The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (45 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Â

Divide and (Re)Conquer: Diocletian to Constantine

In This Chapter

- The dominate of Diocletian

- The tetrarchy and its breakdown

- The rise of Constantine the Great

- The Christian emperor and empire

By the time of Diocletian, the Empire was completely mobilized for chaotic war and defense. Provincial armies fought invaders, fought themselves, or fought both while provincials suffered under the boot of repeated conquests and requests. Something new had to happen. The emperor needed to be more than a warlord, central authority and control had to be reestablished, and some binding imperial culture had to be developed. Most of all, stability of some kind had to settle in, or be imposed upon, the seething mass.

In this chapter, we'll follow how Diocletian set about imposing a new kind of structure, cohesion, and stability upon the Empire, and how this structure fell apart and came back together under Constantine the Great, who transformed the Roman Empire into a Christian enterprise.

Diocletian was an Illyrian soldier who rose through the ranks to become head bodyguard of the eastern emperor, Numerian. Numerian died mysteriously and the army proclaimed Diocletian emperor. The western emperor, Carinus, refused to recognize him, and the two armies fought. Carinus's army was on the point of winning when it

discovered that it had no leaderâa jealous tribune had knifed Carinus (who liked to sleep around with his officer's wives) during the battle. Both armies then accepted Diocletian as sole emperor.

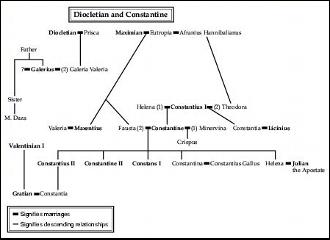

Diocletian and Constantine.

Diocletian faced huge problems in trying to complete the reunification and restoration of the Empire that Illyrian emperors such as Gallienus and Aurelian had started. Central authority had to be permanently reestablished around the emperor, who needed to become a unifying element to the whole in order to exert control. Imperial succession needed to be predictable to get the focus away from competing for succession and on to advancing the Empire. The huge provincial armies had to be redeployed to protect the Empire, not the provinces. The economy of the Empire needed stabilization and systemization to make state finances predictable.

Diocletian needed support from both east and west. He incorporated Carinus's supporters into his administration, building support and using their expertise. He himself, however, dispensed with any pretense of a principate and adopted the official title of “dominus,” or “lord and master.” Thus began the dominate (as opposed to the principate). He made the emperor more than a military and political autocrat by fashioning himself as “Jovius,” Jupiter's chosen one.

The emperor became the representative of the divine order of things, the Empire's right hand, heart,

and

soul. Public images showed his divine aspect by depicting him

surrounded by an

aura,

or halo. Diocletian reinforced the image by becoming a figure of mystery and awe. He rarely appeared in public and then only in wondrous regal and ceremonial garb. People were required to treat the emperor as divine, prostrate themselves before him, and kiss his robe. Prayers and sacrifices were offered to him.

Did he believe his press? Probably not, at least not in the way that Caligula and Commodus believed in their own divinity. Diocletian's actions speak of a man who had a method rather than a madness, and who was acting in line with a progression that stretched from Caesar through Aurelian.

Maximian

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

Early Christians had problems with Diocletian's attempts to unify the Empire around a divine emperor. They already had a reputation as subversive because they refused to participate in state sacrifices and prayers. After problems at imperial ceremonies, Diocletian first purged Christians from civil service and the military in 298. He went after churches and clergy in 303, and decreed in 304 that all Christians were to offer sacrifice to the emperor and the Roman gods on pain of death. Large-scale persecutions ensued, urged on by Diocletian's Caesar and heir, Galienus.

Diocletian recognized that the unified Empire was still too big for one man to govern effectively. He put a trusted colleague and general, Maximian, in charge of the west with the title of “Caesar” (Diocletian was “Augustus”).

Maximian was a Disneyland rags-to-riches story, the son of shopkeepers who rose through the military to become first a hero, then a co-emperor and a god. Raised to the title of “Augustus” in 286, Diocletian, in line with his program, made Maximian divine with the title “Hereculius.” The parallels between Jove (Diocletian) and Hercules (Maximian) were not lost on Maximian, who remained a loyal colleague of Diocletian.

Diocletian still needed to ensure a stable transition of his two-ruler system. He created a solution by having himself and Maximian (together called the Augusti) appoint heirs that would take over if either man died or retired. Each heir, or Caesar, would

assist his Augustus in ruling his respective hemispheres. Each Caesar also married into his Augustus's family to preserve the dynastic element.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

Maximian lost control of the north briefly when his naval commander, Carausius, revolted, took control of Britain, and declared himself emperor of the north alongside Maximian and Diocletian. Maximian was unable to bring Carausius under control, but Constantius succeeded in defeating Carausius and reconquering Britain. You can still find some of the fortifications from this period along the British coast, such as the Saxon shore fort at Burgh Castle, Suffolk.

