The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment (36 page)

Read The Crash Course: The Unsustainable Future of Our Economy, Energy, and Environment Online

Authors: Chris Martenson

Tags: #General, #Economic Conditions, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Development, #Forecasting, #Sustainable Development, #Economic Development, #Economic Forecasting - United States, #United States, #Sustainable Development - United States, #Economic Forecasting, #United States - Economic Conditions - 2009

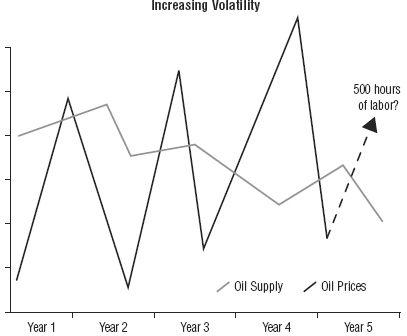

But even as economic activity slowly trips down a stairwell, oil prices are doing the exact opposite, as seen in

Figure 25.2

. Oil prices make a series of “higher highs” on each leg of the cycle (as well as “higher lows”). The swings in the price of oil also grow larger and more volatile as time progresses, further inhibiting additional investment by oil companies, which cannot trust their ability to model and manage cash flows against investment returns. The safest bet is to hoard cash, hoping for smoother sailing in the future. The ultimate price for oil is far higher than most people can imagine, but its intrinsic value—350 to 500 hours of human labor per gallon—ultimately supports these much higher prices. The most magical of natural resources is no longer taken for granted.

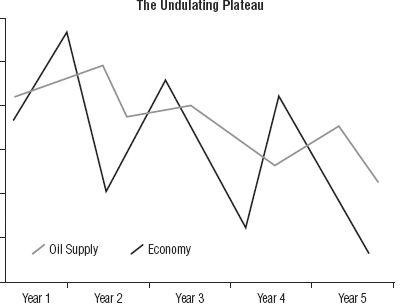

At every turn of the cycle on the undulating plateau, social and economic complexity shrinks. Adjustments are made to the new reality of less energy, which for many brings an unpleasant and unwelcome period of transition. Thousands of job classifications, mainly service-oriented and not directly connected to the production of secondary wealth, are no longer relevant and disappear. Patterns of living re-form around the new reality of less energy and a greatly simplified economy. People find ways to live closer to work and food, adjust to having less mobility than in the past, and retrain or “reskill” themselves in order to find income-producing work.

The good news is that the undulating plateau offers people and nations the luxury of time to mentally, emotionally, physically, and financially adapt to the unavoidable new reality. No major financial disasters or wars break out, allowing critical resources to be marshaled and appropriately directed.

Prepare to Be Surprised

The biggest surprise to me would be if the future actually resembled any of the scenarios I just described. I’m both prepared and expecting to be surprised. The basic rule about complex systems is that they’re inherently unpredictable, at least with respect to the precise details of exactly what, when, and how much will transpire.

However, the larger model, in which a complex system will become simpler if starved for energy, is a known quantity. Imagine that our economy is a snow globe. As long as it continues to be shaken vigorously, the flakes will remain in a suspended state of complexity. Cease the input of energy (the shaking), and the flakes will settle and assume a much less complex state of existence, no longer bumping into hundreds of their neighbors in interesting and unique configurations. We may not be able to predict exactly how, where, and when all the flakes will settle, but we know that they will.

I’m not at all sure how a massive, complex global economy predicated on exponential growth will change when net energy declines. But here are my best guesses:

1.

Tertiary wealth in all of its many forms, but especially those whose major value derives from the assumption of future growth, will decline in value and prominence. Said simply, we face decades of sub-par (at best) to catastrophic (at worst) returns in stocks and bonds. Pensions and 401(k)s will fail to deliver the future that many have been counting on. Paper wealth will lose value to the degree that it bore unrealistic assumptions about growth at its core, as well as the degree to which it is overcreated by governments and central banks during the transitionary period.2.

The recent great trends in manufacturing and globalization will reverse; the pendulum will swing the other way. Economies that had previously shifted to become 80 percent service-oriented will need to shift back to being more manufacturing- and production-oriented. Where products were shipped and reshipped in various states of assembly to the lowest-cost production centers regardless of their global location, supply chains will have to be significantly shortened and production relocalized.3.

