The Conquering Tide (82 page)

Read The Conquering Tide Online

Authors: Ian W. Toll

O

N THE MORNING OF

J

UNE 13

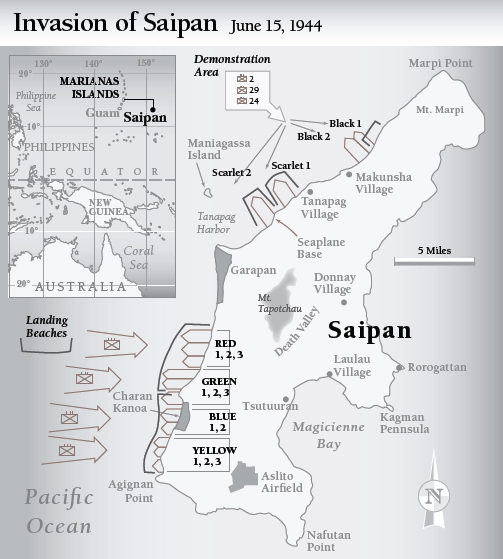

, forty-eight hours before the first scheduled landings, the first bombardment group arrived off Saipan and Tinian. It included seven new “fast” battleships under the command of Vice Admiral Willis A. “Ching” Lee, detached from Task Force 58 to make an early start of working over Saipan's beach defenses, accompanied by about a dozen destroyers. The group rained 16- and 5-inch high-explosive shells down on the zones immediately inland of the landing beaches, and for all appearances the entire area was left a smoking ruin. For fear of mines on the ocean shelf, Lee's battleships remained at long range, 10,000 to 16,000 yards. The destroyers drew in close to shore and concentrated their guns on both islands' barracks and bivouac areas.

13

Under the cover provided by the barrage, six minesweepers swept the waters off the landing beaches. No mines were found. On June 14, two 96-man Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) were transported to the edge of the fringing reef. Frogmen swam in close under the Japanese shore artillery, charted the reef, and determined the lanes that the landing craft should take the following day. The divers found no artificial beach obstructions. They blasted out coral heads to clear paths for the landing craft. Under fire by artillery on shore, the demolition teams lost four men killed and five wounded.

The weather was beautiful, very sunny and bright, almost blindingly soâbut the breeze was constant and the air was pleasantly dry. On the transport fleet, approaching from the east, the landing troops found that they were able to sleep far better than they had in the South Pacific. Men dozed on deck, some in sun and some in shade; men wrote letters, played cards and checkers, tossed a medicine ball for exercise. Carrier planes patrolled overhead throughout the daylight hours. The sheer size of the fleet was a balm to their spirits. On many ships, the radio chatter between the planes above Saipan

and the battleships offshore was piped through the ships' loudspeakers, allowing the men aboard to form a mental picture of the action. Scale plaster models of Saipan were laid out on wardroom tables, with the locations of landing beaches, airfields, towns, and known shore batteries marked in colored ink.

On the night before D-Day, the 2nd Division marines scrubbed themselves and their dungarees. They arose well before dawn and ate a hearty breakfast. The island now loomed off the starboard bow. The flat snub cone of Mount Tapotchau was barely discernible against the slightly lighter sky, but patches of the island were now and again illuminated by muzzle flashes or star shells. The fire support group, commanded by Rear Admiral Kingman, rendezvoused with the amphibious assault group under Admiral Turner. At first light the enormous fleet, numbering several hundred vessels, moved into assigned stations. The big guns put on a typically majestic show as they blasted the shore defenses. Sailors began lowering the landing craft. The marines, noted combat correspondent Pete Zurlinden, seemed relaxed and even bored as they watched the naval guns and carrier bombers spread destruction along the shore. They sorted through their gear one last time and sighted along their rifles. Virtually all of the noncommissioned officers were veterans of previous amphibious assaults. “To most of them,” wrote Zurlinden

,

“this is an old story. . . . They are quiet, laconic in their conversation.”

14

They had seen and done it before.

From his flagship

Rocky Mount

, Admiral Turner raised the signal “Land the Landing Force.” At 8:13 a.m., the force control officer signaled the first-wave landing boats to gather behind the line of departure, 4,000 yards offshore. The assault beaches were spread along a four-mile front to the north and south of Charan Kanoa, a sugar refinery and village on the southern part of the leeward coast. The boats motored toward shore in a line abreast, LVTs crammed with troops and accompanied by armed and armored amtracs, gunboats, and army DUKWs (amphibious trucks). Those first boats got ashore with few casualties, and within eight minutes marines had a foothold on every landing beach. The second and third waves followed close behind. Machine-gun fire was heavy above the southernmost landing beaches, designated Yellow 1 and Yellow 2. There the marines were pinned down for more than an hour, and could do nothing but dig into the sand. A larger-than-expected western swell broke over the reef and overturned boats loaded with ammunition, machine guns, light artillery pieces, and drinking water.

