The Cradle in the Grave (28 page)

Read The Cradle in the Grave Online

Authors: Sophie Hannah

âHe had a point,' she says gently. âIf all the mothers convicted of killing their babies appeal and win, the message is clear: mothers don't and can't murder their children. Which we all know isn't true.'

âHe started shouting in front of everybody.' I'm crying again, but this time I don't care. â“Suddenly, they're all innocent â Yardley, Jaggard, Hines! All tried for murder, two of them convicted, but they're all innocent! How can that be?” He was yelling at me and Mum, as if it was our fault. Mum couldn't handle it, she ran out of the restaurant. I said, “Dad, no one's saying Rachel Hines is innocent. You don't know she's going to appeal, and even if she does, you don't know she'll win.”'

âHe was right.' Rachel stands up, starts to walk in no particular direction. She would hate my kitchen. It's too small for aimless walking. It would make her feel sick. âMy case effectively changed the law. Like your dad, the three judges who heard my appeal didn't see me as an individual. They saw me as number three, after Yardley and Jaggard. Everyone lumped us together â the three crib death killers.' She frowns. âI don't know why we got to be the famous ones. Lots of women are in prison for killing children, their own and other people's.'

I think of Laurie's article.

Helen Yardley, Lorna Keast, Joanne Bew, Sarah Jaggard, Dorne Llewellyn . . . the list goes on and on

.

Helen Yardley, Lorna Keast, Joanne Bew, Sarah Jaggard, Dorne Llewellyn . . . the list goes on and on

.

âWould I have had my convictions overturned if Helen Yardley hadn't set a precedent? She was the one who first piqued Laurie Nattrass's interest. It was her case that made him start questioning Judith Duffy's professionalism, which was what led to my being granted leave to appeal.' She turns to face me, angry. âIt was nothing to do with me. It was Helen Yardley, Laurie Nattrass and JIPAC. They turned it political. It wasn't about our specific cases any more â Sarah Jaggard's, mine. We weren't individuals, we were a national scandal: the victims of an evil doctor who wanted us locked up for ever. And her motive? Rampant malevolence, because we all know some doctors

are

evil. Oh, we're all suckers for a wicked doctor story, and Laurie Nattrass is a brilliant storyteller. That's why the prosecution rolled over and I was spared a retrial.'

are

evil. Oh, we're all suckers for a wicked doctor story, and Laurie Nattrass is a brilliant storyteller. That's why the prosecution rolled over and I was spared a retrial.'

âBecause Laurie can't see the trees for the wood.'

âWhat? What did you say?' She's standing over me, leaning down.

âMy boss, Mayaâshe said you said that about him. She thought you'd got the saying wrong, but you meant it the way you said it, didn't you? You meant to say that Laurie saw you as one of his wrongly accused victims, not as a person in your own right. That's why you want the documentary to be about you onlyânot Helen Yardley or Sarah Jaggard.'

Rachel kneels down on the sofa beside me. âNever underestimate the differences between things, Fliss: your flat in a horrible terrace in Kilburn and this house; a beautiful painting and a soulless mass-produced image of an urn; people who are capable of seeing only their own narrow perspective, and people who see the whole picture.' She's pinching the skin on her neck again, turning it red. Her eyes are sharp when she turns to face me. âI see the whole picture. I think you do too.'

âThere's another reason,' I say, my rapid heartbeat alerting me to the inadvisability of bringing this up.

Tough

. Now that I've had the thought, I have to see her reaction. âThere's another reason you don't want to be part of the same programme as Helen Yardley and Sarah Jaggard. You think they're both guilty.'

Tough

. Now that I've had the thought, I have to see her reaction. âThere's another reason you don't want to be part of the same programme as Helen Yardley and Sarah Jaggard. You think they're both guilty.'

âYou're wrong. I don't think that, not about either of them.' When she speaks again, her voice is thick with emotion. âYou're as wrong about me as I'm right about you, but you're thinking â that's what matters. If I wasn't convinced before, I am now: it has to be you, Fliss. You have to make this documentary. The story needs to be told and it needs to be told now, before . . .' She stops, shakes her head.

âYou said your case changed the law,' I say, trying to sound professional. âWhat did you mean?'

