The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (41 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

Roamin' the Romans

The Mausoleum of Hadrian in Rome is known today as Castel San Angelo. This imposing structure was incorporated into Rome's and the Vatican's defenses in the Middle Ages and has served as a fortress, a prison, and a museum. The present name comes from a vision of an angel over the mausoleum, which signaled the end of a plague to Pope Gregory the Great in 590.

Hadrian's many buildings and projects, such as Castel San Angelo and his villa in Tivoli, remain as spectacular monuments today. You would think that these projects, coupled with discipline in the army, extension of the

alimenta

and citizen rights, reforms of military and provincial administration, and Hadrian's exhaustive attention to legal, civil, and administrative reforms and organization would make him a popular emperor. Not so. Hadrian was cranky, a strict disciplinarian who was difficult to be around. He was reportedly also a voracious sexual switch-hitter and seducer of married women. Only the soldiers adored their commander, who marched alongside of them and seemed to demand as much of himself as he did of them.

Hadrian lived out his final years in his magnificent villa at Tivoli, lonely and in growing pain from a medical ailment. This pain grew so bad that he sought suicide in attempts that ended in darkly comic frustration. Attendants kept sharp implements out of reach. He commanded his doctor to give him poison, but the panicked doctor took it himself. He commanded a servant to kill him and even marked out the spot to stab (“right here at the blue line”), but the servant bailed at the last minute and ran. Hadrian transferred power to his successor, Antoninus, and finally died at Baiae. Even in death, the traveling emperor traveled. With his mausoleum unfinished, Hadrian's body was first buried at Puteoli, exhumed to temporary digs in Rome, and then brought to his completed tomb.

Antoninus was from a prominent family and had limited military and administrative experience. He was 51 and probably chosen by Hadrian to hold things down until Hadrian's nephew, Marcus Aurelius, could become emperor. Antoninus adopted Marcus, who also married Antoninus's daughter. He was given the name “Pius” (Pious) for successfully opposing Hadrian's enemies in the senate who wanted to nullify his acts and desecrate his memory. Antoninus pointed out that his accession depended upon the authority and legitimacy of the man and the acts that they were condemning, and he quelled their opposition.

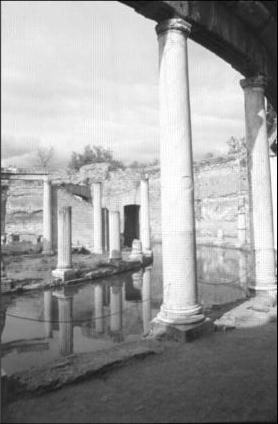

An artificial island in Hadrian's villa at Tivoli, where the emperor sought solitude from imperial pressures.

History seems to have taken a mostly “If you can't say anything bad, don't say anything at all” approach to Antoninus Pius. He was, by all accounts, fair, judicious, good-looking, well-spoken, even tempered, and a relatively unpretentious man who preferred administering the Empire from his country estates. Antoninus ruled for 23 years and never left Italy. Some of his most significant reforms were judicial, including the precedent of presumption of innocence and tie verdicts going in favor of the accused. Although there were no major wars during his reign, there was plenty of trouble on the borders to attend to. Antoninus did not put much effort into the military, however, and by the time of his death in 161, Rome's defenses and military were worn very thin.

Marcus Aurelius is one of the best-known emperors. People admire him for his nobility of character, which comes from the contrast between the emperor who relentlessly campaigned to hold the Empire together against enormous odds and the man who

wrote his simple and unpretentious Stoic reflections in the journal that has become known as the

Meditations.

Raised by his beloved adopted father and educated for duty, Marcus spent most of his years on the borders fighting the Parthians, Germanic invasions along the Danube (where he wrote the

Meditations

), a revolt in Syria, and the effects of a plague that ravaged the Empire.

