The Complete Yes Minister (27 page)

‘One?’ I said.

‘Yes – the Deputy Chief Administrator fell over a piece of scaffolding and broke his leg.’

I began to recover myself. ‘My God,’ I said. ‘What if I’d been asked about this in the House?’ Bernard looked sheepish. ‘Why didn’t I know? Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I didn’t know either.’

‘Why didn’t you know? Who

did

know? How come this hasn’t got out?’

did

know? How come this hasn’t got out?’

Bernard explained that apparently one or two people at the DHSS knew. And they have told him that this is not unusual – in fact, there are several such hospitals dotted around the country.

It seems there is a standard method of preventing this kind of thing leaking out. ‘Apparently it has been contrived to keep it looking like a building-site, and so far no one has realised that the hospital is operational. You know, scaffolding and skips and things still there. The normal thing.’

I was speechless. ‘The normal thing?’ I gasped. [

Apparently, not quite speechless – Ed

.]

Apparently, not quite speechless – Ed

.]

‘I think . . .’ I was in my decisive mood again, ‘. . . I

think

I’d better go and see it for myself, before the Opposition get hold of this one.’

think

I’d better go and see it for myself, before the Opposition get hold of this one.’

‘Yes,’ said Bernard. ‘It’s surprising that the press haven’t found out by now, isn’t it?’

I informed Bernard that most of our journalists are so amateur that they would have grave difficulty in finding out that today is Thursday.

‘It’s actually Wednesday, Minister,’ he said.

I pointed to the door.

[

The following Friday Sir Humphrey Appleby met Sir Ian Whitchurch, Permanent Secretary of the Department of Health and Social Security, at the Reform Club in Pall Mall. They discussed St Edward’s Hospital. Fortunately, Sir Humphrey made a note about this conversation on one of his special pieces of margin-shaped memo paper. Sir Humphrey preferred to write in margins where possible, but, if not possible, simulated margins made him feel perfectly comfortable – Ed

.]

The following Friday Sir Humphrey Appleby met Sir Ian Whitchurch, Permanent Secretary of the Department of Health and Social Security, at the Reform Club in Pall Mall. They discussed St Edward’s Hospital. Fortunately, Sir Humphrey made a note about this conversation on one of his special pieces of margin-shaped memo paper. Sir Humphrey preferred to write in margins where possible, but, if not possible, simulated margins made him feel perfectly comfortable – Ed

.]

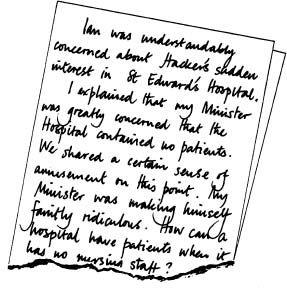

Ian was understandably concerned about Hacker’s sudden interest in St Edward’s Hospital.

[

We can infer from this note that Mr Bernard Woolley – as he then was – mentioned the matter of St Edward’s Hospital to Sir Humphrey, although when we challenged Sir Bernard – as he now is – on this point he had no recollection of doing so – Ed

.]

We can infer from this note that Mr Bernard Woolley – as he then was – mentioned the matter of St Edward’s Hospital to Sir Humphrey, although when we challenged Sir Bernard – as he now is – on this point he had no recollection of doing so – Ed

.]

I explained that my Minister was greatly concerned that the hospital contained no patients. We shared a certain sense of amusement on this point. My Minister was making himself faintly ridiculous. How can ahospital have patients when it has no nursing staff?

Ian quite rightly pointed out that they have great experience at the DHSS in getting hospitals going. The first step is to sort out the smooth-running of the place. Having patients around would be no help at all – they’d just get in the way. Ian therefore advised me to tell Hacker that this is the run-in period for St Edward’s.

However, anticipating further misplaced disquiet in political circles, I pressed Ian for an answer to the question: How long is the run-in period going to run? I was forced to refer to my Minister’s agreeing to a full independent enquiry.

Ian reiterated the sense of shock that he had felt on hearing of the independent enquiry. Indeed, I have no doubt that his shock is reflected throughout Whitehall.

Nevertheless, I was obliged to press him further. I asked for an indication that we are going to get some patients into St Edward’s

eventually

.

eventually

.