She snorts dismissively, rubbing the end of her nose. âMy appeal judges concluded, and wrote into their summary remarks so that there would be no ambiguity, that when a case relies solely on disputed medical evidence, that case should not be brought before a criminal court. Which means it's now pretty much impossible to convict a mother who waits till she's alone with her child and then smothers him. There isn't generally much other evidence in cases of smothering. The victim puts up no resistance, being only a baby, and there are no witnesses â you'd have to be pretty stupid to try to smother your baby in front of a witness.'

Or desperate, I think. So desperate you don't care who sees.

âYour father's prediction was spot on. My appeal judgement

has

made it easier for mothers to murder their babies and avoid prosecution. Not only mothers â fathers, childminders, anyone. Your dad was smart to see it coming. I didn't. I might not have appealed if I'd known that was the effect it would have. I'd lost everything already. What did it matter if I was in prison or out?'

has

made it easier for mothers to murder their babies and avoid prosecution. Not only mothers â fathers, childminders, anyone. Your dad was smart to see it coming. I didn't. I might not have appealed if I'd known that was the effect it would have. I'd lost everything already. What did it matter if I was in prison or out?'

âIf you're innocent . . .'

âI am.'

âThen you deserve to be free.'

âWill you make the documentary?'

âI don't know if I can.' I hear the panic in my voice and despise myself. Will I be betraying Dad if I do? Betraying something more important if I don't?

âYour father's dead, Fliss. I'm alive.'

I owe her nothing. I don't say it out loud because I shouldn't have to. It should be obvious.

âI'm going back to Angus,' she says quietly. âI can't hide away here for ever, with no one knowing where I am. I need to start living my life again. Angus loves me, whatever's happened between us in the past.'

âDoes he want you back?'

âI think so, and even if he doesn't, he will when I . . .' She leaves the sentence unfinished.

âWhat?' I ask. âWhen you what?'

âWhen I tell him that I'm pregnant,' she says, looking away.

Daily Telegraph,

Saturday 10 October 2009

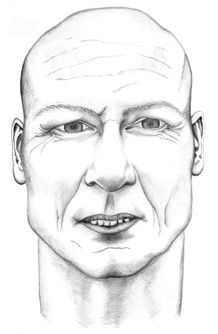

Significant Lead in Helen Yardley Murder

Â

Police investigating the murder of Helen Yardley, the wrongly convicted mother shot dead at her home in Spilling on Monday, confirmed yesterday that they have a lead. The police artist's image below is of a man West Midlands CID are keen to question in connection with a recent attack on Sarah Jaggard, the Wolverhampton hairdresser acquitted of the murder of six-month-old Beatrice Furniss in July 2005. Mrs Jaggard was threatened with a knife in a busy shopping area of Wolverhampton on Monday 28 September. DS Sam Kombothekra of Culver Valley CID said: âWe believe that the same man who attacked Mrs Jaggard may have shot Mrs Yardley. There is evidence that links the two incidents.' Helen Yardley spent nine years in prison for the murders of her two baby sons before having her convictions quashed on appeal in February 2005. A card with 16 numbers on it, reproduced below, was found in her pocket after her death. A similar card was left in Mrs Jaggard's pocket by her assailant.

DS Kombothekra has asked for anyone who recognises the man pictured below to contact him or a member of his team. He said: âWe can guarantee complete confidentiality, so there is no reason to fear coming forward, though we believe this man is dangerous and should not be approached under any circumstances by members of the public. We must find him as a matter of utmost urgency.' DS Kombothekra has also appealed for information about the 16 numbers on the card: âThey must mean something to somebody. If that someone is you, please contact Culver Valley CID.'

Asked to comment on motive, DS Kombothekra said: âBoth Mrs Yardley and Mrs Jaggard were accused of heinous crimes and foundâthough only after a terrible miscarriage of justice in Mrs Yardley's caseâto be not guilty. We have to consider the possibility that the motive is a desire to punish both women based on the mistaken belief that they are guilty.'

12

10/10/09

âI've no idea whether they were the same numbers or sixteen different numbers.' Tamsin Waddington pulled her chair forward and leaned across the small kitchen table that separated her from DC Colin Sellers. He could smell her hair, or whatever sweet substance she'd sprayed it with. Her whole flat smelled of it. He resisted the urge to grab the long ponytail she'd draped over her right shoulder, to see if it felt as silky as it looked. âI don't even know that there were sixteen of them. All I know is, there were some numbers on a card, laid out in rows and columnsâcould have been sixteen, twelve, twenty . . .'

