The Complete Essays (91 page)

Read The Complete Essays Online

Authors: Michel de Montaigne

Tags: #Essays, #Philosophy, #Literary Collections, #History & Surveys, #General

[A] We might add that it is not for the criminal to decide how and when he will be whipped: it is for the judge, who can only take account of such chastisements as he himself has ordered and who cannot treat as punishment anything that is pleasing to the sufferer. Both for the sake of its own justice and of our punishment, God’s vengeance must presuppose our complete resistance to it.

[B] It was an absurd caprice on the part of Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, to cast his most precious jewel into the sea to atone for his continuous run of good fortune by interrupting its course; he thought to placate the turning Wheel of Fortune with a carefully arranged disaster. [C] Fortune, to mock such absurdity, caused the jewel to be returned into his hands through the belly of a fish.

[A] And then [C] what is the use of all those lacerations and loppings off of limbs practised by the Corybantes and Maenads, or, in our own day, by the Mahometans who slash their faces, their bellies and their limbs, to please their prophet, seeing that [A] the offence lies in the will not [C] in the breast, the eyes, the genitals, a well-rounded belly or in [A] the shoulders or the throat. [C]

‘Tantus est perturbatae mentis et sedibus suis pulsae furor, ut sic Dii placentur, quemadmodum ne homines quidem saeviunt’

[Such is their frenzy, arising from minds disturbed and forcibly unhinged, that it is thought the gods can be placated by surpassing even our human cruelty].

How we treat the natural fabric of our bodies concerns not only ourselves but the service of God and of other men. It is not right to harm it deliberately, just as it is wrong to kill ourselves on any pretext whatsoever. There is, it seems, both great treachery and great cowardice in whipping and mutilating the servile, senseless functions of our bodies in order to spare our souls the trouble of governing them reasonably:

‘Ubi iratos deos timent, qui sic propitios habere merentur? In regiae libidinis voluptatem castrati sunt quidam; sed nemo sibi, ne vir esset, jubente domino, manus intulit’

[What do they think the gods are angry about, when they believe they can propitiate them thus? Some have been castrated to serve the lust of kings, but no one has ever emasculated himself, even at the command of his master]. [A] In this way they filled their religion with many bad deeds,

saepius olim

Relligio peperit scelerosa atque impia facta

.

[Too often in the past, religion has given birth to impious and wicked actions.]

222

Nothing of ours can be compared or associated with the Nature of God, in any way whatsoever, without smudging and staining it with a degree of imperfection. How can infinite Beauty, Power and Goodness ever suffer any juxtaposition or comparison with a thing as abject as we are, without experiencing extreme harm and derogating from divine Greatness? [C]

‘Infirmum dei fortius est hominibus, et stultum Dei sapientius est hominibus’

[The weakness of God is stronger than men and the foolishness of God is wiser than men].

223

Stilpon the philosopher was asked whether the gods took pleasure in our homage and sacrifices: ‘You are most indiscreet,’ he replied; ‘if you want to talk about that, let us draw aside.’

224

[A] And yet we prescribe limits in the Infinite and besiege his mighty power with those reasons of ours (I call our ravings and our dreamings ‘reasons’, under the general dispensation of Philosophy who maintains that even the fool and the knave act madly ‘from reason’ – albeit from one special form of reason).

225

We wish to make God subordinate to our human understanding with its vain and feeble probabilities; yet it is he who has made both us and all we know. ‘Since nothing can be made from nothing: God could not construct the world without matter.’ What! Has God placed in our hands the keys to the ultimate principles of his power? Did he bind himself not to venture beyond the limits of human knowledge? Even if we admit, O Man, that you have managed to observe some traces of his acts here in this world, do you think that he has used up all his power by filling that work with every conceivable Form and Idea? You only see – if you see that much – the order and government of this little cave in which you dwell; beyond, his Godhead has an infinite jurisdiction. The tiny bit that we know is nothing compared with

ALL:

omnia cum coelo terraque marique

Nil sunt ad summam summai totius omnem

.

[The entire heavens, sea and land are nothing compared with the greatest

ALL

of all.]

226

The laws you cite are by-laws: you have no conception of the Law of the Universe. You are subject to limits: restrict yourself to them, not God. He is not one of your equals; he is not a fellow-citizen or a companion. He has revealed a little of himself to you, but not so as to sink down to your petty level or to make himself accountable for his power to you. The human body cannot fly up to the clouds – that applies to you! The Sun runs his ordered course and never stops still; the boundaries of sea and land can never be confounded; water is yielding and not solid; a material body cannot pass through a solid wall; a man cannot stay alive in a furnace; his body cannot be present in heaven, on earth and in a thousand places at once. It is for you that he made these laws; it is you who are restricted by them. God, if he pleases, can be free from all of them: he has made Christians witnesses to that fact. And in truth, since he is omnipotent, why should he restrict the measure of his power to definite limits? In whose interest ought he to give up being a Law unto himself?

That Reason of yours never attains more likelihood or better foundations than when it succeeds in persuading you that there are many worlds:

[B]

Terramque, et solem, lunam, mare, caetera quae sunt

Non esse unica, sed numero magis innumerali

.