The proportion of personal income devoted to food and energy, which reached all-time lows in the late 2000s, will steadily increase. This will leave correspondingly less income for other discretionary expenditures.4.

Monetary magic—the application of stimulus and thin-air money—will be tried and tried again, but in the absence of increases in net energy, it will fail to work as intended. The more these responses are attempted, the higher the likelihood of a destructive collapse in the currency or currencies involved. The United States is especially at risk, given that trillions of its dollars are housed offshore, which means that they could be redeemed at any time on the whim of their holders.5.

The U.S. government has a future date with a fiscal crisis and will have to trim its expenditures (possibly by as much as 50 percent) and increase taxes enormously (by perhaps 100 percent) to deal with the fact that it is fundamentally insolvent. The chance of this fiscal crisis morphing into a currency crisis is exceedingly high. Retirement dreams will have to be deferred by tens of millions, if not abandoned.6.

Similar difficulties to the United States will be faced by other overly indebted countries facing their own entitlement difficulties, including Japan, Greece, Ireland, Spain, the United Kingdom, and France.

You’ll note that the scenarios I put forth are relatively benign: I propose no wars, no social unrest, no political upheavals, or anything else of that stressful nature. However, historically, the number one cause of wars has been resource conflicts. Given that we’re about to enter one of the most significant resource shortages in the history of a world that is more well-armed than ever before, it will take a rare combination of events and diplomacy to avoid heading to war over the remaining resources.

I maintain hope that we can avoid such an outcome, but this hope rests upon enough people, especially those in power, understanding the actual source of our predicament, choosing prosperity over growth, and using our remaining surplus to build rather than destroy.

Stay Alert

Because we can only glimpse the broad outlines of what is likely to happen, not the details or the timing, it’s important to remain alert. I like to think of myself as being an “information scout” for my clients, and I’m constantly sifting through every facet of information that develops in politics, geopolitics, and, of course, any of the three Es. It’s all potentially important. I wish I could extract a few thousand words of simple advice that would work for every person and any company, but this is neither possible nor feasible.

- Invest defensively.

- Build resilience into your physical systems and financial dealings.

- Favor liquidity and safety over the potential for higher returns.

- Mentally prepare yourself for a very different future.

- Practice doing more with less.

But the details are endless and specific.

The information in this book has hopefully prompted you to consider that there’s some value in becoming better prepared, whatever “prepared” means in your individual context. At my web site (

www.ChrisMartenson.com

), you will find a free “What Should I Do?” series that will walk you through the basic steps. After you’ve taken some initial steps, you might wish to join the rich and vibrant community of intelligent people who have assembled there, each of whom is working through the specifics of responding in their own ways. I’ve created a place for people to connect around these ideas that is safe, inviting, mature, and rational. In other words, it’s a rare place where one can have a civil, thoughtful discussion about these topics on the Internet.

In the next few chapters, you will find more answers to the question of what you should do. And I hope you will consider joining us online at

www.ChrisMartenson.com

to explore these issues further.

PART VII

What Should I Do?

CHAPTER 26

The Good News

We Already Have Everything We Need

As daunting as the challenges and predicaments outlined in this book may seem, the good news is that we already have everything we need to create a better future. All of the understanding, resources, technology, ideas, systems, institutions, and thinking are already available, invented, or in place, ready to be deployed in service of a better future; we just need to decide to make use of them. By simply reorienting our priorities, we can simultaneously buy ourselves time and assure that we choose prosperity over growth.

Fundamentally, this book and my work are about exposing the choices and options we have. As dire as things may seem, the future has not yet happened. Hope remains that we can respond intelligently to the current predicaments, and even create something better for ourselves along the way.

Yet it’s also true that the stadium is rapidly filling with water and our choices matter very much from here on out. There’s a lot less room for error than there was a few decades back, when we had plenty of time to make mistakes and fumble around with our handcuffs. But now that the water is swirling up the bleacher stairs, our choices take on new urgency and matter a great deal. There’s no time to waste making wrong choices anymore. History is sitting up straight with pencil poised over notebook, carefully watching to see what we do next and determine how our efforts should be remembered.

