The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire (9 page)

Read The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Roman Empire Online

Authors: Eric Nelson

Early Church Texts

Â

Roamin' the Romans

When in the Forum in Rome, walk through the Arch of Titus. Titus, the son of Vespasian, took over the siege of Jerusalem when his father left for Rome to become emperor in

C

.

E

. 69. Titus, accompanied by historian Josephus, stayed and conquered Jerusalem in 70. He then became emperor after Vespasian died. You can see Titus's triumphal parade carved into the arch, including a scene of the menorah from the temple in Jerusalem being carried as part of the spoils.

The story of the early Christian church is inexorably bound up with the Romans. Romans, such as the centurian whose daughter Jesus heals, Pontius Pilate, and the Roman emperor whom St. Paul appeals to in the book of Acts in the New Testament, play a pivotal role in church texts from the beginning. In addition, the Roman empire and the role that Rome played in the designs of the gods, God, or fate continued to be an issue in the struggle between pagan and Christian world views until about the sixth century

C

.

E

. We'll take a closer look at these texts and the transition of the Roman empire from pagan to Christian in Chapter 17, “Divide and (Re)Conquer: Diocletian to Constantine,” Chapter 20, “(Un)Protected Sects: Religions, Tolerance, and Persecutions,” and Chapter 21. Here, however, are two major writers to know:

- St. Augustine

(

C

.

E

. 354â430). The son of a pagan father and Christian mother, he was a highly educated teacher who converted to Christianity after a long intellectual and spiritual struggle. He eventually became the bishop of Hippo in Africa. Augustine's works, such as his

Confessions

and

City of God,

are among the most influential of early Christian literature and give us an illuminating perspective on this period in Roman history and culture. - Eusebius

(ca

C

.

E

. 265â340). Eusebius was the bishop of Caesarea in Palestine. Among his many works (written in Greek) is his “Ecclesiastical History,” which describes early Christianity's struggle within the Roman Empire until the conversion of the Emperor Constantine to Christianity in 314.

All right. The last chapter presented you with an overall framework for Roman history and literature. This chapter has given you an idea of how we know what we know about the Romans. You've read about some of the kinds of evidence that we

have, and where this evidence comes from. Next, let's give you some background. Rome was, in every way, the new kid on the block among the great civilizations that sprang up around the Mediterranean Basin. To understand and appreciate how Rome grew and developed, you need some perspective on what else was going on leading up to Rome's rise.

- The Romans left an enormous amount of archeological evidence about their culture.

- Excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum have provided an incredible treasure-trove of artifacts and information to give us a remarkably comprehensive look into Roman life in the first century

C

.

E

. - Roman textual evidence includes official documents, literature, and even graffiti.

- Texts about the Romans come from Roman, Greek, and Jewish authors.

Â

Club Mediterrania: Rome in the Context of Other Civilizations

In This Chapter

- Civilizations around the ancient Mediterranean

- Who's a barbarian?

- The many peoples of ancient Italy

- Rome at the crossroads of cultures

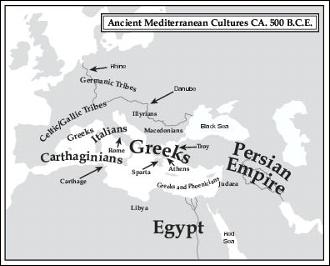

When Rome began to develop, it was a relative newcomer on the outskirts of a Mediterranean neighborhood with a history. To the east, there were the much older civilizations of Mesopotamia and Egypt. To the south, Greek colonies in southern Italy and Sicily were so numerous and so developed that the area got the name Magna Gracia (the Big Greece). Further south along north Africa, the Phoenician city of Carthage and its trading empire spread from Libya around the coast all the way to present-day southern France. There, more Greek colonies dotted the turbulent landscape of the west. Behind them, and along and over the Alps, Gauls, Goths, Celts, and other tribes ranged and roamed. And central Italy itselfâ

mamma mia!

