The Complete Yes Minister (47 page)

[

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

Hacker’s diary continues – Ed

.]

September 20th

For some reason they didn’t run the story of my visit to the City Farm in the

Standard

last week.

Standard

last week.

But today I got a double-page spread. Wonderful. One photo of me with a duck, another with a small multiracial girl. Great publicity for me, and the Department.

I was busy discussing the possibilities of visiting other City Farms – in Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow, Newcastle. Preferably in the Special Development Areas. [

The new euphemism for marginal constituencies – Ed

.]

The new euphemism for marginal constituencies – Ed

.]

This happy conversation was rudely interrupted by Bernard announcing that the wretched Mrs Phillips was outside in the Private Office, demanding to see me.

I couldn’t see why. Then Bernard told me that it was announced this morning that the City Farm is being closed. This was a bombshell.

‘The lease runs out at the end of the year and it’s being turned into a car park,’ Bernard told me. ‘For Inland Revenue Inspectors.’

Bill and I both knew what the headlines would be. CHILDREN AND ANIMALS EVICTED BY TAXMEN. HACKER RENEGES ON TV PLEDGE. That sort of thing.

I told Bernard that it simply couldn’t be allowed to happen. ‘Which idiot authorised it?’ I asked.

He stared unhappily at his shoes. ‘I’m afraid, er, you did, Minister.’

It seems that the administrative order that I signed a couple of days ago, which Humphrey said was so urgent, gives government departments the power to take over local authority land. It’s known as Section 7, subsection 3 in Whitehall.

I sent for Humphrey. I told Bernard to get him

at once

, pointing out that this is about the worst disaster of the century.

at once

, pointing out that this is about the worst disaster of the century.

There

were

two World Wars, Minister,’ said Bernard as he picked up the phone. I simply told him to shut up, I was in no mood for smartarse insubordination.

were

two World Wars, Minister,’ said Bernard as he picked up the phone. I simply told him to shut up, I was in no mood for smartarse insubordination.

‘Fighting on the beaches is one thing,’ I snarled. ‘Evicting cuddly animals and small children to make room for tax inspectors’ cars is in a different league of awfulness.’

Humphrey arrived and started to congratulate me on my television appearance. What kind of a fool does he think I am? I brushed this nonsense aside and demanded an explanation.

‘Ah yes,’ he said smoothly. ‘The Treasury, acting under Section 7, subsection 3 of the Environmental . . .’

‘It’s got to be stopped,’ I interrupted brusquely.

He shook his head, and sighed. ‘Unfortunately, Minister, it is a Treasury decision and not within our jurisdiction.’

I said I’d revoke the order.

‘That, unfortunately,’ he replied, shaking his head gloomily, ‘is impossible. Or very difficult. Or highly inadvisable. Or would require legislation. One of those. But in any case it could not invalidate an action taken while the order was in force.’

As I contemplated this dubious explanation, Mrs Phillips burst in.

She was in full Wagnerian voice. ‘I don’t care if he’s talking to the Queen and the Pope,’ she shouted at some poor Executive Officer outside my door. She strode across the room towards me. ‘Judas,’ was her initial greeting.

‘Steady on,’ I replied firmly.

‘You promised to support us,’ she snarled.

‘Well, yes, I did,’ I was forced to admit.

‘Then you must see that our lease is renewed.’

Sir Humphrey tried to intervene between us. ‘Unfortunately, dear lady, it is not in my Minister’s power to . . .’

She ignored him and said to me: ‘Mr Hacker, you have given your word. Are you going to keep it?’

Put like that, I was in a bit of a spot. I did my best to blur the issue.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘in that, well, I shall certainly . . . you know, I didn’t exactly give my word, that is, I shall explore all the avenues, make every effort, do all that is humanly possible —’ Words to that effect.

Mrs Phillips was no fool. ‘You mean no!’ she said.

I was quite honestly stuck for a reply. I said ‘No,’ then that seemed a little unambiguous so I said ‘No, I mean Yes,’ then that seemed dangerous so I added that by no I didn’t mean no, not definitely not, no.

Then – another bombshell! ‘Don’t say I didn’t warn you,’ she said. ‘My husband is deputy features editor of the

Express

. Tomorrow morning your name will be manure. You will be roasted alive by the whole of the national press.’

Express

. Tomorrow morning your name will be manure. You will be roasted alive by the whole of the national press.’

