The Conquering Tide (16 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

I

N TWO PREVIOUS CARRIER DUELS,

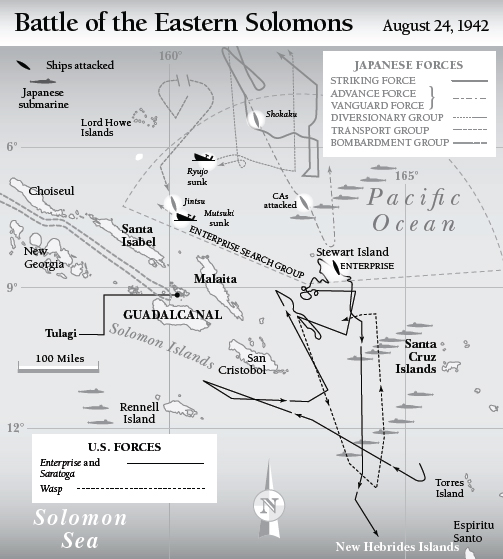

Frank Jack Fletcher had enjoyed timely intelligence about the enemy's plans. Now the picture was murkier. The Japanese had updated their naval code again on August 13, setting the cryptanalysts back by several weeks. Radio traffic analysis had detected the southward movement of naval forces from Japan's home waters to Truk, which might presage a move into the lower Solomons, but the Americans lacked hard evidence of the whereabouts of the Japanese carriers. Commander Joseph Rochefort, chief of Pearl Harbor's codebreaking unit, who had set up the American victory at Midway, believed they were in Japan's Inland Sea.

49

No data had emerged to challenge that theory, and if Nagumo's task force was practicing good radio discipline, it might have moved south to Truk or even into the Solomons. Ghormley radioed Fletcher on August 22: “Indications point strongly to enemy attack in force

CACTUS

area 23â26 August.” COMSOPAC believed the enemy fleet might include one or two battleships, fifteen cruisers, and many destroyers: “Presence of carriers possible but not confirmed.”

50

Since his withdrawal on August 9, Fletcher's mandate had been to fly cover over the sea-lanes linking bases in New Caledonia and the New Hebrides to the Solomons, and to assist in transferring aircraft to Henderson Field. He had taken care to keep his ships well fueled, in case of any sudden contingency. Receiving news of the Japanese ground attack on the Tenaru

River, he turned north on the night of August 19â20 and advanced to an aggressively far northwest position, just east of the island of Malaita. But radio intelligence continued to posit that the Japanese carriers remained at Truk, more than 1,000 miles northwestâand if that was so, the earliest they could be expected to give battle was August 25. Fletcher, supposing he had a two-day refueling window, sent the

Wasp

and her escorts south to rendezvous with a fleet oiler. As it happened, she would not return in time to join the impending battle.

On August 22 and 23, as each combatant probed for the other, the skies above the region were congested with reconnaissance planes. Admiral McCain's PBYs and B-17s flew long missions from Espiritu Santo; marine dive-bombers spread out from Henderson Field; six more PBYs operated from a lagoon on Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands. From Rabaul, big four-engine Kawanishi flying boats radiated out in 700-mile search vectors to the south and east.

51

On August 22, shortly before 11:00 a.m., the

Enterprise

radar scope picked up a blip to the southwest. Four fighters were sent to investigate. They tracked a Kawanishi and quickly sent it down in flames.

The next morning brought a confusing flood of contact reports. PBYs from Ndeni reported a column of four transports escorted by four destroyers east of Bougainville Island, about 300 miles north of Guadalcanal. This was Tanaka's occupation force. Aware that he had been snooped, and fearing a punishing air attack on his vulnerable transports, Tanaka turned north. Radioing from his flagship

Yamato

, Admiral Yamamoto ordered Nagumo to send the “Diversionary Force”âlight carrier

Ryujo

, heavy cruiser

Tone

, destroyers

Amatsukaze

and

Tokitsukaze

âto race south and attack Henderson Field the following morning. The scheduled date for Tanaka's troop landings was pushed back to August 25.

With the PBYs' sighting report in hand, Fletcher launched a powerful strike from the

Saratoga

, thirty-one dive-bombers and six TBF Avenger torpedo planes, to attack Tanaka's column. Commander Harry D. Felt, the

Saratoga

air group commander, led the flight. They were joined en route by another nine SBDs, one TBF, and thirteen fighters from Henderson Field. The formation ran into a wall of impenetrable wet white haze. Felt arrayed his planes by sections in a line abreast, flying just 50 feet above the sea. No one could see anything but the sea below and the planes on either side. “We must have flown in this stuff for an hour,” Felt remembered, “and all of a

sudden, broke through into an open area, and there was the whole damned group right there. Just magnificent discipline!”