âwas an antipasti buffet of Etruscans, Latins, Oscans, and other native peoples.

Let's take a look at what the different areas around the Mediterranean were like as Rome grew and developed, and what role they played as the Mediterranean became, for the Romans,

mare nostrum

âour pond.

Mediterranean cultures at about the time of the Roman revolution, ca 500

B.C.E.

The cultures of the Near East developed in Mesopotamia (between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers) during the early Bronze Age (back to roughly 5000

B

.

C

.

E

.). We don't have room to recap them all, but civilizations such as the Sumerians, Accadians, Babylonians, and Hittites go here. Let's start in about the eighth century

B

.

C

.

E

. (800â700

B

.

C

.

E

.) and work our way up to the time of Rome's revolution from the kings.

Persia

Â

Veto!

Converting centuries to years is a bit counterintuitive. It seems like the fifth century, for example, should include the years 500â599. But remember that, because we start from zero, the fifth century is 400â499. If you think of the century number name as being the

end

of the century, it's sometimes easier to keep straight. For example, the fifteenth century includes the hundred years leading

up to

1500 (1400â1499).

The Persians were an Aryan people who migrated into what is now Iran sometime before 800

B

.

C

.

E

. They established a great empire in the wake of the Assyrians and Babylonians beginning under Cyrus the Great (ca 550

B

.

C

.

E

.). Cyrus conquered Lydia (western Turkey) and the Greek city-states (Ionia) along the eastern Aegean. His successors conquered Egypt, pushed east into modern India, and gained a foothold in Europe. The Persians attempted to conquer Greece and made it as far as the Isthmus of Corinth, where the combined

forces of the Greeks turned them back and eventually forced them back across the Aegean.

The Persian Empire remained one of the major forces in the eastern Mediterranean until conquered by Alexander the Great about 330

B

.

C

.

E

. After his death, Persia was ruled by the Greek Seleucid dynasty and then by the Parthians (a native people from northern Persia). The Romans were able to conquer the Seleucids in western Asia Minor but not the Parthians.

The Phoenicians probably came from the Persian Gulf and settled up and down the eastern Mediterranean. Their primary cities were Sidon, Tyre, and Biblos. The Phoenicians were great traders and seafarers. They may be the origin of the mysterious Phaiacians, who finally brought Odysseus home to Ithaca in Homer's

Odyssey.

The Phoenicians founded the city of Carthage as a colony around 800

B

.

C

.

E

. Carthage grew into a trading empire of its own. The Phoenicians' most influential import was the alphabet.

Â

Great Caesar's Ghost!

More than just goods travel from one culture to another. Phoenician traders used a writing system in which pictorial symbols represented syllables of spoken language. The Greeks modified the symbols to represent individual phonetic sounds of their language. In Italy, the Etruscans modified the system and passed it on to the Romans. These writing systems came to be known by the first two symbols of the Phoenician script:

aleph

(ox) and

beth

(house)âthe alphabet.

The vast African continent borders the Mediterranean to the south, and different peoples had began to settle along north Africa in remote antiquity. The African continent west of Egypt was a mixture of indigenous tribes and settlements of Greeks and Phoenicians.

Â

Veto!

The famous Cleopatra (Cleopatra VII) was not a native Egyptian; she was a descendant of the kings who ruled over the Hellenistic (Greek) kingdoms formed from Alexander the Great's conquests. Her name is a very ancient Greek name, which means “her father's fame,” the same as Pato-cleo-s, the best friend of the Greek hero Achilles in Homer's

Iliad.

Â

Roamin' the Romans

If you're ever in Sicily, go as far west as you can and you'll eventually end up at Motya, the site of the last Carthaginian outpost on Sicily. Its extreme location is indicative both of the Carthaginians' role as sea traders and of the gradual westward exclusion of the Carthaginians from this strategic island.

