The Complete Yes Minister (19 page)

I should take this matter up with Humphrey tomorrow.

I shall also take up the matter of why my time is being wasted with footling meetings of this kind, when I want to spend much more time meeting junior staff here, getting to know their problems, and generally finding out how to run the Department more efficiently.

[

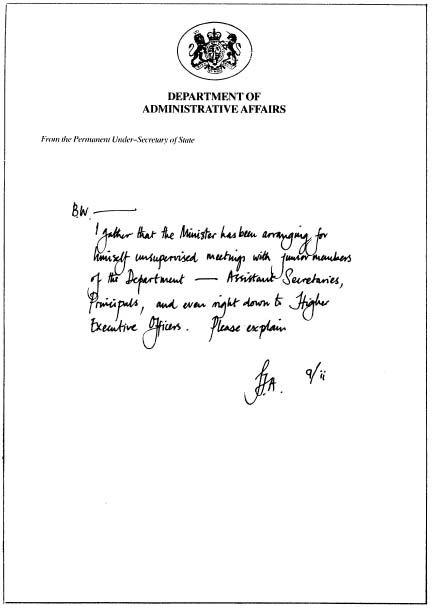

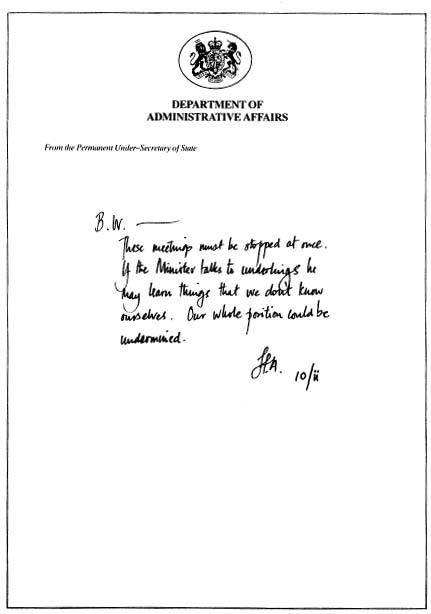

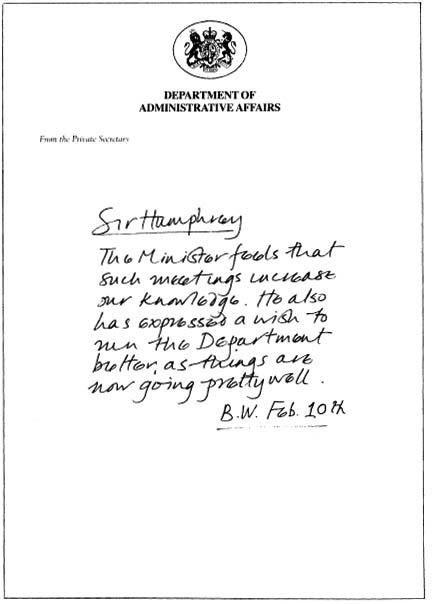

We discovered a remarkable exchange of memos between Sir Humphrey Appleby and Bernard Woolley, written during this week – Ed

.]

We discovered a remarkable exchange of memos between Sir Humphrey Appleby and Bernard Woolley, written during this week – Ed

.]

[

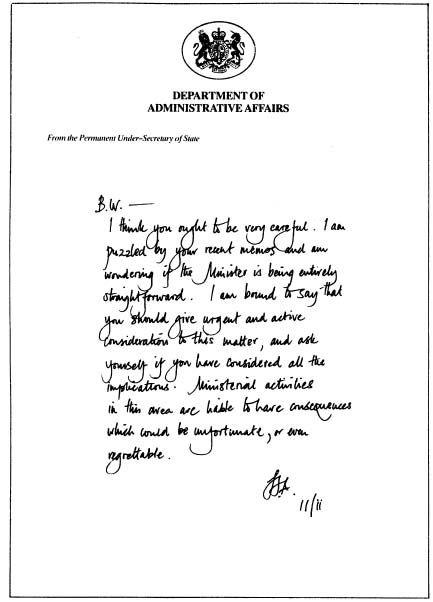

Translation: ‘Considered all the implications’ means ‘You are making a complete balls-up of your job.’ ‘Consequences which could be unfortunate, or even regrettable’ means ‘You are in imminent danger of being transferred to the War Graves Commission’ – Ed

.]

