The Complete Yes Minister (43 page)

I suppose I was hoping for high praise. ‘Superbly’ would have been a nice answer. As it was, Bernard nodded and said, ‘Yes, you’ve done all right.’

It seems that no one is prepared to commit themselves further than that on the subject of my performance. It really is rather discouraging. And it’s not my fault I’ve not been a glittering success, Humphrey has blocked me on so many issues, he’s never really been on my side. ‘Look, let’s be honest,’ I said to Bernard. ‘

All right

isn’t good enough, is it?’

All right

isn’t good enough, is it?’

‘Well . . . it’s all right,’ he replied carefully.

So I asked him if he’d heard any rumours on the grapevine. About me.

He replied, ‘Nothing, really.’ And then he added: ‘Only that the British Commissioner in Europe sent a telegram to the FCO [

Foreign and Commonwealth Office – Ed

.] and to the Cabinet Committee on Europe, that the idea for you to be a Commissioner came from Brussels but that it is – at the end of the day – a Prime Ministerial appointment. The Prime Minister has in fact discussed it extensively with the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and the Secretary to the Cabinet, and cleared the way for you to be sounded out on the subject. As it is believed at Number Ten that you might well accept such an honour, a colleague of yours has been sounded out about becoming our Minister here at the DAA.’ He paused, then added apologetically, ‘I’m afraid that’s all I know.’

Foreign and Commonwealth Office – Ed

.] and to the Cabinet Committee on Europe, that the idea for you to be a Commissioner came from Brussels but that it is – at the end of the day – a Prime Ministerial appointment. The Prime Minister has in fact discussed it extensively with the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs and the Secretary to the Cabinet, and cleared the way for you to be sounded out on the subject. As it is believed at Number Ten that you might well accept such an honour, a colleague of yours has been sounded out about becoming our Minister here at the DAA.’ He paused, then added apologetically, ‘I’m afraid that’s all I know.’

‘No more than that?’ I asked with heavy irony.

I then asked which colleague had been sounded out to replace me at the DAA. Bernard didn’t know.

But I was really getting nowhere with my basic problem. Which is, if I don’t go to Europe will I be pushed up, or down – or out!

July 15th

Rumours suggest that the reshuffle is imminent. The papers are full of it. Still no mention of me, which means the lobby correspondents have been told nothing one way or the other.

It’s all very nerve-racking. I’m quite unable to think about any of my ministerial duties. I’m becoming obsessed with my future – or lack of it. And I must decide soon whether to accept or decline Europe.

I had a meeting with Sir Humphrey today. It was supposed to be on the subject of the Word Processing Conference in Brussels.

I opened it up by telling Humphrey that I’d changed my mind. ‘I’ve decided to go to Brussels,’ I said. I meant go and have a look, as I’d arranged with Annie. But Humphrey misunderstood me.

‘You’re not resigning from the Department of Administrative Affairs?’ he asked. He seemed shocked. I was rather pleased. Perhaps he has a higher opinion of me than I realised.

I put him out of his misery. ‘Certainly not. I’m talking about this Word Processing Conference.’

He visibly relaxed. Then I added, ‘But I would like to see Brussels for myself.’

‘Why?’ he asked.

‘Why not?’ I asked him.

‘Why not indeed?’ he asked me. ‘But why?’

I told him I was curious. He agreed.

Then I told him, preparing the ground for my possible permanent departure across the Channel, that I felt on reflection that I’d been a bit hasty in my criticisms of Brussels and that I’d found Humphrey’s defence of it thoroughly convincing.

This didn’t please him as much as I’d expected. He told me that he had been reflecting on

my

views, that he had found much truth and wisdom in my criticism of Brussels. (Was this Humphrey speaking? I had to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming.)

my

views, that he had found much truth and wisdom in my criticism of Brussels. (Was this Humphrey speaking? I had to pinch myself to make sure I wasn’t dreaming.)

‘You implied it was corrupt, and indeed you have opened my eyes,’ he said.

‘No, no, no,’ I said hastily.

‘Yes, yes,’ he replied firmly.

I couldn’t allow Humphrey to think that I’d said it was corrupt. I

had

said it, actually, but now I’m not so sure. [

We are not sure whether Hacker was not sure that he wanted to be quoted or not sure that Brussels was corrupt – Ed

.] I told Humphrey that he had persuaded

me

. I can now see, quite clearly, that Brussels is full of dedicated men carrying a heavy burden of travel and entertainment – they need all that luxury and the odd drinkie.

had

said it, actually, but now I’m not so sure. [

We are not sure whether Hacker was not sure that he wanted to be quoted or not sure that Brussels was corrupt – Ed

.] I told Humphrey that he had persuaded

me

. I can now see, quite clearly, that Brussels is full of dedicated men carrying a heavy burden of travel and entertainment – they need all that luxury and the odd drinkie.

‘Champagne and caviar?’ enquired Sir Humphrey. ‘Private planes, air-conditioned Mercedes?’

I reminded Humphrey that these little luxuries oil the diplomatic wheels.

‘Snouts in the trough,’ remarked Humphrey, to no one in particular.

I reproved him. ‘That is not an attractive phrase,’ I said coldly.

‘I’m so sorry’, he said. ‘I can’t think where I picked it up.’

I drew the discussion to a close by stating that we would all go to Brussels next week to attend this conference, as he had originally requested.

As he got up to leave, Humphrey asked me if my change of heart about Brussels was entirely the result of his arguments.

Naturally, I told him yes.