The room fell silent after she swept out and slammed the door. An intense gloom had descended upon the assembled company – or upon me, anyway. Finally, Sir Humphrey found his voice: ‘It falls to few people,’ he said encouragingly, ‘to be within twenty-four hours both St Francis and St Joan.’

I have got to stop this farm being closed. But how? Clearly I’m going to get no help from my Permanent Secretary.

September 21st

No story in the

Express

today, which was a slight relief. But I couldn’t believe they’ll let it pass.

Express

today, which was a slight relief. But I couldn’t believe they’ll let it pass.

And when I got to the office there was a message asking me to call that wretched rag.

Also, a message that Sir Desmond wanted to see me urgently. I suggested a meeting next week to Bernard, but it seemed that he was downstairs waiting! Astonishing.

So Bernard let him in. Humphrey appeared as well.

When we were all gathered, Glazebrook said he’d just had an idea. For nine storeys extra on his bank! I was about to boot him out when he explained that if they had nine more storeys the bank could postpone Phase III for seven years. This would leave a site vacant.

‘So?’ I was not getting his drift.

‘Well,’ he said. ‘I was reading in the

Financial Times

a day or two ago about your visit to that City Farm. Thought it was a jolly good wheeze. And, you see, our Phase III site is only two hundred yards away from it, so you could use it to extend the farm. Or if they wanted to move . . . for any reason . . . it’s actually a bit bigger . . . We thought of calling it the James Hacker Cuddly Animal Sanctuary . . .’ (he and Humphrey exchanged looks) ‘well, Animal Sanctuary anyway, and nine storeys isn’t really very much is it?’

Financial Times

a day or two ago about your visit to that City Farm. Thought it was a jolly good wheeze. And, you see, our Phase III site is only two hundred yards away from it, so you could use it to extend the farm. Or if they wanted to move . . . for any reason . . . it’s actually a bit bigger . . . We thought of calling it the James Hacker Cuddly Animal Sanctuary . . .’ (he and Humphrey exchanged looks) ‘well, Animal Sanctuary anyway, and nine storeys isn’t really very much is it?’

It was clear that they were in cahoots. But it was, unmistakably, a way out. If I gave them permission for a high-rise bank, they’d enable the City Farm to stay open.

It is incredible, I thought, that I should ever have thought that Humphrey would take my side against his old chum Glazebrook. And yet, Glazebrook is not really Humphrey’s type. He must be holding something over Humphrey . . . I wonder what.

Meanwhile, I had to think up some valid reasons for approving the high-rise building – and quickly. The official application wouldn’t be in for a while but in front of Bernard I felt I had to come up with some face-saving explanations. Fortunately, everyone pitched in.

‘You know, Humphrey,’ I began, ‘I think the government has to be very careful about throttling small businesses.’

Bernard said, ‘The bank’s not actually a small business.’

‘It will be if we throttle it,’ I said firmly, squashing him. He looked puzzled. ‘Bernard,’ I said casually, ‘what’s one more skyscraper when there’s so many already?’

‘Quite so,’ agreed Sir Humphrey.

‘And let’s announce it right away,’ I continued.

So we all agreed that the high-rise building will cut both ways. It will create shade for the school. Extra revenue for the public transport system. And as for privacy – well, it could be fun for people in their gardens to look up and see what’s going on in the offices. Couldn’t it?

‘After all,’ I added meaningfully, ‘some extraordinary things go on in offices, don’t they Humphrey?’

He had the grace to smile. ‘Yes Minister,’ he agreed.

1

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

2

One of Hacker’s rare jokes.

One of Hacker’s rare jokes.

3

In conversation with the Editors.

In conversation with the Editors.

14

A Question of Loyalty

September 27th

I’m due to go to Washington tomorrow for an official visit. I should have thought that it wasn’t strictly necessary for me to be away for a whole week but Sir Humphrey insists that it’s of enormous value if I stay there for an appreciable time so as to get the maximum diplomatic benefit from it all.

I’m to address a conference on administration. One of the Assistant Secretaries, Peter Wilkinson, has written me an excellent speech. It contains phrases like ‘British Government Administration is a model of loyalty, integrity and efficiency. There is a ruthless war on waste. We are cutting bureaucracy to the bone. A lesson that Britain can teach the world.’ Good dynamic stuff.

However, I asked Humphrey yesterday if we could prove that all of this is true. He replied that a good speech isn’t one where we can prove that we’re telling the truth – it’s one where nobody else can prove we’re lying.