[The earth, the sun, the moon and all that exists are not unique, but numerous beyond numbering.]

[A] That belief was held by the most famous minds of former ages (and still is by some today), on grounds which, to purely human reason, seem compelling, because nothing else within the fabric of the universe stands unique and alone:

[B]

cum in summa res nulla sit una,

Unica quae gignatur, et unica solaque crescat

.

[Since nothing born of Nature is unique, nor when it grows is anything unique or all alone.]

[A] There is some element of multiplicity within every species; it seems unlikely, therefore, that God made only this one universe and no other like it, or that all the matter available for this Form should have been exhausted on this one Particular:

[B]

Quare etiam atque etiam tales fateare necesse est

Esse alios alibi congressus materiai

,

Qualis hic est avido complexu quem tenet aether

.

[Such things must be said again and again: there are, elsewhere, other material aggregates than the one which the air enfolds in her keen embrace.]

[A] That is especially the case if the universe has a soul–something which its movements make credible, [C] so credible that Plato was sure of it; many Christians, too, either allow it or dare not disallow it, any more than the ancient opinion that the heavens, all heavenly bodies and other constituent parts of the universe are creatures composed of body and soul, subject to mortality, being composite, but immortal by the decree of their Maker.

227

[A] Now, if there are several worlds, as [C] Democritus, [A] Epicurus and almost the whole of philosophy have opined, how do we know whether the principles and laws which apply to this world apply equally to the others? Other worlds may present different features and be differently governed. [C] Epicurus thought of them as being both similar and dissimilar.

228

[A] Even within our own world we can see how mere distance produces infinite differences and variety. Neither

wheat nor wine was found in those New Lands discovered by our fathers, nor any of our animals: everything there is different. [C] And only think of those parts of the world which, in times gone by, had no knowledge of Bacchus’ grapes or Ceres’ corn.

[A] Should anyone care to believe Pliny [C] and Herodotus,

229

[A] there are species of men, in some places, which have very little resemblance to our own; [B] there are some ambiguous, mongrel forms, between the human and the beast; there are lands where men are born without heads, having eyes and mouths in their chests; there are androgynous creatures and creatures who walk on all fours, have only one eye in the middle of their forehead, or have a head more more like a dog’s than our own; some are fishes below the waist and live in water; some have wives who give birth at five and die at eight; other men have skin on their forehead and on the rest of their cranium so hard that iron spears cannot dent it but simply blunt themselves; there are men without beards, [C] peoples without the use or knowledge of fire and others who ejaculate black semen.

[B] What about those people who, by natural means, can change into wolves [C] and mares [B] and back again? And [A1] even if you were to accept as true [A] what Plutarch says (that somewhere in the Indies there are men without mouths who sustain themselves by inhaling certain smells) how many of our own descriptions today are certainly wrong!

230

If laughter were no longer the property of Man and if Man were no longer a political animal able to reason, our conception of what our inner disposition and causations are would be largely irrelevant…

231

To go further, we have imposed our own commandments on Nature and carved them in stone: yet how many things do we know which defy those fine rules of ours! And yet we try to bind God by them!

How many things are there which we call miraculous or contrary to Nature? [C] All men and nations do that according to the measure of their ignorance. [A] How many quintessences, how many occult properties have we discovered! For us, following Nature means following our

own intelligence as far as it is able to go and as far as we are able to see.

232

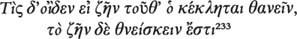

Everything else is a monster, outside the order of Nature! By that reasoning the cleverest and wisest men would find everything monstrous, since they are convinced that reason has no foundation to stand on, not even to determine [C] whether snow is white (Anaxagoras said it was black), or whether there are such things as knowledge and ignorance (Metrodorus of Chios denied that Man could ever know), [A] or even whether we are alive: Euripides hesitates, ‘Is

life

this life that we live now? Or is

life

really what we call death?’ That is:

[B] There is a degree of probability in that alternative: for why do we give the name

existence

to that instant which amounts to no more than a flash of lightning against the infinite course of eternal light, or to that tiny break which interrupts the condition which is naturally ours for all eternity, [C] since death fills everything before that moment and everything which comes afterwards as well as a large part of the moment itself?

[B] Some swear that nothing moves and that there is no such thing at all as motion – [C] as was believed by the followers of Melissus (since, as Plato proves, there is no place for spherical motion within strict Unity, nor even for movement from one place to another) – [B] or that there is, in Nature, no generation and no corruption. [C] Protagoras says that in Nature nothing exists but doubt: that everything is equally open to discussion, including the assertion that everything is equally open to discussion; Nausiphanes holds that among phenomena there is nothing which

is

rather than

is not

: that nothing is certain but uncertainty. For Parmenides, within the world of phenomena there is no such thing as genus: there is only Unity. For Zeno, there is not even Unity, only Nothing: for if Unity exists it must exist either within another or within itself; if it exists in another, that makes two; if it exists within itself, that still makes two – the container and the thing contained.

According to these tenets, Nature is but a shadow, false or vain.

234