He didn’t believe me. ‘It wouldn’t be anything to do with rumours of your being offered a post in Brussels?’

I couldn’t let him know that he was right. ‘The thought is not worthy of you, Humphrey,’ I said. And, thinking of Annie and trying not to laugh, I added solemnly: ‘There is such a thing as integrity.’

Humphrey looked confused.

[

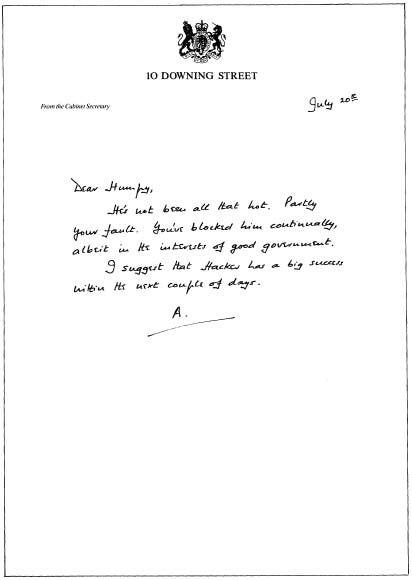

Later that day Sir Humphrey had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, Secretary to the Cabinet, at their club. He made the following note in his private diary – Ed

.]

Later that day Sir Humphrey had lunch with Sir Arnold Robinson, Secretary to the Cabinet, at their club. He made the following note in his private diary – Ed

.]

I told Arnold that I was most concerned about letting Corbett loose on the DAA. I would regard it as a disaster of the utmost magnitude.

Arnold said that he was unable to stop the move. The Prime Minister appoints the Cabinet. I refused to accept this explanation – we all know perfectly well that the Cabinet Secretary arranges reshuffles. I said as much.

Arnold acknowledged this fact but insisted that, if the PM is really set on making a particular appointment, the Cabinet Secretary must reluctantly acquiesce.

I remain convinced that Arnold keeps a hand on the tiller.

[

The matter rested there until Sir Humphrey Appleby received a memo from Sir Arnold Robinson, see below – Ed

.]

The matter rested there until Sir Humphrey Appleby received a memo from Sir Arnold Robinson, see below – Ed

.]

A memo from Sir Arnold Robinson to Sir Humphrey Appleby:

A reply from Sir Humphrey Appleby:

A reply from Sir Arnold:

A reply from Sir Humphrey:

A reply from Sir Arnold:

July 22nd

I was still paralysed with indecision as today began.

At my morning meeting with Humphrey I asked if he had any news. He denied it. I know he had lunch with the Cabinet Secretary one day last week – is it conceivable that Arnold Robinson told him nothing?

‘You must know something?’ I said firmly.

Slight pause.

‘All I know, Minister, is that the reshuffle will definitely be announced on Monday. Have

you

any news?’

you

any news?’

I couldn’t think what he meant.

‘Of Brussels,’ he added. ‘Are you accepting the Commissionership?’

I tried to explain my ambivalence. ‘Speaking with my Parliamentary hat on, I think it would be a bad idea. On the other hand, with my Cabinet hat on, I can see that it might be quite a good idea. But there again, with my European hat on, I can see that there are arguments on both sides.’

I couldn’t believe the rubbish I could hear myself talking. Humphrey and Bernard might well have wondered which hat I was talking through at the moment.

They simply gazed at me, silent and baffled.

Humphrey then sought elucidation.

‘Minister, does that mean you have decided you want to go to Brussels?’

‘Well . . .’ I replied, ‘yes and no.’

I found that I was enjoying myself for the first time for days.

Humphrey tried to help me clarify my mind.

He asked me to list the pros and cons.

This threw me into instant confusion again. I told him I didn’t really know what I think, thought, because – and I don’t know if I’d mentioned this to Humphrey before, I think I

might

have – it all rather depends on whether or not I’ve done all right. So I asked Humphrey how he thought I’d done.

might

have – it all rather depends on whether or not I’ve done all right. So I asked Humphrey how he thought I’d done.

Humphrey said he thought I’d done all right.

So I was no further on. I’m going round and round in circles. If I’ve done all right, I mean

really

all right, then I’ll stay because I’ll be all right. But if I’ve only done all right, I mean only

just

all right, then I think to stay here wouldn’t be right – it would be wrong, right?

really

all right, then I’ll stay because I’ll be all right. But if I’ve only done all right, I mean only

just

all right, then I think to stay here wouldn’t be right – it would be wrong, right?

Humphrey then appeared to make a positive suggestion. ‘Minister,’ he volunteered, ‘I think that, to be on the safe side, you need a big personal success.’

Great, I thought! Yes indeed.

‘A triumph, in fact,’ said Humphrey.

‘Like what?’ I asked.

‘I mean,’ said Humphrey, ‘some great personal publicity for a great personal and political achievement.’

I was getting rather excited. I waited expectantly. But suddenly Humphrey fell silent.

‘Well . . .’ I repeated, ‘what have you in mind?’

‘Nothing,’ he said. ‘I’m trying to think of something.’

Other books

Operator - 01 by David Vinjamuri

Sugar Coated Sins by Jessica Beck

Wizard's Funeral by Kim Hunter

Sins of the Fathers by Patricia Hall

Phobia KDP by Shives, C.A.

This Time by Ingrid Monique

The Babylon Rite by Tom Knox

Beyond the Ivory Tower by Jill Blake

[Southern Arcana 2.0] Crossroads by Moira Rogers

Leaving the World by Douglas Kennedy