Good thinking!

I hope the speech is fully reported in the London papers.

SIR BERNARD WOOLLEY RECALLS:

1

1

I well remember that Sir Humphrey Appleby was extremely keen for Hacker to go off on some official junket somewhere. Anywhere.

He felt that Hacker was beginning to get too much of a grip on the job. This pleased me because it made my job easier, but caused great anxiety to Sir Humphrey.

I was actually rather sorry to have missed the Washington junket, but Sir Humphrey had insisted that Hacker take one of the Assistant Private Secretaries, who needed to be given some experience of responsibility.

When he’d been away for five or six days I was summoned to Sir Humphrey’s office. He asked me how I was enjoying having my Minister out of the office for a week, and I – rather naïvely – remarked that it made things a little difficult.

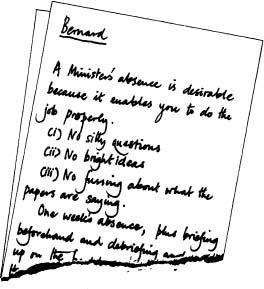

It was instantly clear that I had blotted my copybook. That afternoon I received a memo in Sir Humphrey’s handwriting, informing me of the benefits of ministerial absence and asking me to commit them to memory.

[

Fortunately Sir Bernard kept this memo among his personal papers, and we reproduce it here, written on Sir Humphrey’s margin-shaped notepaper – Ed

.]

Fortunately Sir Bernard kept this memo among his personal papers, and we reproduce it here, written on Sir Humphrey’s margin-shaped notepaper – Ed

.]

Bernard

A Minister’s absence is desirable because it enables you to do the job properly.

(i) No silly questions

(ii) No bright ideas

(iii) No fussing about what the papers are saying.

One week’s absence, plus briefing beforehand and debriefing and catching up on the backlog on his return, means that he can be kept out of the Department’s hair for virtually a fortnight

Furthermore, a Minister’s absence is the best cover for not informing the Minister when it is not desirable to do so – and for the next six months, if he complains of not having been informed about something, tell him it came up while he was away

[

Sir Bernard continued – Ed

.]

Sir Bernard continued – Ed

.]

Anyway, the reason behind the increasing number of summit conferences that took place during the 1970s and 1980s was that the Civil Service felt that this was the only way that the country worked. Concentrate all the power at Number Ten and then send the Prime Minister away – to EEC summits, NATO summits, Commonwealth summits, anywhere! Then the Cabinet Secretary could get on with the task of running the country properly.

At the same meeting we discussed the speech that Peter had written for the Minister to deliver in Washington.

I suggested that, although Peter was a frightfully good chap and had probably done a frightfully good job on it in one way, there was a danger that the speech might prove frightfully boring for the audience.

Sir Humphrey agreed instantly. He thought that it would bore the pants off the audience, and it must have been ghastly to have to sit through it.

Nonetheless, he explained to me that it was an excellent speech. I learned that speeches are not written for the audience to which they are delivered. Delivering the speech is merely the formality that has to be gone through in order to get the press release into the newspapers.

‘We can’t worry about entertaining people,’ he explained to me. ‘We’re not scriptwriters for a comedian – well, not a professional comedian, anyway.’

He emphasised that the value of the speech was that it said the correct things. In public. Once that speech has been reported in print, the Minister is committed to defending the Civil Service in front of Select Committees.

I sprang to the Minister’s defence, and said that he defends us anyway. Sir Humphrey looked at me with pity and remarked that he certainly does so when it suits him – but, when things go wrong, a Minister’s first instinct is to rat on his department.

Therefore, the Civil Service when drafting a Minister’s speech is primarily concerned with making him nail his trousers to the mast. Not his colours, but his trousers – then he can’t climb down!

As always, Sir Humphrey’s reasoning proved to be correct – but, as was so often the case, he reckoned without Hacker’s gift for low cunning.

Other books

The Becoming: Ground Zero by Jessica Meigs, Permuted Press

Warning Signs (Broken Promises #2) by Alexandra Moore

The Anarchists by Thompson, Brian

Quake by Jacob Chance

Eighty Days Red by Vina Jackson

Trust by J. C. Valentine

A Promise Kept by Anissa Garcia

Stab in the Dark by Louis Trimble

Healer (The Healer Series) by B.N. Toler

ARC: Under Nameless Stars by Christian Schoon