Translation: ‘Considered all the implications’ means ‘You are making a complete balls-up of your job.’ ‘Consequences which could be unfortunate, or even regrettable’ means ‘You are in imminent danger of being transferred to the War Graves Commission’ – Ed

.]

SIR BERNARD WOOLLEY RECALLS:

2

2

Being rather young and green at this time, I was still somewhat puzzled about how to put Sir Humphrey’s advice into practice, as the Minister made these diary appointments for himself and was getting thoroughly on top of his work.

I sought a meeting with Sir Humphrey, and began it by attempting to explain that I couldn’t prevent the Minister from doing what he wanted if he had the time.

Sir Humphrey was thunderously angry! He asked me why the Minister had free time. He told me to ensure that the Minister

never

had free time, and that it was my fault if he had. My job was to create activity. The Minister must make speeches, go on provincial visits, foreign junkets, meet deputations, work through mountains of red boxes, and be forced to deal with crises, emergencies and panics.

never

had free time, and that it was my fault if he had. My job was to create activity. The Minister must make speeches, go on provincial visits, foreign junkets, meet deputations, work through mountains of red boxes, and be forced to deal with crises, emergencies and panics.

If the Minister made spaces in his diary, I was to fill them up again. And I was to make sure that he spent his time where he was not under our feet and would do no damage – the House of Commons for instance.

However, I do recall that I managed to redeem myself a little when I was able to inform Sir Humphrey that the Minister was – even as we spoke – involved in a completely trivial meeting about preserving badgers in Warwickshire.

In fact, he was so pleased that I suggested that I should try to find some other threatened species with which to involve the Minister. Sir Humphrey replied that I need not look far – Private Secretaries who could not occupy their Ministers were a threatened species.

February 10th

This morning I raised the matter of the threatened furry animals, and the fact that I told the House that no loss of amenity was involved.

Sir Humphrey said that I’d told the House no such thing. The speech had contained the words: ‘No

significant

loss of amenity.’

significant

loss of amenity.’

I thought this was the same thing, but Sir Humphrey disabused me. ‘On the contrary, there’s all the difference in the world, Minister. Almost anything can be attacked as a loss of amenity and almost anything can be defended as not a significant loss of amenity. One must appreciate the significance of

significant

.’

significant

.’

I remarked that six books full of signatures could hardly be called insignificant. Humphrey suggested I look inside them. I did, and to my utter astonishment I saw that there were a handful of signatures in each book, about a hundred altogether at the most. A very cunning ploy – a press photo of a petition of six fat books is so much more impressive than a list of names on a sheet of Basildon Bond.

And indeed, the publicity about these badgers could really be rather damaging.

However, Humphrey had organised a press release which says that the relevant spinney is merely deregistered, not threatened; that badgers are very plentiful all over Warwickshire; that there is a connection between badgers and brucellosis; and which reiterates that there is no ‘significant loss of amenity’.

We called in the press officer, who agreed with Humphrey that it was unlikely to make the national press except a few lines perhaps on an inside page of

The Guardian

. The consensus at our meeting was that it is only the urban intellectual middle class who worry about the preservation of the countryside because they don’t have to live in it. They just read about it. Bernard says their protest is rooted more in Thoreau than in anger. I am beginning to get a little tired of his puns.

The Guardian

. The consensus at our meeting was that it is only the urban intellectual middle class who worry about the preservation of the countryside because they don’t have to live in it. They just read about it. Bernard says their protest is rooted more in Thoreau than in anger. I am beginning to get a little tired of his puns.

