The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (16 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

The first Samnite War (343â341

B

.

C

.

E

.) was fought for control around the city of Capua and ended in a treaty that left intact the Romans' alliance with Capua (just north of Naples) and the Samnites' holdings in central Italy.

The second Samnite War (327â303

B

.

C

.

E

.) was fought to a draw. The Romans suffered a great defeat (although how great has been questioned by historians) at Caudine Forks in 321

B

.

C

.

E

. The Samnites lured a Roman army into a narrow pass, captured it, and forced the Roman soldiers to surrender shamefully. Rome refused the terms of surrender and renewed the war.

Although the Samnites lost none of their territory, Rome gained in many ways. It learned how to make its fighting forces more flexible and maneuverable, and under the leadership of Appius Claudius Caecus, the Romans built the

Via Appia

(the famous Appian Way) from Rome to Capua. This road proved so important that they built roads to other parts of their emerging empire. The Roman “interstate highway system” became an important component in keeping the empire defensible, unified, and economically viable.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

From the city of Rome, you can still follow the ancient stones of the

Via Appia Antiqua

past Roman tomb monuments. The road was named for Appius Claudius Caecus, The Blind, the most influential Roman of this period. Appius instituted many important and popular social reforms (such as land redistribution) that kept Rome internally strong, built the first great Roman aqueduct (the

aqua Appia

), and proposed the road for troop movements to Capua that still bears his name.

The third Samnite War (298â290

B

.

C

.

E

.) was fought against Rome by the Samnites, Etruscans, and Gauls to try to stop Rome's continued expansion and control over Italy. By this time, Rome's strength was too great. The Samnites surrendered in 290

B

.

C

.

E

. and were assimilated into the status of Roman allies. When the Gauls and Etruscans settled a few years later, Rome had all but the very southern portion of Italy under its rule.

The Samnites were also fighting with the great Greek city of Tarentum. Tarentum depended on Greek mercenary forces, such as those under Alexander of Epirus in 334

B

.

C

.

E

. Alexander negotiated a treaty with the Romans, in which the Romans agreed neither to help the Samnites nor send ships into the bay of Tarentum. Nevertheless, Rome's defeat of the Samnites and the colonies that they established there involved them in the affairs of Magna Graecia (Greek colonies including Tarentum, Sybaris, Crotona, Heraclea, and Neapolis). Eventually, Tarentum attacked the Romans and called in King Pyrrhus of Epirus to help.

Pyrrhus had ambitions to be another

Alexander the Great

. He arrived in Italy in 280

B

.

C

.

E

. with 25,000 mercenary forces and 20 war elephants purchased from India. He won his battles, but at a high cost. The Samnites joined him, but the larger revolt

of Roman allies that he counted on never materialized. He attacked Sicily where he again bogged down after initial success against the Carthaginians, who protected their trading settlements and the Greek cities on the island.

Â

When in Rome

Alexander the Great

(356â323

B

.

C

.

E

.) was the greatest commander of antiquity. The son of Philip II of Macedon, who conquered Greece in 356

B

.

C

.

E

., Alexander conquered Egypt and Asia Minor all the way to the steps of the Himalayas before he died at the age of 33.

Pyrrhus finally returned to Epirus in 274

B

.

C

.

E

. where he again rescued defeat from the jaws of victory. After winning Macedon and most of Greece, he was killed when a woman threw a pot out of a second story window in the city of Argos and hit him on the head. That had to hurtâin more ways than one.

Tarentum, now on its own, surrendered to a Roman siege in 272

B

.

C

.

E

. With it, the Romans captured a great deal of booty, the fertile lands and trade routes of the south, control of all Italy, and Livius Andronicus. It was Andronicus, a Greek slave, who introduced the Romans to Greek drama and epic by translating the

Odyssey

into Latin. We'll talk more about him in Chapter 8, “Rome, Rome on the Range: Romans at Home,” but let's just note that this began the cultural and literary process by which, as the Roman poet Horace put it, “captive Greece captured its captor.”

Carthage was founded about 800

B

.

C

.

E

on the north African coast (in modern Tunisia) by Phoenician colonists. It grew into a great commercial and naval power (kind of like the Hudson's Bay Company) with settlements all over the western Mediterranean (including Spain and the islands of Sicily, Sardenia, and Corsica). From the birth of the Republic (509

B

.