Technology

We don’t need to develop any new technologies, although it will be nice when they come along. We already know how to build highly efficient machines and dwellings that use tiny fractions of the energy of those currently in use. We can live extremely comfortable lives using much less energy than we currently consume by making a few small changes in our technology choices and daily routines. By doing so, we will preserve some energy for the future, which will allow us the gift of time. There’s nothing to prevent us from making such a change, except possibly a lack of a coherent vision from our leadership that this is an important thing to do.

It will be fantastic when higher-capacity batteries are developed, but we don’t need them in order to immediately begin using existing technology to consume less electricity. For example, electricity is still consumed to heat water for home and commercial use, yet solar hot water panels are a proven, decades-old technology that works and is economically sound even at current energy prices. Despite this, such panels are relatively rare in some countries, the United States included. Using fossil fuels to heat water when the sun can do it efficiently and reliably is a mistake, especially when simple technology already exists that can be installed quickly and which will save money and energy over time. Eventually we will collectively come to that conclusion, but why wait? What is stopping us from making the installation of solar hot water panels a top priority and beginning immediately? The limitations that do exist have nothing to do with technology; they are social and political in nature.

For example, we still beam an enormous amount of electricity into outer space in the form of stray photons from the area lights that we use in every city and along major roadways. These could (and should) be replaced with LED technology that uses a fraction of the electricity of halide and halogen lamps. Nothing prevents us from doing this today, other than inertia and a lack of urgency that it needs to be done.

We already know how to build houses that face the sun and use almost no energy, we know how to build smaller and more fuel-efficient vehicles, we know how to live, work, and play near where we live, and we have all the technology we need to live far more sustainably than we currently do. So what is holding us back? I submit that there’s nothing rational or logical or even economically sensible about our lack of action on these matters; the cause lies elsewhere.

Food

We know that healthy soils produce more and better food than ruined, nearly biologically sterilized dirt. Reason tells us that flushing vital and irreplaceable nutrients into the sea isn’t a good idea. Eventually we’re going to have to find some way of recycling nutrients back to the farms on which our food grows. We understand how to optimize yields for a given area based on the types of soils and the rainfall that exists there. We already know that growing some crops in arid regions is an energetic and biological mistake.

We don’t need any more studies, additional insights, or new books to be written. We already know all of these things, and many more besides. We don’t need a deeper understanding of what we need to do—we already have the necessary understanding. What we do need is the desire to make such changes a priority and to choose the sustainable path.

Food needs to be grown and consumed locally, and strategies for recycling the nutrients back to the farms need to be implemented. You can help start this process by demanding local foods, which is easy—just start buying them. By supporting local farmers, you help to secure the food that you and your community need in both the short term and the long term. Even better, start growing your own food in a garden, a window box, or even just a pot on the porch. Solutions to the issue of food, though daunting in scale, are easy to conceptualize and are already underway to some extent in virtually every community.

Energy

The prescription here is simple:

We need to be as careful and conservative in our use of energy as we can possibly be

. This means

stop wasting energy

. Not stop

using

energy; stop

wasting

it. That is a good first step. Given that fossil fuels are a “one and done” arrangement, sliding as they do down the frictionless entropy slide on their way to becoming lazy heat, we need to develop and nurture a brand-new appreciation for just how valuable energy really is. We really ought to see our fossil energy sources as the one-time, irreplaceable master resources that they are.

Currently, fossil energy sources are “valued” by an abstraction called money, which does an incredibly good job of masking their true worth by concealing the fact that they are limited and depleting. The idea that gasoline, a nonrenewable resource, is only considered to be “worth” a few dollars a gallon, when it capably performs the same amount of work as a human laboring for hundreds of hours, is just silly. Clearly it is worth more to us than its price would indicate. It should be valued more highly, and if it were, I’m confident that it would be used more wisely. If we want to preserve the order and complexity of our economy, and, by extension, of our society, then we need to begin by better appreciating the role of energy in delivering and maintaining both order and complexity.

It is this connection between the economy and energy that’s entirely missing from the current practice of mainstream economics. It’s almost as if the current practitioners of economic theory (with relatively few exceptions)

1

are entirely unaware that the economy would have no form, no function, and no “life” without energy. This intellectual disconnect explains why we’re so deeply mired in the predicaments in which we find ourselves, and it explains why I view the risks to our future so seriously.