So we’d dealt satisfactorily with the problems of the animal kingdom. Now I went on to raise the important fundamental question: Why was I not told the full facts before I made the announcement to the House?

Humphrey’s reason was astonishing. ‘Minister,’ he said blandly, ‘there are those who have argued – and indeed very cogently – that on occasion there are some things it is better for the Minister not to know.’

I could hardly believe my ears. But there was more to come.

‘Minister,’ he continued unctuously, ‘your answers in the House and at the press conference were superb. You were convinced, and therefore convincing. Could you have spoken with the same authority if the ecological pressure group had been badgering you?’

Leaving aside this awful pun, which in any case I suspect might have been unintentional despite Humphrey’s pretensions to wit, I was profoundly shocked by this open assertion of his right to keep me, the people’s representative, in ignorance. Absolutely monstrous. I told him so.

He tried to tell me that it is in my best interests, a specious argument if ever I heard one. I told him that it was intolerable, and must not occur again.

And I intend to see that it doesn’t.

February 16th

For the past week Frank Weisel and I have been hard at work on a plan to reorganise the Department. One of the purposes was to have assorted officials at all levels reporting to me.

Today I attempted to explain the new system to Sir Humphrey, who effectively refused to listen.

Instead, he interrupted as I began, and told me that he had something to say to me that I might not like to hear. He said it as if this were something new!

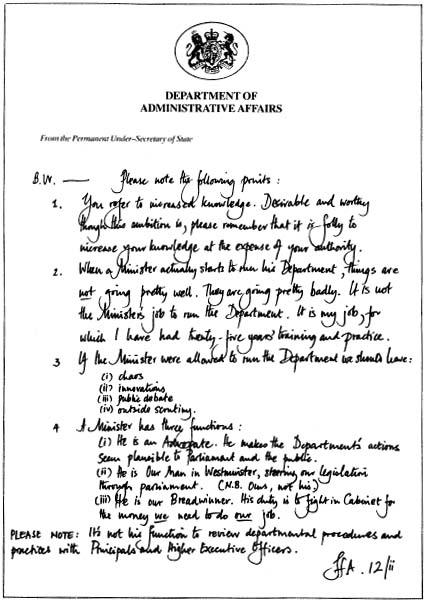

As it happens, I’d left my dictaphone running, and his remarks were recorded for posterity. What he actually said to me was: ‘Minister, the traditional allocation of executive responsibilities has always been so determined as to liberate the Ministerial incumbent from the administrative minutiae by devolving the managerial functions to those whose experience and qualifications have better formed them for the performance of such humble offices, thereby releasing their political overlords for the more onerous duties and profound deliberations that are the inevitable concomitant of their exalted position.’

I couldn’t imagine why he thought I wouldn’t want to hear that. Presumably he thought it would upset me – but how can you be upset by something you don’t understand a word of?

Yet again, I begged him to express himself in plain English. This request always surprises him, as he is always under the extraordinary impression that he has done so.

Nevertheless, he thought hard for a moment and then, plainly, opted for expressing himself in words of one syllable.

‘You are not here to run this Department,’ he said.

I was somewhat taken aback. I remarked that I think I am, and the public thinks so too.

‘With respect,’ he said, and I restrained myself from punching him in the mouth, ‘you are wrong and they are wrong.’

Other books

Firechild by Jack Williamson

Furnaces of Forge (The Land's Tale) by Skinner, Alan

Sweet Stuff by Kauffman, Donna

Shattered Trident by Larry Bond

You Don't Own Me: A Bad Boy Mafia Romance (The Russian Don Book 2) by Georgia Le Carre

A Searching Heart by Janette Oke

A Soldier in Love by A. Petrov

The Children's Crusade by Carla Jablonski

R.A. Salvatore's War of the Spider Queen: Dissolution, Insurrection, Condemnation by Richard Lee & Reid Byers, Richard Lee & Reid Byers, Richard Lee & Reid Byers

The Moses Stone by James Becker