C

.

E

.) through the invasion of Italy by Pyrrhus (280

B

.

C

.

E

.), Carthage and Rome were allies. Each had common interests against the Etruscans and the Greeks and separate spheres of influence. This situation ended when Rome had southern Italy firmly in its grasp. The two great states were now in a position where the Mediterranean was just not going to be big enough for both of them. This led to the Punic Wars.

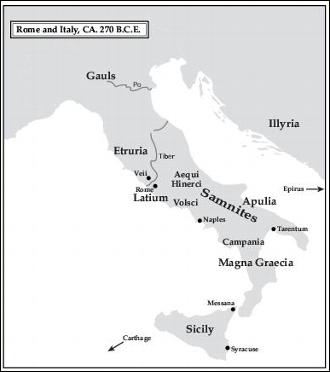

Rome and Italy, ca 270

B.C.E.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

The first Punic War was fought over Sicily. Mercenaries from Magna Graecia, the Mammertines, had been fighting there on behalf of Syracuse (the most powerful city in Sicily). There was a falling out over pay, and the Mammertines captured the Sicilian city of Messana (modern Messina). When Syracuse attacked the rebels, the Mammertines called on both Carthage and Rome for help.

Sicily was a rich and strategically situated island, and Rome was interested in having a piece of the pie. When both Rome and Carthage showed up to help the Mammertines, both Syracuse and the Mammertines soon became irrelevant. Rome wanted into Sicily, and Carthage wanted the Romans out. So, for the next 20 years, Rome and Carthage fought each other over Sicily. Eventually the Romans won and made Sicily the first Roman province in 241

B

.

C

.

E

. A few years later they forced the Carthaginians out of Sardinia and made that island a province as well. Carthage, like the proverbial elephant, never forgot the insult.

Elephant in the Living Room: Hannibal and the Second Punic War (218â202

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

The Romans were not sailors. At first they had a terrible time against the Carthaginians, but eventually found a way to make sea warfare more like land warfare. They outfitted ships with big landing ramps with a huge spike called a

corvus

(the “crow”) at the end. When they let down the gangwayâsmack!âthe spike stuck in the other ship. Then, instead of being able to run around like a berserk Gaul, the enemy ship had to sit there while the Romans ran across and attacked. This was one of the innovations that allowed them to defeat the Carthaginian fleet in 241

B

.

C

.

E

.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

When an empire takes a big hit, loose pieces start to shake and fall off. Carthaginian territories in Spain began to rebel after the loss of Sicily and Sardinia. The great Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barcawas was in charge of getting things back in order. Hamilcar carried a deep grudge against Rome. According to tradition, he brought his young son, Hannibal, with him and made him vow an undying oath of hatred against the Romans. Eventually, Hannibal inherited a loyal, well-trained, and well-armed army to carry out his vow.

The Romans and Carthaginians had an uneasy border in Spain along the Ebro River, and the flashpoint was the town of Saguntum. Hannibal conquered Saguntum, but there is some disagreement as to whether he meant this as a provocation. In any case, hotter heads prevailed, and hostilities began.

The Carthaginian (remember that Carthage had been a naval power) found himself in a strange situation. He had the better army but the Romans controlled the sea. Hannibal's only chance was to make Rome recall all its forces where its navy couldn't help it, and that place was Italy. But the only way to get to Italy without going along the coast was over the Alps.

The Romans, who considered the Alps their northern defense wall, sent one army to cut off Hannibal at the Rhone river and another to Sicily from where they could invade Africa and attack Carthage. But the first army arrived too late at the Rhone. Hannibal was already across and headed up the Alps. Rome, shocked and alarmed, began to scramble for a Plan B.

We don't know Hannibal's exact route, but the crossing is the stuff of legend. Attacked by Gauls and facing incredible challenges of logistics and terrain, Hannibal lost at least a third of his entire army. Still, he, 26,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry, and 20 of 60 elephants made their way down the Alps into Italy in 218

B

.

C

.

E

. There, Gauls who were already at war with Rome flocked to him, and he began to head south.