âBut you're certain you saw the card on Mr Nattrass's desk on 2 September,' said Sellers. âThat's very precise, and more than a month ago. How can youâ?'

â2 September's my boyfriend's birthday. I was hanging around in Laurie's office trying to pluck up the courage to ask him if I could leave early.'

âI thought you said he wasn't your boss.' Sellers stifled a sigh. He hated it when attractive women had boyfriends. He genuinely believed he'd do a better job, given the opportunity. Not knowing the boyfriends in question made no difference to the strength of his conviction. Like anyone with a vocation, Sellers felt frustrated whenever he was prevented from doing what he was put on this earth to do.

âHe wasn't my boss as such. I was his researcher.'

âOn the crib death film?'

âThat's right.' She leaned in even closer, trying to read Sellers' notes.

Nosey cow

. If he stuck out his tongue now he could lick her hair. âLaurie never seemed to want to go home, and I was embarrassed to admit that I did,' she said. âEmbarrassed to have made plans that didn't involve defeating injustice, plans Laurie wouldn't have given a toss about. I was hovering round his desk like an idiot, and I saw the card next to his BlackBerry. I asked him about it because it was easier than asking what I really wanted to ask.'

Nosey cow

. If he stuck out his tongue now he could lick her hair. âLaurie never seemed to want to go home, and I was embarrassed to admit that I did,' she said. âEmbarrassed to have made plans that didn't involve defeating injustice, plans Laurie wouldn't have given a toss about. I was hovering round his desk like an idiot, and I saw the card next to his BlackBerry. I asked him about it because it was easier than asking what I really wanted to ask.'

âThis is important, Miss Waddington, so please be as accurate as you can.'

Can I play with your swishy hair while you suck my nads?

âWhat did you say to Mr Nattrass about the card, and what was his response?' For a moment, Sellers imagined he'd asked the wrong question, the X-rated one, but he couldn't have. She didn't look offended, wasn't running from the room.

Can I play with your swishy hair while you suck my nads?

âWhat did you say to Mr Nattrass about the card, and what was his response?' For a moment, Sellers imagined he'd asked the wrong question, the X-rated one, but he couldn't have. She didn't look offended, wasn't running from the room.

âI picked it up. He didn't seem to notice. I said, “What's this?” He grunted at me.'

âGrunted?' This was torture. Couldn't she use more neutral words?

âLaurie grunts all the time â when he knows a response is required, but hasn't heard what you've said. It works with a lot of people, but I'm not easily fobbed off. I waved the card in front of his face and asked him again what it was. Typical Laurie, he blinked at me like a mole emerging into the light after a month underground and said, “What

is

that bloody thing? Did you send it to me? What do those numbers mean?” I told him I had no idea. He snatched the card out of my hand, tore it up, threw the pieces in the air, and turned back to his work.'

is

that bloody thing? Did you send it to me? What do those numbers mean?” I told him I had no idea. He snatched the card out of my hand, tore it up, threw the pieces in the air, and turned back to his work.'

âYou saw him tear it up?'

âInto at least eight pieces, which I picked up and chucked in the bin. Don't know why I bothered â Laurie didn't notice, or thank me, and when I finally got round to asking him if I could leave early he said, “No, you fucking can't.” If I'd known the numbers were important, I'd haveâ' Tamsin broke off, tutted as if annoyed with herself. âI have a vague memory of the first number being a two, but I wouldn't swear to it. I didn't think anything of it until Fliss turned up here in a state last night and told me about the card she'd been sent and an anonymous stalker who might or might not want to kill her.'

Other books

Blood Magic (Dragon Born Alexandria Book 2) by Summers, Ella

Cat's Claw by Susan Wittig Albert

El lector de cadáveres by Antonio Garrido

Ultimate Supernatural Horror Box Set by F. Paul Wilson, Blake Crouch, J. A. Konrath, Jeff Strand, Scott Nicholson, Iain Rob Wright, Jordan Crouch, Jack Kilborn

Ravensong by ML Hamilton

Intimate Exposure by Portia Da Costa

Once Upon a Dream by Liz Braswell

El milagro más grande del mundo by Og Mandino

Locke and Load by Donna Michaels

Blast From the Past by Ben Elton