected was his last time at the city's street scene. After years of exile, he was about to take the reins of government in Uganda. Though he had agitated for Idi Amin's overthrow for years, the prospect of returning was frightening.

“It is chaos. We have a whole generation who don't know right from wrong. For years they have seen such brutalityârape, murder, theft, torture. I am going to a place where morality has no meaning,” Lule said with apparent dread.

Sixty-eight days later, Lule would be overthrown and Uganda would spin into a cycle of short-lived and vengeful governments.

It all began in 1971, when the Ugandan military overthrew the elected government of Milton Obote, putting a semi-literate, temperamentally violent man named Idi Amin in charge of the nation of some 18 million. Ten years earlier, Uganda had been considered one of the finest jewels in the British Empire's crown; a rich cornucopia of agricultural wealth with a well-established infrastructure of colonial and missionary schools, hospitals, roads, and trade. But Obote's government was also marked by corruption that fueled unrest and the 1971 military coup.

Amin destroyed the nation's prosperity and drove his country into a state of hellishness unlike anything it had previously experienced.

In 1975 Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere denounced Amin as “an oppressor, a black fascist, and a self-confessed admirer of fascism.” A few months later, Amin declared that, by ancient tribal rights, parts of Sudan, Kenya, and Tanzania belonged to Uganda. To drive home his point, Amin publicly executed a group of Kenyan students studying at universities in Entebbe and Kampala.

By 1977 Amin's government had committed so many atrocities both domestically and against its neighbors that the Western powers and Soviet Union had terminated diplomatic and trade relations. In response to British condemnation of Amin's human rights practices, said to include wholesale rape of women nationwide, as well as summary executions of tens of thousands of citizens of all ages, the dictator personally executed Anglican archbishop Luwum in front of hundreds of witnesses and television cameras.

“Thousands of innocent Ugandans have been floating in the river Nile in what the dictator and butcher Amin calls accidents,” charged Radio Tanzania on the day of Archbishop Luwum's execution. “If black African states condemn white minority rule [in South Africa and Rhodesia], they must also condemn atrocities committed in black-ruled states.”

By early 1978, according to the International Commission of Jurists in Geneva, Amin had summarily executed some 100,000 of his citizens, the trade agreement of the East African Community of Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania was formally dissolved, and both Kenya and Tanzania were placed on war-readiness status.

In October 1978, Amin's troops invaded the Kagera District in northern

Tanzania. A pastoral area lining the western shores of Lake Victoria, Kagera had no industry, only one small city (Bukoba), a scattering of hamlets, and no ability to defend itself against Amin's marauding forces. The Ugandan Air Force softened up the rolling verdant hillsides of Kagera with bombing raids. Troops followed, laying waste to the thatched huts and wattle structures of villages from one end of the district to another. For two months Amin's troops occupied a 700-square-mile area of Tanzania, killing hundreds of peasants, practicing deliberate rape of the women that was intended to humiliate their men, slaughtering most of the region's livestock, and driving some 40,000 peasants into exile.

Tanzania. A pastoral area lining the western shores of Lake Victoria, Kagera had no industry, only one small city (Bukoba), a scattering of hamlets, and no ability to defend itself against Amin's marauding forces. The Ugandan Air Force softened up the rolling verdant hillsides of Kagera with bombing raids. Troops followed, laying waste to the thatched huts and wattle structures of villages from one end of the district to another. For two months Amin's troops occupied a 700-square-mile area of Tanzania, killing hundreds of peasants, practicing deliberate rape of the women that was intended to humiliate their men, slaughtering most of the region's livestock, and driving some 40,000 peasants into exile.

Nyerere appealed for support from the Organization of African Unity (OAU) and the United Nations. None was forthcoming.

In December 1978, Tanzanian troops went to war with Uganda, fighting over the Kagera region for two months. Having beaten back Amin's troops, the Tanzanians pushed on toward the capital, Kampala.

On April 11, 1979, the Amin government was toppled. Idi Amin went into exile in Libya, and Tanzania put Lule in power.

The five-month war between Tanzania and Ugandaâwhich was puny by international standardsâdevastated the infrastructures of Uganda and northern Tanzania, and left the economies of both nations in a shambles. The combined impact of war and previous years of Amin's wantonness left Uganda in need of $2.3 billion in emergency reconstruction aid. It hurt Kenya's coffee trade, which had relied in part on Ugandan beans. And for the tiny, landlocked nations of Burundi and Rwanda it brought all trade to a standstill.

31

31

When Lule's staff took over the national bank, they discovered that Uganda was $250 million in debt to foreign interests, and less than $200,000 could be found in the nation's coffers. During his six-year reign, Amin simply printed more money whenever resources dwindled, causing annual inflation to run at 200 percent a year. Prior to the war gasoline sold in Kampala for $39 a gallon, housing rents increased 41 percent in a single year, while per capita income plummeted.

32

32

Well before the war erupted, most health professionals who could manage to do so had fled the country, and the severe economic difficulties created by the Amin government prompted wholesale looting of all undefended facilities.

Other books

We'll Never Tell (Secrets of Ravenswood) by Gallant, Jannine

Novel Experience (Sara Miles) by Quinn, Dacia

Talking to Dragons by Patricia C. Wrede

La forma del agua by Andrea Camilleri

Seduced by the Boss 3: For Her Pleasure by Jenn Roseton

The Arrangement by Hamblin, Hilary

The Avatar by Poul Anderson

Grave Endings by Rochelle Krich

Bewitched, Bothered, and Bitten by C.C. Wood

Pink Boots and a Machete by Mireya Mayor