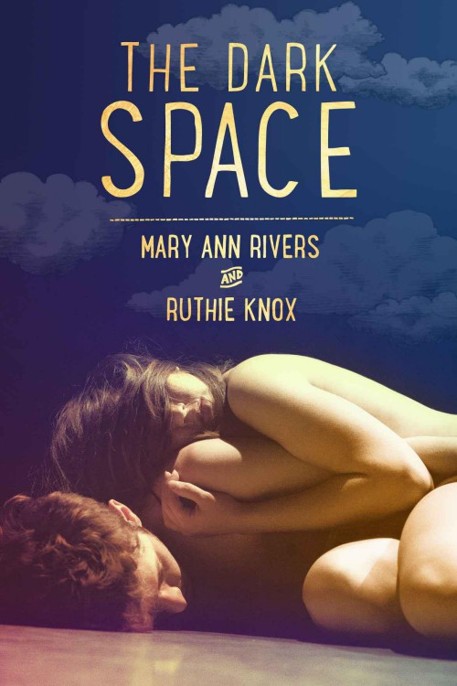

The Dark Space

Authors: Mary Ann Rivers,Ruthie Knox

The Dark Space

is a work of fiction. Names, places, and incidents either are products of the authors’ imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2015 by Ruth Homrighaus and Mary Ann Hudson. All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Brain Mill Press.

www.brainmillpress.com

ISBN 978-1-942083-00-9

eBook ISBN 978-1-942083-01-6

Cover photograph © Jishnu Guha.

Cover design and original text illustrations by Book Beautiful.

Interior design by Williams Writing, Editing & Design.

Interested in reading more from Brain Mill Press? Join our mailing list at

www.brainmillpress.com

.

Cal

It is impossible that you will believe everything in this story, even though all of it is true.

Even though all of it means that right now, I am smiling up at her while she smiles down at me, her face incandescent. This is the only word I can even think of, looking at her, feeling her —

incandescent

.

I’m gripping her hips while she takes me inside of her, and she is glowing. I think I’m glowing, too.

I wonder if the light we’re making will show up in the pictures our friend Sarah is taking. The shutter is snapping and whirring, and I hope so. I hope everyone in the whole world will look at these pictures and see everything. I hope I will look at these pictures fifty years from now and think,

We were like a thousand fucking candles together.

Her laugh tastes like it always does. Her skin.

Winnie

I didn’t plan to sign up for the class.

I was an economics major, which is practical, but I also wanted to be Phi Beta Kappa, so even though the college I went to has no core curriculum, I had to take a few credits in every area — humanities, social sciences, science, and the arts.

I didn’t

plan

to sign up for the class, but I needed eight credits in the arts, and I took the prerequisite my second year. You can’t get in to Contact Improv unless you’ve taken the prerequisite. So I did. But I didn’t plan to take the class.

Not exactly. I just sidled my advisor around to suggesting it.

Recommending

it, even.

“Because you seemed to enjoy that theater class,” he said.

“Because you might benefit from greater ease in social situations,” he suggested.

“Because it helps sometimes, in life, to learn to pretend you feel something different from what you’re really feeling.”

This last, I’m sure, because I look like a small and terrified mouse. And I mean that not in the adorable way —

Oh, I have mousy brown hair and precious tiny hands!

— but truly. My rodenty face, my pale blinking eyes, my flat short hair and skin the blue of skim milk. They unsettle people.

I’d spent my whole life learning how not to unsettle people, until I became the sort of person who’s barely visible at all. That girl who sits on the mid-back-left side of your classroom, whose name you don’t know. The student at the coffee shop who you know you’ve served before, lots of times, even though you never remember her order.

I didn’t plan to take Contact Improv, because from the first moment I read the course description in the online catalog, the very notion of such a class unsettled

me

.

When I looked around at the people trickling into the auditorium, sitting in the theater’s seats as far away from each other as possible, I thought,

I have known these people my whole fucking life.

That’s what happens when you’re a professor’s kid — your whole circadian rhythm is juiced by the academic calendar. As a matter of fact, you realize, at some horrifying point, that you were fucking conceived and born on school breaks. Count back from my spring break birthday, and there’s my parents, partying over the three-day Fourth of July weekend.

My daycare was the space under my dad’s keyhole desk, in his basement office.

The first nipple under my shaking, underage palm belonged to a dark-eyed undergraduate. When she asked,

You really go here?

I could truthfully answer, even as my high school trig homework burned a hole in my Jansport,

Yeah, I’ve been going here forever.