Sir Ian said that if possible, we would. He confirmed that it is his present intention to have some patients at the hospital, probably in a couple of years when the financial situation has eased up.

This seems perfectly reasonable to me. I do not see how he can open forty new wards at St Edward’s while making closures elsewhere. The Treasury wouldn’t wear it, and nor would the Cabinet.

But knowing my Minister, he may not see things in the same light. He may,

simply

because the hospital is treating no patients, attempt to shut down the whole place.

simply

because the hospital is treating no patients, attempt to shut down the whole place.

I mentioned this possibility to Ian, who said that such an idea was quite impossible. The unions would prevent it.

It seemed to me that the unions might not yet be active at St Edward’s, but Ian had an answer for that – he reminded me of Billy Fraser, the fire-brand agitator at Southwark Hospital. Dreadful man. He could be useful.

Ian’s going to move him on, I think. [

Appleby Papers 19/SPZ/116

]

Appleby Papers 19/SPZ/116

]

[

Perhaps we should point out that Hacker would not have been informed of the conversation described above, and Sir Humphrey’s memo was made purely as a private aide-mémoire – Ed

.]

Perhaps we should point out that Hacker would not have been informed of the conversation described above, and Sir Humphrey’s memo was made purely as a private aide-mémoire – Ed

.]

March 22nd

Today I had a showdown with Humphrey over Health Service Administration.

I had a lot of research done for me at Central House [

Hacker’s party headquarters – Ed

.] because I was unable to get clear statistics out of my own Department. Shocking!

Hacker’s party headquarters – Ed

.] because I was unable to get clear statistics out of my own Department. Shocking!

They continually change the basis of comparative figures from year to year, thus making it impossible to check what kind of bureaucratic growth is going on.

‘Humphrey,’ I began, fully armed with chapter and verse, ‘the whole National Health Service is an advanced case of galloping bureaucracy.’

Humphrey seemed unconcerned. ‘Certainly not,’ he replied. ‘Not galloping. A gentle canter at the most.’

I told him that instances of idiotic bureaucracy flood in daily.

‘From whom?’

‘MPs,’ I said. ‘And constituents, and doctors and nurses. The public.’

Humphrey wasn’t interested. ‘Troublemakers,’ he said.

I was astonished. ‘The public?’

‘They are some of the worst,’ he remarked.

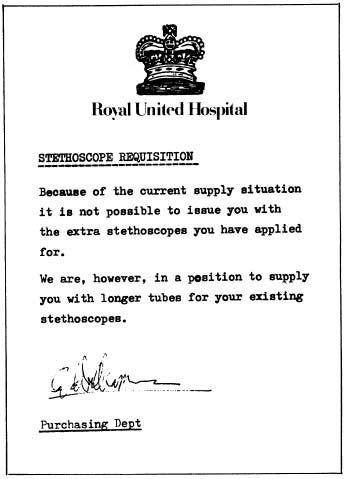

I decided to show him the results of some of my researches. First I showed him a memo about stethoscopes. [

As luck would have it, Hacker kept copies of all the memos to which he refers in his diary. These give us a fascinating insight into the running of the National Health Service in the 1980s – Ed

.]

As luck would have it, Hacker kept copies of all the memos to which he refers in his diary. These give us a fascinating insight into the running of the National Health Service in the 1980s – Ed

.]

Sir Humphrey saw nothing strange in this and commented that if a supply of longer tubes was available it was right and proper to make such an offer.

Bernard then went so far as to suggest that it could save a lot of wear and tear on the doctors – with sufficiently long tubes for their stethoscopes, he suggested, they could stand in one place and listen to all the chests on the ward.

I hope and pray that he was being facetious.

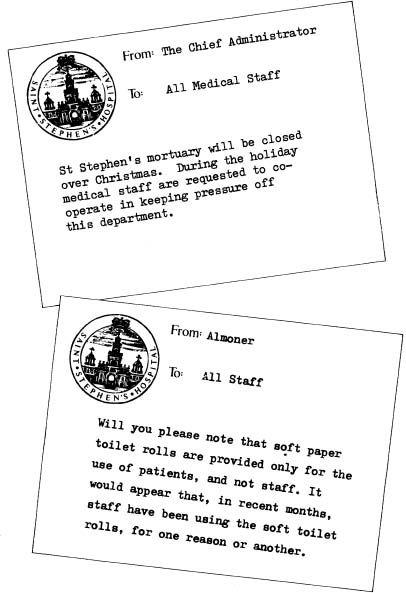

Then I showed Humphrey the memos from St Stephen’s about toilet rolls and the mortuary.