52

Tanaka having dodged north to avoid just this attack, Felt and his squadrons found no sign of the enemy fleet. The

Saratoga

planes followed the marine planes back to Guadalcanal, where they managed to land on the muddy field in the failing light. The exhausted

Saratoga

pilots spent the night in their cockpits, ready to take off at dawn.

The two carrier forces were mutually blind. They were only 300 miles apart, just beyond extreme air-striking range, but neither had pinpointed the other's location. Between 5:55 and 6:30 a.m. on August 24, the

Enterprise

launched twenty-three SBDs. From the carrier's position, 200 miles east of Malaita, they fanned out in a 120-degree arc to the north and west. The PBYs at Ndeni were also in the air before first light. The Japanese fleet, converging on Guadalcanal from the west, was still just beyond the edges of the American morning search, and none of the

Enterprise

planes reported a contact. But one of McCain's PBYs spotted the

Ryujo

force roaring south at 9:05 a.m., and another found the heavy surface warships of Kondo and Abe's force half an hour later.

Now Fletcher faced a dilemma. Should he pounce on the

Ryujo

, or should he keep his powder dry, hoping for word of the big carriers? The PBY's report had put the

Ryujo

275 miles north of Tulagi, a long flight of about 250 miles from the

Saratoga

âbut if the target kept her southerly course, she would come closer. When Felt's planes returned from Guadalcanal, landing at 11:00 a.m., Felt told the admiral that his pilots were dog-tired and could use a rest. “You keep getting intelligence and when those things are within our range, we'll go,” he suggested.

53

Fletcher assented. At 11:38 a.m., another PBY reported the

Ryujo

force, this time farther south.

Confronted with a mass of conflicting and uncertain data, and with so much at stake, Fletcher hesitated to make a precipitous decision. Shortly after noon, he assigned the

Enterprise

air group to conduct a search to the northwest to a distance of 250 miles. Sixteen SBDs and seven TBFs departed the carrier at 1:15. In short order, Charlie Jett of VT-3 found the

Ryujo

and radioed back a contact report. Jett and a wingman attempted a horizontal bombing attack at 12,000 feet. Dropping bombs from altitude on ships maneuvering at speed was usually futile, and this was no exception. They missed and turned back toward the American task force.

Still having heard nothing about the enemy's big carriers, Fletcher

elected to commit his reserve strike to finish the little

Ryujo

. Twenty-eight SBDs and eight TBFs led by Commander Felt flew a heading of 320 degrees. By that time,

Ryujo

had already launched six Nakajima B5N “Kates” and fifteen Zeros against Henderson Field. Marine fighters defended the airfield in a pitched dogfight over the island, downing three Nakajimas and three Zeros, losing only three American aircraft in the melee. (Bombers from Rabaul were supposed to have arrived over the target at about the same time, but thick weather had forced them back to base.) Importantly, the

Ryujo

planes did not do any significant damage to the marine installations around Henderson or to the airfield itself.

54

At 3:36 p.m., the

Saratoga

strike closed in on the

Ryujo

. She went into a tight starboard turn and continued to circle throughout the attack. One after another, the dive-bombers rolled into their dives and released their bombs. Several missed close aboard, but Felt personally planted the first of three 500-pound bombs on the flight deck, and one of the TBFs sent a torpedo into her starboard side. The attack, said Felt, “was carried out just like a training exercise.”

55

The

Ryujo

was soon blazing out of control while still circling clockwise. From the air, Felt observed her “pouring forth black smoke which would die down and then belch forth in great volume again.”

56

She was abandoned by her crew, most of whom simply leapt over the side. The skipper of the destroyer

Amatsukaze

watched the blazing wreck through his binoculars. “A heavy starboard list exposed her red belly,” he recalled. “Waves washed her flight deck. It was a pathetic sight.

Ryujo

, no longer resembling a ship, was a huge stove, full of holes which belched eerie red flames.”

57

A total loss, she would be scuttled four hours later. Her returning planes were forced to ditch at sea.