As they reached the reef, about 1,000 yards from shore, the fourth and fifth waves were under intense artillery and mortar fire. The weapons, positioned on ridges above the beaches, had been registered to hit the reefs, and when they opened up, the entire reef line seemed to erupt in a barricade of whitewater and flames. This first salvo was so closely timed that witnesses offshore assumed a series of mines must have been detonated by one signal. A few craft took direct hits and suffered 100 percent casualties. But the American fleet was very generously supplied with landing craft, more than 800 altogether, and enough got through to deliver 8,000 men to the beaches in the first twenty minutes.

For the remainder of that critical first day, the marines concentrated on holding the beaches and getting more men, equipment, and weaponry ashore. Seven battalions of artillery (75mm and 105mm howitzers) and two tank companies landed in the afternoon. Twenty thousand marines were ashore by the end of the day. Japanese artillery and mortar fire remained unrelenting throughout. Marines employed shell craters as makeshift foxholes and continually deepened them as the barrage continued and intensified. Direct hits claimed many lives. Five battalion commanders were wounded and evacuated; one battalion lost three commanders in quick succession. Lieutenant Robert B. Sheeks was crawling up the beach when a mortar shell hit two marines immediately to his left. “There was an explosion and these two guys just evaporated. We couldn't see any sign of them. They were disintegrated, just mixed in with the sand and vegetation and scattered all over the place.”

15

The naval bombardment had succeeded in knocking out most of the big coastal guns and in pulverizing some of the larger fixed fortifications that were easily seen from the offing or from planes overhead. But General Saito's forces had effectively concealed smaller mobile artillery pieces and mortars in the high ground inland of the beaches. Holland Smith gradually ascertained that Japanese troop strength on the island was about 40 to 50 percent higher than anticipated by intelligence estimates. By nightfall the marines had penetrated about 1,500 yards inland at the deepest point in their perimeter. Their artillery could not yet effectively reach the enemy, who was tucked behind the ridgeline, but the carrier bombers aimed their bombs and machine guns at the muzzle flashes, and the naval guns began to find the range, helped by aerial spotting floatplanes. On the morning of June 16, heavy fighting continued all along the perimeter. American casualties

surpassed 2,500. Smith requested all available reinforcements and recommended that the invasion of Guam, previously scheduled for June 18, be indefinitely postponed.

Smith pressured his division and battalion commanders to move inland, but the terrain above the beach impeded most of the tanks and armored vehicles, and there were few suitable footpaths allowing for rapid infantry movements. On the afternoon of June 16, most of the 27th Division was landed. Smith intended to send the soldiers across relatively accessible terrain toward the southeastern part of the island, where they would capture Aslito Airfield.

On June 16, Saito decided to commit his reserves to a night counterattack

on the northern flank of the 2nd Marine Division, near the northern limit of the American perimeter. The Japanese made no special effort to conceal their intentions. On the fleet offshore, sailors watched as Japanese troops rallied in the town of Garipan and aroused their sprits with “parades, patriotic speeches and much flag waving.”

16

At 8:00 p.m., about forty light tanks and two columns of infantry advanced south along the coast road. Their approach was easily tracked by ships offshore. Star shells kept them brightly illuminated. Naval gunfire caught the tanks at an exposed point and destroyed about twenty of the machines. Marines took the attackers under fire with machine guns and 75mm howitzers, and a close melee ensued, with heavy losses on both sides, but especially to the attackers. The Japanese army rallied and attempted several more attacks in the early morning hours, but the marines held their positions and destroyed the remaining tanks with field artillery, infantry antitank weapons, and bazookas.

Corpsmen set up stations on the beach to treat the wounded. It proved impossible to shield them from the relentless mortar fire. Private Richard King described the macabre scene in a letter to his parents: “All along the beach, men were dying of wounds. Maybe you will think this is cruel, but I want you to know what it was like. Mortar shells dropping in on heads, and ripping bodies. Faces blown apart by flying lead and coral. It wasn't a pretty sight, and I will never forget the death and hell along that beach. It rained all the night and mud was ankle deep.”

17

The failure of Saito's all-out counterattack shifted the momentum to the invaders. On June 17, marines pushed inland and overran many of the artillery batteries that had inflicted such misery for three days. The 4th Division marines and the 27th Division soldiers broke through in the south and pushed all the way to Magicienne Bay, bisecting the island and cutting off the remaining Japanese in the south. Aslito Airfield was secured on June 18. The 4th Division was now poised to swing north and begin driving the remaining Japanese forces back

into the northern half of the island.