Â

Lend Me Your Ears

“Tell yourself each morning, âToday I'm going to meet nosey, ungrateful, arrogant, untrustworthy, envious, and antisocial people. Bear in mind that they act this way because they don't realize what good and evil really are. I, however, realize that the nature of the good is beautiful and that the nature of evil is ugly, and that the nature of the person who does me wrong has a share of the same intelligence and divinity as I do. I can't really be hurt by any of them (since no one can pin ugliness on me) nor be angry at and hate my fellow human being. For we've been made for cooperation, like feet, hands, eyelids, and rows of teeth.' ”âMarcus Aurelius,

Thoughts to Himself

(in

Meditations

),

Book II;

after a translation by George Long

When Marcus was recognized as emperor, he insisted that his colleague, Lucius Varus, be given equal and commensurate power. Varus, according to imperial biographies, was a less dutiful leader than Marcus, and more interested in enjoying the power and luxury his position gave him. Nevertheless, he appears to have been a loyal colleague, and died while campaigning with Marcus in 169. The model of co-emperors was picked up later by Diocletian in an attempt to distribute the burdens of administering and defending the vast Empire. Marcus later faced down a strange uprising in 175 when his trusted governor of Syria, Cassius, was proclaimed emperor by his troops based on the rumor that Marcus was dead.

While Marcus was a pious philosopher, he wasn't necessarily a tolerant man. The Empire was under terrible strains, and Marcus viewed Roman traditions and religion as a part of the fabric that (barely) held it together. He therefore persecuted Christians

as members of a secretive and subversive cult. Overall, however, he worked tirelessly and fairly at hearing law cases, issuing imperial decisions and edicts, and defending the bordersâall of this apparently in the face of painful and deteriorating medical conditions for which he took the opiate theriac.

Marcus became very ill in Vindobona (Vienna), in 180. Advising his friends not to grieve for his death, for death was common to all, his last words were “Go to the rising sun; mine is setting.” So died the last of the “good” emperors, a man who, according to Dio, “both survived himself and preserved the Empire amid the most unusual and extraordinary troubles.” Unfortunately for Rome, however, these troubles survived Marcus, and passed on to his son and heir, Commodus.

The Least You Need to Know

Â

Roamin' the Romans

When in Rome, be sure to see the statue of Marcus astride a horse on the Capitoline, a stunning combination of serenity, grace, power, and movement. You should also visit his column at Piazza Colonna, which was modeled on Trajan's and shows scenes of Marcus's campaigns. Like Trajan's column, a statue of Marcus once stood at the top where St. Paul now surveys the prime minister's office.

- Nero's death put Rome into a brief time of anarchy.

- The Flavian emperors put Rome on a firm military and financial footing.

- The “good” emperors are known for adopting successors instead of passing power on to blood relations. Of course, it helped that only Marcus Aurelius had a son!

- The expansion of Rome under Trajan and Hadrian began to strain under Antoninus Pius, and to crumble under Marcus Aurelius.

Â

The (Mostly) Not-So-Good Emperors: Commodus to Aurelian

In This Chapter

- Pressures on the Empire after the “good” emperors

- The Severan dynasty

- Roman disintegration following the Severans

After Marcus Aurelius's death in 180, the Empire slipped into a period of decline and fragmentation with continual warfare on the borders. Rome became more of a symbolic capital; power concentrated in the provinces responsible for Rome's defense. This trend helped to transform regional warlords into emperors, and citizens under them eventually became more like serfs. But, if not for the restoration of the Empire under Diocletian in 285, we might have had the Dark Ages (ca 476â1000) a few centuries earlier.

People usually skim through this period. Understandably soâit's one of the most complicated and obscure periods in Roman history. Nevertheless, it contains some of the most interesting history of Rome and the early Christian church, which grew through persecutions both against and within itself in establishing doctrinal orthodoxy and institutional hierarchy. But by piecing together early Christian writers (such as Tertullian and Eusebius), fragments from Dio and other minor writers, and archeological evidence from the provinces, we're getting a better understanding of what went on. (For really detailed information you'll have to wait for

The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Barracks Emperors, 235â285.

)

In this chapter, we'll break up the period of the not-so-good emperors into three sections. The first goes from Commodus to the accession of Septemius Severus in 193. The second section covers the Severan dynasty, which ended with the murder of Severus Alexander in 235. The third is a black hole of assassinations, emperor-for-the-day military coups, invasions, and breakaway provinces that threatened to suck the Empire under until Diocletian reestablished order and stitched things back together in 285.