Meanwhile, a cruiser scout from the

Chikuma

sighted the two American carriers at 2:30 p.m. The sluggish floatplane was shot down by

Enterprise

fighters, but not before the pilot managed to get a transmission off to Nagumo. Radio direction-finding gear on the

Shokaku

gave the Japanese an accurate bearing to the doomed plane, and thus to the American task force. Nagumo now held the advantage. He had not yet been discovered, but he had pinpointed Fletcher's position, and it was well within striking range. At 2:55 p.m., the first of two big strikes took off from the

Shokaku

and

Zuikaku

: twenty-seven Aichi D3A2 “Vals” escorted by fifteen Zeros.

As the planes left the decks, two

Enterprise

SBDs caught sight of the Japanese carriers and radioed a report to Fletcher. The American communications

were very poor, however: the airwaves were clogged by heavy static and gratuitous pilot chatter, and the admiral received no word of the contact until more than an hour later. The two SBDs dived and bravely attacked the

Shokaku

, but missed. About an hour after the first wave, Nagumo launched a second wave of twenty-seven Aichis and nine Zeros.

Now Fletcher had two large waves of enemy dive-bombers incoming, and had not yet replied. When the contact report belatedly got through to him, he realized he may have repeated the error he had committed three and a half months earlier in the Battle of the Coral Seaâaiming his strike at a small carrier when the enemy's big carriers were still in the vicinity. He tried to redirect the outbound flight, but was again defeated by feeble radio communications. As one

Enterprise

dive-bomber pilot ruefully observed, “We had been outsmarted strategically with the tactical battle still to be foughtâit was Coral Sea all over again.”

58

The

Enterprise

radar plot detected the first wave of incoming planes at 4:32 p.m., when they were eighty-eight miles to the northwest.

59

F4F Wildcats roared off both flight decks and “dangled on their propellers” (climbed at maximum speed), their 1,200-horsepower Pratt & Whitney radial engines straining mightily. The Japanese now enjoyed the tactical upper hand. A broken cloud ceiling gave them good visual cover.

60

Knowing that the F4Fs were slow climbers, the attackers approached at abnormally high altitudes, between 18,000 and 24,000 feet. After the initial radar return, the American scopes went dark for seventeen minutes, and when they lit up again at 4:49, the leading edge of the enemy wave was only forty-four miles away. American fighters were diverted by the escorting Zeros, allowing most of the dive-bombers to slip through the screen unmolested. The

Enterprise

's fighter director officer (FDO) struggled to get through to his pilots while the radio circuit was congested with their chatter: “Look at that one go down!” and “Bill, where are you?”

61

(Captain Arthur C. Davis of the

Enterprise

later observed, “The air was so jammed with these unnecessary transmissions that in spite of numerous attempts to quiet the pilots, few directions reached our fighters and little information was received by the Fighter Director Officer.”)

62

Both carriers rang up maximum speed for evasive maneuvering and turned southeast in order to bring wind across their decks for flight operations. All strike planes spotted on deck were ordered to launch. The pilots were simply told to get away, to clear the areaâit was not that important where they went, so long as they were not on deck when the enemy

dive-bombers hurtled down from overhead. If both flattops went down, or were damaged and incapable of landing planes, they could fly to Henderson Field on Guadalcanal. Once aloft, the

Enterprise

and

Saratoga

strike planes were instructed by radio to head northwest in search of the big twins

Zuikaku

and

Shokaku

. With only two hours of daylight remaining, their odds of attacking the enemy and returning safely were very long.

At 5:09, the

Enterprise

radar plot informed the captain that “the enemy planes are directly overhead now!”

63

The antiaircraft gunners, with helmets pushed back on their heads and kapok life vests drawn up tight around their necks, studied the sky. For a moment, nothing seemed amiss. The afternoon was absurdly peaceful. A few black specks moved above and

between the high, thin wisps of cloud. Then a few of those specks stopped and seemed to fix in place. Gradually, the rising drone of aircraft engines could be heard. The larger specks began to take shapeâa blurred disk, bisected by wings, with fixed landing gear under the wings, sun glinting off the cockpit canopies, and a second, smaller speck (the bomb) tucked under the fuselage. Witnesses who had never seen a dive-bombing attack were surprised at how long the enemy planes took to come down. They dived at angles of 70 degrees or even steeper, most on the port beam and quarter of the

Enterprise

. The attack, according to Captain Davis, was “well executed and absolutely determined.”

64