The Cutting Season

Read The Cutting Season Online

Authors: Attica Locke

| The Cutting Season | |

| Locke, Attica | |

| Harper (2012) | |

| Rating: | ★★★☆☆ |

In

Black Water Rising

, Attica Locke delivered one of the most stunning and sure-handed fiction debuts in recent memory, garnering effusive critical praise, several award nominations, and passionate reader response. Now Locke returns with T

he Cutting Season

, a riveting thriller that intertwines two murders separated across more than a century.

Caren Gray manages Belle Vie, a sprawling antebellum plantation that sits between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, where the past and the present coexist uneasily. The estate's owners have turned the place into an eerie tourist attraction, complete with full-dress re-enactments and carefully restored slave quarters. Outside the gates, a corporation with ambitious plans has been busy snapping up land from struggling families who have been growing sugar cane for generations, and now replacing local employees with illegal laborers. Tensions mount when the body of a female migrant worker is found in a shallow grave on the edge of the property, her throat cut clean.

As the investigation gets under way, the list of suspects grows. But when fresh evidence comes to light and the sheriff's department zeros in on a person of interest, Caren has a bad feeling that the police are chasing the wrong leads. Putting herself at risk, she ventures into dangerous territory as she unearths startling new facts about a very old mystery—the long-ago disappearance of a former slave—that has unsettling ties to the current murder. In pursuit of the truth about Belle Vie's history and her own, Caren discovers secrets about both cases—ones that an increasingly desperate killer will stop at nothing to keep buried.

Taut, hauntingly resonant, and beautifully written,

The Cutting Season

is at once a thoughtful meditation on how America reckons its past with its future, and a high-octane page-turner that unfolds with tremendous skill and vision. With her rare gift for depicting human nature in all its complexities, Attica Locke demonstrates once again that she is "destined for literary stardom" (

Dallas Morning News

).

Attica Lockeis a screenwriter who has worked in both film and television. A native of Houston, Texas, she lives in Los Angeles with her husband and daughter.

The Cutting Season

A Novel

Attica Locke

Dennis Lehane Books

A Haunting Discover

y

Ascension Parish, 2009

I

t was during the Thompson-Delacroix wedding, Caren’s first week on the job, that a cottonmouth, measuring the length of a Cadillac, fell some twenty feet from a live oak on the front lawn, landing like a coil of rope in the lap of the bride’s future mother-in-law. It only briefly stopped the ceremony, this being Louisiana after all. Within minutes, an off-duty sheriff’s deputy on the groom’s side found a 12-gauge in the groundskeeper’s shed and shot the thing dead, and after, one of the cater-waiters was kind enough to hose down the grass. The bride and groom moved on to their vows, staying on schedule for a planned kiss at sunset, the mighty Mississippi blowing a breeze through the line of stately, hundred-year-old trees. The uninvited guest certainly made for lively dinner conversation at the reception in the main hall. By the time the servers made their fourth round with bottles of imported champagne, several men, including prim little Father Haliwell, were lining up to have their pictures taken with the viper, before somebody from parish services finally came to haul the carcass away.

Still, she took it as a sign.

A reminder, really, that Belle Vie, its beauty, was not to be trusted.

That beneath its loamy topsoil, the manicured grounds and gardens, two centuries of breathtaking wealth and spectacle, lay a land both black and bitter, soft to the touch, but pressing in its power. She should have known that one day it would spit out what it no longer had use for, the secrets it would no longer keep.

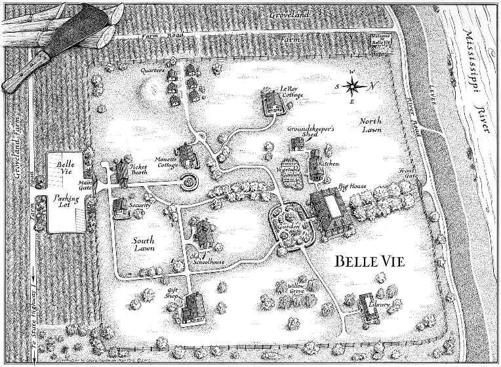

The plantation proper sat on eighteen acres, bordered to the north by the river, and to the east by the raw, unincorporated landscape of Ascension Parish. To walk it—from the library in the northwest corner to the gift shop and then over to the main house, past the stone kitchen and the rose garden, the cottages Manette and Le Roy, the old schoolhouse and the quarters—took nearly an hour. Caren had learned to start her days early, while it was quiet, heading out before sunlight—having arranged for Letty to arrive by six a.m. at least three days a week, while Caren’s daughter was still sleeping. Six mornings out of seven, she made a full sweep of the property, combing every square inch, noting any scuffed floors or dry flower beds or drapes that needed to be steamed—even one time changing the motor in one of the gallery’s ceiling fans herself.