Even with the Gauls, Hannibal did not have the forces or support to attack Rome itself. His strategy was to try to break apart the Roman system from within. If he defeated Roman forces in Italy, allies in Italy might abandon Rome or revolt. If so, the reserves that gave Rome its stamina would be drained away. Moreover, because Rome had to call in troops from the borders of its empire to defend Italy, hostile forces in other places would begin to encroach and further weaken the overall system. Hannibal's plan was very nearly successful.

Hannibal won victories over the Romans in northern Italy at the Ticinus and Trebia rivers in 218

B

.

C

.

E

. The Romans tried to cut him off from central Italy, but he surprised them and took an unguarded route into Etruria. He then ambushed a Roman army of 36,000 under the leadership of Gaius Flaminius at Lake Trasemine in 217

B

.

C

.

E

. and destroyed it. Instead of marching on Rome, however, he headed into central and southern Italy.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Quintus Fabius's strategy of delay and harassment have come down to us in the expression “Fabian tactics.”

Rome elected the conservative Quintus Fabius to the office of dictator that year. Fabius adopted a very un-Roman strategy: He would not engage Hannibal head-to-head but rather keep his forces on high ground where Hannibal's cavalry had no advantage. This did not endear Fabius to Romans who were eager for a fight, and especially to those who had interests in the regions that Hannibal was pillaging. They nicknamed Fabius “Cunctator” (Delayer). When Fabius's term was over, they elected consuls (the chief magistrates and commanders) who would lead forces against Hannibal.

The ensuing battle at Cannae was a disasterâfor the Romans. Hannibal, in a brilliant display of tactics, pinned the full Roman army against a river and annihilated it. Over 70,000 Romans, including the consul and many important Romans, lost their lives. The Romans went to code blue, drafting boys above 16 and even slaves into the legions. The Samnites, cities in southern Italy, and Syracuse sided with Hannibal. Philip V of Macedon (northern Greece), who wanted the Romans to stay on their own side of the Adriatic, (see “The Illyrian Wars [229â228, 220â219

B

.

C

.

E

.]” later in this chapter), allied with Carthage. The Roman system was breaking apart at the seams.

But most alliances held, and the persistent Romans began to win back their interests in Spain, Sicily, and Illyria (the territory across the Adriatic from Italy). The Latins groaned under enormous burdens of taxation and military drafts, but eventually, after 15 years, the tide began to turn. Hannibal's one army couldn't protect his gains. He

summoned help from his brother's army in Spain, but the Romans, led by a young and brilliant general, Scipio, cut it off and defeated it at the Metaurus River in 207

B

.

C

.

E

. Scipio was then elected consul and sent with an army to north Africa, which forced Carthage to recall Hannibal. There, at the battle of Zama (modern Naraggara), Scipio defeated Hannibal in 202

B

.

C

.

E

. Rome became master of the western Mediterranean, and Scipio received the title “Africanus,” the “Conqueror of Africa.”

The Roman system of alliances, which had grown from judicious settlements with the Italians, had held against great odds. Rome was able to call on resources, built up through these alliances, and deploy them with persistence and skill. Fabius's intelligent tactics had given the Romans a chance to mobilize them yet again.

B

.

C

.

E

.)

After the battle of Zama, Hannibal himself brought the Romans' terms of surrender to Carthage and proposed acceptance. Terms were harsh: Carthage lost all its holdings outside Africa and had to recognize the independence of Numidia (which allied with Rome). Carthage paid an enormous yearly indemnity to Rome, and agreed not to wage war anywhere outside Africa and not within Africa without Roman permission.

Despite these terms, Carthage quickly recovered as a major economic power. Hannibal proved as good a civic administrator as a general. This didn't go down well at Rome, so Rome demanded Hannibal be surrendered as a war criminal. He fled to the east where the Romans continued to try to track him down as they conquered and expanded there. Hounded by the Romans until the end, Hannibal took poison to avoid capture in 182

B

.

C

.

E

.

Carthaginian economic strength continued to be a source of envy and worry to Rome. To complete their domination, the Romans manufactured a crisis with the help of its ally Numidia, who goaded Carthage into attacking it in 151

B

.

C

.

E

. so Rome could declare war. Carthage held out heroically but eventually surrendered in 146

B

.

C

.

E

. The city was destroyed, its inhabitants sold into slavery, and its lands made into the Roman province of Africa. That same year Rome also destroyed the Greek city of Corinth.