As Max Planck, the famous physicist, once said, “A new scientific truth does not triumph by convincing its opponents and making them see the light, but rather because its opponents eventually die, and a new generation grows up that is familiar with it.”

2

In other words, science advances one funeral at a time. Historically, new ideas do tend to run into stiff opposition from the establishment. There are too many economists and other people in positions of power who seem to have no idea of the connections between the economy, energy, and the environment. When reality finally convinces enough of them that it needs to be taken seriously, in what sort of a world will we be living?

Luckily, we don’t have to wait for economists to arrive at the truth before we begin to act more rationally and use our fossil fuels as if they were an extremely valuable, nonrenewable, one-time inheritance.

Economy and Money

We can already tell that our debt-based, backed-by-nothing fiat currency is performing badly, and as its resource props are pulled away, it’s likely to perform even more poorly in the future and eventually wobble and fall. To counter this, we will need new forms of money, possibly several, that can operate tolerably well in a world without growth, along with people to manage them. Fortunately, several new forms of money already exist, including mutual credit arrangements (such as LET systems),

3

demurrage money,

4

and various forms of money that are backed by something tangible. If we were to put more of these kinds of currency into play alongside our current form of money, then we would have a more resilient ecosystem of money, where if one form gets into difficulty of some sort, there are others waiting to pick up the slack. If a single currency is like a concrete channel designed to carry the maximum amount of water, multiple currencies are like wetlands designed to maximize the buffering of the water levels in times of both drought and flood.

The very first step, however, needs to begin with the idea that you cannot possibly borrow more than you earn forever. The implication of this is that the U.S. government will need to cut spending to bring it in line with the actual economic realities that will result from “too much debt” and a looming resource predicament. The entire U.S. society needs to “deleverage”—a fancy word for “cut debt”—and begin to live more carefully within its true earning potential. We already know this; there are dozens of well-constructed models, books, and research papers showing that current spending is unsustainable. But it bears reminding—and begs for action.

Population

We cannot beat around the bush on this “third-rail” topic any longer: We need to stabilize world population at a level that can be sustained. If we don’t, then nature will do it for us, and not pleasantly, either. This means stabilizing world population in perpetuity, not only for a little while longer. We may not know what this stable level is just yet, and more study is certainly needed, especially in light of declining energy resources. But we should do everything we can to avoid badly overshooting the number of humans that can be sustainably supported on our planet while carelessly avoiding an examination of the role of petroleum in supporting those populations.

According to the work of professor William Rees, humans are operating well past the Earth’s sustainable carrying capacity, which is a function of two things: the number of humans on the earth and their standards of living.

5

According to this work, every organism has an ecological footprint, and humans now require the equivalent of 1.4 Earths to sustain themselves. There are only two ways to solve this problem: reduce the number of people or lower living standards. If those are our options, would we prefer to have fewer people in the world enjoying elevated standards of living, or more people in the world with reduced standards of living? In other words, would we prefer prosperity or growth? Saying “both” is the same thing as saying “growth,” because in the battle between growth and prosperity, growth always wins.

Kicking and Screaming

What we need more than anything is to reshape the stories that we tell ourselves. Right now the “growth is essential” story is firmly lodged in our national and global narratives, and so that’s what we get—policies and actions that chase growth. If instead we shared a story that placed “long-term prosperity” as our highest goal, then we would hopefully get different actions and results.

But waiting for politicians to arrive at this new story on their own isn’t a compelling strategy. As we look back across the long sweep of history and note when the status quo was challenged and changed, we would find that such change was never intended by those in the center to radiate outward. Every single social gain of note—labor rights, civil rights, women’s rights, the environmental movement, or any other that you care to think of—began on the periphery of society and was brought, kicking and screaming, to the center.

If it seems as though I’m suggesting that a social movement is needed, it’s because I am. The story that I have told in this book needs to be spread far and wide. Others need to tell it in their own way, because we will need many teachers to get the message into every corner and down every side street. We need a tipping point of awareness about the true nature of the predicaments we face.

We each need to be responsible for helping to change the story so that we can have a better future. The alternatives are unacceptable.

The Good News . . .

Again, we don’t need anything that we don’t already have in order to turn this story around. We know what the issues are, and we know what we have to do. Now we need to make those things a priority.