She didn’t mind the work.

Belle Vie was her job, and she was nothing if not professional.

Though she could in no way have prepared herself for the grisly sight before her now.

To the south and west, across a nearly five-foot-high fence, where Caren was standing, the back five hundred acres of the Clancy family’s 157-year-old property had been leased for cane farming since before she was born. Over the fence line, puffs of gray smoke shot up out of the fields. The machines were out in the cane this morning, already on the clock. The mechanical cutters were big and wide as tractor trucks, fat, gassy beasts whose engines often disturbed the natural habitat, chasing rats and snakes and rabbits from their nests in the cane fields—and come harvest time each year, the animals invariably sought out a safe and peaceful living on the grounds of Belle Vie. Luis had run them out of the garden, cleared their fecal waste from his toolshed, and, on more than one occasion, trapped and bagged a specimen to take home for God knows what purpose. And now some critter had dug up the dirt and grass along the plantation’s fence line and come up with this.

The body was face down.

In a makeshift grave so shallow that its walls hugged the corpse as snugly as a shell, as if the dead woman at Caren’s feet were on the verge of hatching, of emerging from her confinement to start this life over again. She was coated with mud, top to bottom, her arms and legs tucked beneath her body, the spine in a curved position. The word

fetal

came to mind. Caren thought, for a brief, dizzying second, that she might faint. “Don’t touch her,” she said. “Don’t touch a thing.”

S

he’d been up since dawn, that cold Thursday morning.

It was a day that had already gotten off to a wrong start, before she’d even stepped foot out of the house . . . though for an entirely different reason. She’d woken up that morning to a message on her cell phone, one that had set off a minor staff crisis. Donovan Isaacs had had the nerve to call in sick for the third time in two weeks, this time leaving a nearly incoherent voice-mail message on her phone at four o’clock in the morning, and keeping Caren in her pajamas for over an hour as she sent e-mails and placed phone calls, searching for a replacement. She didn’t know if it was because she was a woman or black—a

sister

, as he would say—but she’d never had an employee make so little effort to impress her. He was chronically late and impossible to get on the phone, responding sporadically to text messages or nagging calls to his grandmother, with whom he lived while taking classes at the River Valley Community College and working here part-time. His salary, like those of the other Belle Vie Players, was paid by a yearly stipend from the state’s Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism, which made firing him a bureaucratic headache, but one she was no less committed to pursuing. But that was later, of course. Right now she needed a stand-in for the part of FIELD SLAVE #1. She was about a heartbeat away from making a call to the theater department at Donaldsonville High School, willing to settle for a warm body, at least, when finally, at a quarter to seven, Ennis Mabry returned one of her messages, saying he had a nephew who could take over Ennis’s role as Monsieur Duquesne’s trusty DRIVER, and Ennis could step in to play Donovan’s part, which, he assured her, he knew by heart.

“Don’t worry, Miss C,” he said. “The kids’ll have they show.”

L

etty was on the kitchen phone when Caren came downstairs a few minutes later. She was standing over the stove, talking to her eldest daughter, a girl Caren had met only once, on a day when Letty’s ’92 Ford Aerostar wouldn’t start and Gabriela had to drive all the way from Vacherie to come pick her up. She was a good kid, Letty reported at least once a week. She was on the honor roll, had held a job since she was fifteen, and didn’t mess around with boys. And three days a week, Gabby made a hot breakfast for her younger brother and sister, packed their lunches, and drove them to school, all so her mother could come to work before dawn and do the very same for Caren’s child. At the stove, Letty was hunched over a pot of Malt-O-Meal, talking about Gabby’s little brother and speaking Spanish in a coarse whisper, only a few words of which Caren could make out at a distance:

thermometer

and

aspirin

and some bit about

hot tea

.

Caren had two school tours scheduled before lunch and a cocktail reception in the main house that evening, the menu for which had yet to be finalized. She couldn’t do this day without Letty or her rusty van or the Herrera kids up and well enough for school. They were all tied together that way. Caren’s life, her job, depended on Letty being able to do hers. She gave Letty’s shoulder a warm squeeze before walking out, mouthing the words

thank you

and mentally making a list of all the creative ways she might make it up to her, knowing, in her heart, that any such token is worthless when your kid is sick. It was not something she was proud of, skipping out like that. But very little in Caren’s life, at that point, was. Pride, as a method of categorizing one’s personal life and history, was something she’d long given up on. There was her daughter, and there was this job.