On June 18 at 10:00 a.m., Smith went ashore and established his Fifth Amphibious Corps headquarters in the ruins of Charan Kanoa. The big sugar refinery that dominated the town was a smoking ruin, except for its blacked smokestack, which had somehow survived. Railroad cars had been scattered across the tracks. Japanese resistance was weakening, at least on the ridges behind the position, but the remaining forces were pulling back into the northern half of the island. From his new vantage point ashore, Smith looked out at the fleet and noted that it was considerably smaller than it had been. Spruance had detached most of the warships, including two cruiser divisions and several destroyer divisions, to rendezvous with Mitscher and Task Force 58 in anticipation of a major fleet battle west of the Marianas. The transports had withdrawn to the east, to avoid losses by air attack.

Smith knew that the enemy fleet must be met and destroyed, and that the warships were protecting his beachhead even if they lay beyond the horizon. But the sight of a powerful fleet offshore weighed in the psychological attitudes of the contending forces. Smith frankly told his staff officers that he was concerned that its sudden disappearance would prompt a surge in the morale of enemy ground forces.

T

HE

F

IRST

M

OBILE

F

LEET HAD PAUSED

in Guimaras Strait to take on 10,800 tons of fuel. It passed through the Visayan Sea and into the San Bernardino Strait (between Luzon and Samar). As night fell on June 15, the great fleet emerged into the Philippine Sea.

Ozawa correctly surmised that his movements had been tracked by American submarines since his departure from Tawi Tawi. He had intercepted coded radio transmissions likely alerting Pearl Harbor to his whereabouts. Large signal fires were seen on the peaks along the coast south of San Bernardino Strait, where pro-American guerrillas regularly reported ship movements to the enemy. Ugaki's force of battleships and cruisers, having broken off the attack on Biak and sailed north past Halmahera, had been shadowed by enemy long-range bombers. The Japanese fleet was not going to take the enemy by surprise.

Fuel was a stringent consideration. The navy had allocated seven precious oilers to get the First Mobile Fleet this far. They were filled with the crude Borneo petroleum that degraded the performance of the ship's boilers and was volatile and potentially dangerous to handle. Given the constraints, Ozawa had managed his fueling situation exceptionally well, but he had little margin for unexpected developments. He could bring his carriers within striking range of the Marianas, but would have to withdraw to the Inland Sea immediately after the battle.

Ugaki's warships fell in with Ozawa's force on June 16. Refueling continued

throughout the following night. With tanks topped off, the fleet steamed east. The officers and men of the First Mobile Fleet sensed that they were on the verge of making history. “This operation has an immense bearing on the fate of the Empire,” Ozawa signaled the fleet. “It is hoped that all forces will do their utmost and attain results as magnificent as those achieved in the Battle of Tsushima.”

18

The first part of the message was incontrovertible; the second was merely a hope, and a forlorn one. Postwar interrogations and Ugaki's contemporary diary entries leave no doubt that senior commanders were concerned about the fleet's readiness for battle, and that the aviators were badly overmatched. They fastened their hopes to their tactical advantages, of which there were more than a few. For all the wartime tribulations of the Japanese aircraft industry, the new-generation carrier bombers could fly some 200 miles farther than their American counterparts. Because the Japanese still possessed airfields on Guam and other islands, their carrier planes could (in theory) strike the American fleet, refuel and rearm at the airfields, and then give the Americans another working-over before returning to their carriers. If all went as planned, this “shuttle-bombing” tactic might enable Ozawa to strike the enemy twice while his carriers remained out of range. The Japanese now possessed accurate knowledge of the composition and location of the American fleet, so there would be no unpleasant surprises as at Midway. The trade wind from the east worked in favor of the Japanese, as it would require the Americans to move east into the wind to conduct flight operations. Possession of the “lee-gauge” gave Ozawa the power to control the timing of events, and would severely constrain the Americans' ability to give chase to the west. Turner's amphibious fleet, tethered to the Saipan beachhead, lacked tactical mobility. The land-based air forces of the Marianas might yet mete out retribution to the American fleet, or so it was hopedâOzawa had not yet learned how badly Kakuta's air units had been mauled, perhaps because the latter was reluctant to admit it. Insofar as Ozawa knew, Kakuta's airmen had delivered a week's worth of hard knocks on the American fleet and its carrier air groups. He assumed that the airfields on Guam and Rota were prepared to receive and turn around his carrier planes as planned.