Sir Humphrey brushed these memos aside. He argued that the Health Service is as efficient and economical as the government allows it to be.

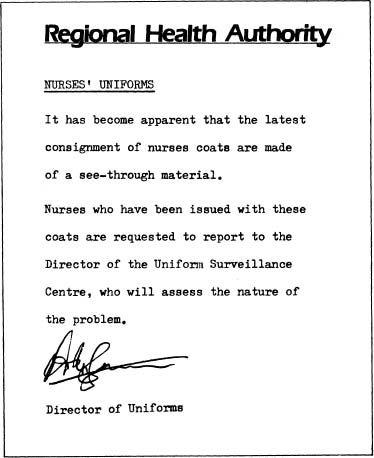

So I showed him a quite remarkable document from the Director of Uniforms in a Regional Health Authority:

Humphrey had the grace to admit he was amazed by this piece of nonsense. ‘Nice work if you can get it,’ he said with a smile.

I saved my trump card till last. And even Humphrey was concerned about the Christmas dinner memo:

Humphrey did at least admit that something might be slightly wrong if we are paying people throughout the NHS to toil away at producing all this meaningless drivel. And I learned this morning that in ten years the number of Health Service administrators has gone up by 40,000 and the number of hospital beds has gone down by 60,000. These figures speak for themselves.

Furthermore the annual cost of the Health Service has gone up by one and a half billion pounds. In real terms!

But Sir Humphrey seemed pleased when I gave him these figures. ‘Ah,’ he said smugly, ‘if only British industry could match this growth record.’

I was staggered! ‘Growth?’ I said. ‘Growth?’ I repeated. Were my ears deceiving me? ‘Growth?’ I cried. He nodded. ‘Are you suggesting that treating fewer and fewer patients so that we can employ more and more administrators is a proper use of the funds voted by Parliament and supplied by the taxpayer?’

‘Certainly.’ He nodded again.

I tried to explain to him that the money is only voted to make sick people better. To my intense surprise, he flatly disagreed with this proposition.

‘On the contrary, Minister, it makes

everyone

better – better for having shown the extent of their care and compassion. When money is allocated to Health and Social Services, Parliament and the country feel cleansed. Absolved. Purified. It is a sacrifice.’

everyone

better – better for having shown the extent of their care and compassion. When money is allocated to Health and Social Services, Parliament and the country feel cleansed. Absolved. Purified. It is a sacrifice.’

This, of course, was pure sophism. ‘The money should be spent on patient care, surely?’

Sir Humphrey clearly regarded my comment as irrelevant. He pursued his idiotic analogy. ‘When a sacrifice has been made, nobody asks the Priest what happened to the ritual offering after the ceremony.’

Humphrey is wrong, wrong, wrong, wrong! In my view the country

does

care if the money is misspent, and I’m there as the country’s representative, to see that it isn’t.

does

care if the money is misspent, and I’m there as the country’s representative, to see that it isn’t.

‘With respect,

3

Minister,’ began Humphrey, one of his favourite insults in his varied repertoire, ‘people merely care that the money is not

seen

to be misspent.’

3

Minister,’ began Humphrey, one of his favourite insults in his varied repertoire, ‘people merely care that the money is not

seen

to be misspent.’

Other books

Dead Politician Society by Robin Spano

Wicked Intentions by Linda Verji

Scandal in Seattle by Nicole Williams

Rock Hard: A Stepbrother Romance (Extreme Sports Alphas) by Hamel, B. B.

How to Romance a Rake by Manda Collins

Demons of Lust by Silvana S Moss

Miracle Jones by Nancy Bush

The Devil of Jedburgh by Claire Robyns

Tattletale Mystery by Gertrude Chandler Warner

Fair Play by Madison, Dakota