I’ve been waiting to graduate, literally, since I can fucking

remember

. ’Cause that’s the deal, it’s always been the deal, I can do whatever it is I want, no pushback, as long as I “take advantage” of the free college education offered to faculty’s kids.

Fine.

One more semester, the most worthless piece of paper I can think of is in my back pocket, and Los Angeles is a road trip away. All the sun and aimlessness I can possibly muster will burn away the nine-month calendar in my brain like it was one of those forty-pound disfiguring tumors.

I’ll be free.

I’ll make movies, I’ll learn to surf, I’ll untie bikinis, I’ll work at a diner, I’ll share a shitty apartment with five other aimless dudes, I’ll wake up stoned on a beach at five in the morning, I’ll sell celebrity home maps, I’ll have to hock my car and take the bus and get my bike stolen ten times.

That’s what I was thinking when I looked at everyone on the first day of Contact Improv.

That, and the fact that I would probably make out with, grope, cuddle, smell, and taste every single one of them before the class was finished in the spring.

That guy, with the hipster chops — I was gonna feel those all over my face. That red-headed girl — I fucking hoped that girl was in the class and not just talking to a friend — I’d have signed up twice to practice stage kissing with her. The dude who recorded synth in his dorm all the time, the girl who had a sleeve of a pin-up zombie, the one who had folded herself in half in her theater seat, her knees under her pointy chin, her short hair sticking up in back like she slept on it.

Might as well

, I thought, when I clicked on and added the course to my registration cart.

I’ll kiss ’em all goodbye.

Here is what I knew about kissing before Contact Improv: nothing.

A kind of nothing.

Because there are different kinds of nothing — a fact that no one ever tells you. There are different ways to be weightless, a dozen methods of entering a room invisibly, a hundred strategies for never drawing attention to yourself.

I am an expert in nothing. If I had written my senior thesis on nothing, instead of the economics of microcredit, I would have noted, first, that nothing has texture and heft.

Nothing has the nap of a discarded velveteen couch. It’s soft as a kitten in one direction, but when you pet it the other way it releases the musty smell of storage, and it feels stiff and unpleasant against your hand.

What I knew about kissing was that you put your mouth against another person’s mouth, and something happened.

You breathed through your nose and pushed your tongues around. Somehow you knew how much to push, and when, and how to keep spit from draining down your chin. Or you kissed like in the movies, clutching each other’s faces while the camera spinning around you mirrored the spinning in your heart, the dizzy-light wonder of feeling wanted.

All of this I learned from books and movies, magazines and Internet clips. But what I knew about kissing before Contact Improv was nothing.

The advantage of nothingness and expert invisibility is that I can

learn

, and I can

see

.

That first day, sitting on the stage in what Maggie called our “share circle,” a term I rolled my eyes at —

then

— I saw five males, five females, plus me.

What I learned from this observation is that there was something about this class that held some incentive for males. The male-to-female ratio of Contact Improv was nearly equal, and this was rarely the case on our small liberal arts campus.

Small liberal arts campuses are for women and men who somehow believe they are exceptions to the dominant culture. But of course are not.

What I saw was that the males were on one side of the share circle, and the females were on the other.

What I learned was that this meant that everyone’s insouciant posture and witty introductions meant nothing.

Nothing.

Maybe most of them would have known, if I had asked them, how to kiss, but they did not know —

then

— if what they really wanted to do was kiss each other. For credit.

What I saw, when I said my name to the group,

Winnie Frederickson

, was Maggie’s large blue eyes connect with mine for a longer-than-normal time, and before she looked away she looked at me again, looked at my entire body sitting on the floor of the stage.

What I learned was that I would not be permitted to be invisible.

My expertise at nothingness would not help me here.

This professor, who introduced herself as “Maggie,” who was very obviously not wearing a bra under her leotard and whose feet were bare at the hems of her sweatpants, saw me.

That meant everyone else saw me, too.

I learned this when Cal, the Classics professor’s kid, nudged my thigh with his knee and whispered, “Maybe teacher’s found her pet. Whatcha think?”

Then I saw his blush when I looked right back at him, fully something, fully weighted by the gravity of the stage floor, fully visible, and said — did not whisper — “I think this time, it’s not you.”

I don’t know what he saw.

Cal

I’m a guy with a limited set of appeals. I’m short as fuck, skinny like a heroin junkie, and more than one girl has told me I get annoying after about a week.

I make it work, though, because I know what my appeals are.

That’s what I’d tell anybody who complained to me that he couldn’t get laid at our college —

Dude, you’re doing it wrong.