Egypt is most often included with the cultures of Mesopotamia and the Near East, civilizations with whom it shares a rough chronology. Some scholars in the last century tended to treat Egypt as another early European outpost. More recently, books such as Martin Bernal's

Black Athena

have made the case for Egypt being recognized as an African civilization. Even though subsequent investigation has not sustained many of Bernal's sweeping claims, scholars have come again to see Egypt more like the Greeks and Romans did: as a distinct, and distinctly ancient, culture.

During the time of Rome's birth and rise to power, Egypt was viewed as the rich old granddaddy of civilizations. By the time Greeks and Romans arrived, Egyptian higher culture was already 2,000 years old, isolated, and ingrained. Conquests by the Persians and later by Alexander the Great never really had all that much impact on it. Even the Ptolemaic dynasty, which ruled over Egypt for 300 years (from 323

B

.

C

.

E

. until Cleopatra's suicide in 30

B

.

C

.

E

.), never really changed it. The Emperor Augustus took Egypt as his personal possession, and he and subsequent emperors used the riches of the province to stabilize the Roman empire's finances until they had drained most of it.

The Phoenicians established trading colonies and ports wherever they went, sort of like the Hudson's Bay Company did in North America. In about 800

B

.

C

.

E

., Phoenician settlers established the colony of Carthage in present-day Tunisia. The city's position just south of Sicily gave it a powerful position to exploit trade routes to the west. It grew quickly through trade and colonization throughout the western Mediterranean, and by the third century

B

.

C

.

E

., it was one of the Mediterranean's richest cities.

The Carthaginians were never in the mood for a land empire; they preferred to establish an empire of trade and of the sea, much as the Genovese and Venetians were to do in the late Middle Ages. They jealously guarded their trade routes and fought the Greeks and Etruscans for control of Sicily. A combined force of Etruscans and Greeks defeated them in 480

B

.

C

.

E

., and they were forced to the western part of the island.

The Carthaginians were at first allies of Rome. The two cities made treaties in 509 and 348

B

.

C

.

E

., and

Punic

fleets helped the Romans defeat Pyrrhus in 280

B

.

C

.

E

. As Roman power grew, however, the Mediterranean shrank and the two powers came into conflict. The Romans and Carthaginians fought three wars: the First Punic War (264â241

B

.

C

.

E

.), in which the Carthaginians lost Sicily; the Second Punic War (218â210

B

.

C

.

E

.), in which Hannibal invaded Italy and very nearly destroyed Rome; and the Third Punic War (149â156

B

.

C

.

E

.), which Rome provoked to finish off its weakened rival. Rome destroyed Carthage completely and made its territory into the province of Africa.

Libya and North Africa

Â

When in Rome

Punic

is derived from the Latin

Punici,

which the Romans called the Carthaginians. The word comes from their origin as Phoenicians. Classicists and historians therefore refer to the Roman wars with Carthage as the Punic, not Carthaginian, Wars.

All of north Africa was known pretty much as Libya. Greek and Phoenician settlements dominated the north coasts west of Egypt, and Phoenicians appear to have sailed down the Atlantic Coast as far as Sierra Leone. Behind the coastlands, the most prominent people with whom the Romans came into contact were the Numidians and the Moors.

Numidia was the region south and west of Carthage, populated by nomadic Berber tribes. The tribes had a loose coalition under a king. They were famous for their horsemanship; Hannibal used Numidian cavalry with great success against the Romans. Later, the Romans fought the Numidian king Jugurtha from 111â104

B

.

C

.

E

. Numidia was bordered in the south by the Sahara and to the west by what came to be called Mauretania, the land of the Moors.

Mauretania stretched from Numidia around the Straight of Gibraltar. The people were a mixture of African and Berber tribes with Phoenician settlements and were ruled by tribal chieftains. Some of the chieftains from this area played a part in the war with Jugurtha and in the later Roman Civil War; under Roman rule, it provided important cavalry units for Roman armies.