Maximian appointed and adopted his praetorian commander, Constantius Chlorus. Constantius married Maximian's daughter, Theodora. Diocletian similarly adopted Galerius Maximianus as his Caesar, and Galerius married Diocletian's daughter, Valeria. This arrangement of four rulers is known as the

tetrarchy

(from Greek

tetra,

or four). Diocletian clearly had the dominant role, but imperial edicts and proclamations were made in all four tetrarchs' names. Each tetrarch had his own court and defended his territory from regional capitals. Maximian was based in Milan to protect the frontiers along the Rhine and Danube, while Constantius protected Gaul and the Rhine, and went on the reconquer Britain from his capital at Trier. Diocletian saw to the east from his base at Nicomedia (on the Sea of Marmara in modern Turkey), and Galerius saw to the lower Danube and northeast empire from Sirmium (on the Sauve in modern Yugoslavia).

Notice something here? Not one of the tetrarchs resided at Rome. Diocletian himself visited the city only once.

The tetrarchy worked remarkably well. Each tetrarch saw to their own areas and worked to pull the Empire together. The most notable achievements were probably those of Constantius. He put down Carausius

,

Gallic and Germanic rebellions, and then invaded Britain in 296. He reestablished Roman order from Hadrian's Wall south, cleared the area of pirates, and beautified Trier (Augusta Treverorum) as a thriving capital. Over their tenure, the tetrarchs worked together to defend the Empire efficiently, settle barbarian invaders, and stabilize Rome in a way that allowed the Empire to remain intact for another 200 years. But, the unifying element of the equation remained the personality, character, and drive of Diocletian; as soon as he was gone, the arrangement fell apart in typically Roman-esque fashion.

Diocletian did much more than reform the way that Rome was governed from the top. He applied innovations and complete overhauls to practically everything. He reorganized the provinces under the tetrarchs, grouping them into 12 dioceses under the administration of vicars. These terms, ironically (since Diocletian is known for persecuting Christians), remain active in the administrative language of the church.

Neither the provincial governors nor the vicars had military capabilities and were appointed by the tetrarchs. This arrangement kept provincial power fragmented and under control. In this reorganization, the Italians lost their tax-free status and became just another diocese.

The legions were broken into smaller units so they could be spread out along the borders more efficiently. Diocletian divided them into two classes: border guards (

limitanei

) and imperial troops (

comitatenses

). The latter were more highly trained and paid troops. They were held back from the border for rapid deployment to where they were needed once the

limitanei

were attacked.

Diocletian was a prodigious builder of roads, bridges, and palaces throughout the Empire. This activity and his sweeping administrative reforms took money and brought him face-to-face with a financial crisis of imperial proportions. Rome was mired in a manpower shortage, runaway inflation, currency problems, and layer upon layer of hodgepodge tax and tribute legislation.

Diocletian met these challenges head onâhe reformed the currency and established a regular tax collection system in the dioceses and provinces. Taxes on production were paid

in kind

(that is, if you made olive oil you paid in olive oil), and taxes on other assets or labor were assessed by a complicated system of tax units. Workers were organized into guilds (

collegia

) and required to remain where they were. Sons were required to take over their father's occupations. In this way, Diocletian made long-range planning possible and imperial revenues predictable.

Â

Lend Me Your Ears

“And so we encourage the diligent observance of all, so that the matter established out of public convenience might be safeguarded by willing compliance and religious obligation. Mostly, let it appear to have been established by a statue of this manner not just for particular cities, peoples and provinces, but for the whole world, to whose detriment a few people are known to have raged to the utmost extent, and whose greed neither an enormous span of time nor riches (for which they clearly have been eager), have been able to lessen or to satiate.”âDiocletian, from the Preface to his

Edict of Maximum Prices and Wages

But while the systemization and stabilization of the tax system was good for the Empire, it essentially reduced the common people to the position of serfs bound to the land or to their hereditary occupation. Rome had essentially become a totalitarian state. What's more, although Diocletian set the death penalty for law-breakers, his legislation broke economic laws that could not be repealed, even by a god. Prices continued to climb to the point where no one could afford to produce. Neither Diocletian's monetary reforms nor his famous

Edict of Maximum Prices and Wages

(published with a scathing attack on speculators) in 302 could stop this process.