The air outside was cold for October, and wet, still drunk from a late-night rain that had soaked Belle Vie, and again she thought it was wise to warn the evening’s host against outdoor seating. Still, she would need Luis to pull at least one of the heat lamps from the supply closet in the main house. A number of Belle Vie’s paying guests liked to take an after-dinner brandy on the gallery, to say nothing of the smokers who routinely gathered there. The plantation had finally gone smoke-free the year before—in the main house, at least, and the guest cottages. Caren’s living quarters, a two-bedroom apartment on the second floor of the former

garçonnière

and overseer’s residence—which also housed the plantation’s historical records—still carried a heavy scent of burnt pipe tobacco, a faintly sweet aroma she had come to think of as home.

She had, for better or for worse, made a life here.

She had finally accepted that Belle Vie was where she belonged.

Her work boots, a weathered pair of brown ropers, were waiting where they always were, just outside the library’s front door. She slipped them over her wool socks, zipping a down jacket and pulling a frayed

TULANE SCHOOL OF LAW

cap from the pocket. She slid the hat over her uncombed curls, feeling their thick weight against the back of her neck. On her right hip, she carried a black walkie-talkie. On her left, a ring of brass keys rode on her belt loop, bumping and jangling against the flesh of her thigh as she started for the main gate. She’d cover more ground in less time if she borrowed the golf cart from security. The plan was to drive along the perimeter first, then double back, park by the guest cottages, and walk the quarters on foot. She was always careful not to leave tire tracks in the slave village. She was responsible for even this detail.

It’s not that Belle Vie wasn’t well staffed.

There was a cleaning crew that came several times a week, more if there were guests in the cottages or events scheduled back-to-back on weekends. And Luis, who had been on the payroll since 1966—when the Clancy family fully restored the plantation that had been in their family for generations—could probably run the place himself if he had to. Still, she was surprised by the little things that got overlooked. She once found a used condom on the dirt floor of one of the slave cottages. Drunken wedding guests, she had learned, were by far the horniest, most unscrupulous people on the planet: neither a sense of the macabre nor common decency would stop them once they got their minds set on something, or someone. And Caren didn’t think any third-grader’s first school field trip ought to include a messy, impromptu lesson about the mating habits of loose bridesmaids.

From high overhead, sunlight studded the green grass with bits of coral and gold, as she rode along beneath a canopy of aged magnolias that shaded the main, brick-laid road through the plantation; their branches were deep black and slick with lingering rainwater. Mornings like this, she didn’t try to fight the romance of the place. It was no use anyway. The land was simply breathtaking, lush and pure. She drove past the gift shop, then north toward Belle Vie’s award-winning rose garden, which sat embedded within a circular drive just a few feet from the main house. The nearly two-hundred-year-old manse was held up by white columns, and adorned with black shutters and a wrought-iron balcony that overlooked the river to the north and the garden to the south. Luis and his one-man maintenance crew had done a grand job with

le jardin

, coaxing rows of plum-colored tea roses and hydrangeas into an unlikely fall showing. Mrs. Leland James Clancy, had she lived, would have been most proud.

All along the drive, Caren made mental notes.

The hedges in front of the guest cottages could stand a trim. And whatever the latest fertilizer formula or concoction Luis had sprinkled on the hill behind the quarters, it wasn’t working. There was still a narrow patch of earth out that way—grown over the foundation of some building long forgotten and not appearing on any plantation map—that remained as stubbornly dull and dry as it had even when Caren was a kid, no matter what Luis tried. Food scraps and horse shit, or cold, salted water.

Down by the quarters, grass simply refused to grow.

Caren was, at that moment, a mere thirty yards or so from a crime scene, but, of course, she didn’t know it yet. She saw only the break in the land, where the earth had been disturbed. But from afar, it looked like a rabbit or a mole or some such creature had been digging up the ground along the fence line that separated the plantation from the cane fields—another problem, she thought, since the Groveland Corporation took over the lease on the “back five.” Ed Renfrew, when his family farmed the land, always made a point to monitor his side of the fence. If a critter tore up the dirt or left any such blot on the landscape, he’d always tend to it right away. But Hunt Abrams, the project manager for the Groveland farm, had never uttered more than ten words to Caren, had never gone out of his way to acknowledge her existence. She lifted the walkie-talkie from the waistband of her jeans, using it to alert Luis to the problem, telling him to get somebody out there to clean up the mess. “Sure thing, ma’am,” he said.

Later, two cops would ask, more than once, how it was she didn’t see her.

She could have offered up any number of theories: the dirt and mud on the woman’s back, the distance of twenty or thirty yards between the fence and Caren’s perch behind the driver’s seat, even her own layman’s assessment that the brain can’t possibly process what it has no precedent for. But none of the words came.

I don’t know

, she said.

She watched one of the cops write this down.

B

ut it was the quarters, wasn’t it?

The reason she had missed that girl, the dirt and the blood.