The Darling Dahlias and the Confederate Rose (28 page)

Read The Darling Dahlias and the Confederate Rose Online

Authors: Susan Wittig Albert

“I never count my chickens before they’re hatched,” Verna muttered. “I’ll believe this when it happens.

If

it happens.”

“When what happens?” Ophelia asked, coming to the table with a pitcher of lemonade.

“Nothing,” Verna said hastily, and held up her glass. “Are you offering refills on that lemonade?”

“Gif me a vhisky,” Myra May said huskily. “Ginger ale on the side, and don’t be stingy, baby.”

“Congratulations on your new job, Opie,” Lizzy said warmly, as Ophelia filled the glasses. “Charlie Dickens says you’re a whiz on that Linotype machine.”

“New job?” Bessie slid onto the seat next to Lizzy. “Ophelia has a job?”

“At the

Dispatch

,” Ophelia said proudly. “Mr. Haydon is teaching me the Linotype machine. And Mr. Dickens says that if things work out, maybe I can take a crack at being advertising manager. He hates to sell ads,” she went on in a confiding tone. “But the newspaper needs more income. And I know all the store owners, so I don’t think I’d have any problem talking to them about taking out ads in the paper.”

Myra May gave her a sharp look. “If I’d known you were looking for a

job

, Ophelia, I would have asked if you wanted to work on the switchboard. I’ve had it up to here”—she put her hand to her forehead, above her eyebrows—“with sweet young things. I need someone mature.”

“Well, I’m mature, but I couldn’t,” Ophelia said apologetically, pushing her hair back behind her ear. “Jed wouldn’t want me to work nights or weekends. Mr. Dickens told me I could set my own hours at the

Dispatch.

Of course, it doesn’t pay much,” she added. “But it pays enough.”

Lizzy looked curiously at Ophelia. Enough for what? she wanted to ask, but she didn’t. Ophelia probably had a special project in mind. Maybe some more new furniture for her house, like that pretty living room suite she’d bought from Sears a while back. Lizzy admired that little walnut coffee table.

“I always heard that the Linotype was too big a machine for a woman,” Violet said, frowning. “Isn’t it hard to operate?”

“Not in the slightest,” Ophelia replied. “I think men just say that because they’re afraid that women will take their jobs.” She tilted her head to one side. “You have to have patience, yes, and it helps if you already know how to type. And I can’t lift a full case of type—not yet, anyway.” She lifted her arm and flexed her bicep. “But that may change. And I’m here to tell you that anybody who can operate a sewing machine and run up a dress pattern can certainly learn the Linotype.”

“That’s wonderful, Ophelia,” Bessie said. “Now, when I read the newspaper, I’ll know that you were the one who put all those words on paper.” She paused, looking around the table, as if to make sure that she had everyone’s attention. “Speaking of jobs, have you heard about Miss Rogers?”

“Uh-oh,” Verna said ominously. “Has the town council closed the library?”

“It doesn’t have to,” Ophelia put in. “Not for a while. That’s what Jed says, anyway. Somewhere, the council has found some money to keep it open.” She paused, frowning. “He didn’t tell me any of the details. I guess it’s not definite yet.”

Bessie dropped her voice. “The money your husband was talking about,” she said quietly, “is coming from the sale of Miss Rogers’ family heirlooms—the pillow and the documents that were hidden inside it.”

“She’s

sold

them?” Lizzy cried, alarmed. “Oh, no! They were really important to her!”

Bessie held up her hand. “It’s okay, truly, Liz. Now that she knows who her family was, she feels a lot less anxious about hanging on to a piece of the past. She decided to put the pillow and the documents to good use, so she sold them to a collector in Wilmington. He apparently has a few other things, including an autographed copy of Rose Greenhow’s memoir. He plans to donate everything to a local museum, where people can see them and understand what a courageous woman Miss Rogers’ grandmother was.”

Myra May clapped her hands. “Good for Miss Rogers,” she said. “I knew she had it in her—she just had to find it, that’s all.” On Violet’s lap, Cupcake clapped her hands and crowed happily, and they all laughed.

“And here’s the best part,” Bessie said. “Once the items are installed in the museum, she’ll be invited to Wilmington to see them. Isn’t that wonderful?”

“It really is,” Violet agreed. “Miss Rogers will love it.” She shook her head. “But I don’t see how any of that is going to help the library.”

“The money isn’t coming to Miss Rogers,” Bessie explained. “She’s giving it to the town council, with the stipulation that they use it to keep the library open—and let her use some of it for more books.”

“What a wonderful idea!” Lizzy exclaimed.

“More books,” Verna said. “I’m for that.”

“You bet,” Myra May replied emphatically.

“Let’s drink to Miss Rogers,” Ophelia said, lifting her lemonade glass.

“And to the Confederate Rose,” Bessie said.

“To the Confederate Rose,” they all said, in unison.

Rose Greenhow, Civil War Spy

The characters who appear in

The Darling Dahlias and the Confederate Rose

are entirely fictional—that is, except for the Confederate Rose herself: Rose O’Neal (sometimes spelled O’Neale) Greenhow, who was born in 1813 or 1814 and died by drowning on October 1, 1864. I have taken the story of her life, as it is related by Charlie Dickens in Chapter Sixteen, from a variety of sources, including

Wild Rose

, the excellent biography by Ann Blackman that appeared in 2005. If you’d like to learn more about Rose Greenhow, look for Blackman’s book.

Historians have debated the value of Rose’s spy craft and the importance of her espionage. Her coded dispatches were not the only secret information that General Beauregard received about the movement of Northern troops before the First Battle of Bull Run (as it was called by the North), but it is clear that the Confederate command placed a great deal of confidence in the intelligence she provided, which she obtained by listening to and asking questions of the government officials and military officers she entertained in her Washington home, on West Sixteenth Street, within sight of the White House.

Using a simple substitution cipher created by Colonel Thomas Jordan (whom espionage novelists would call her “spymaster”), Greenhow encrypted messages and concealed them in the clothing and other objects that her female friends wore or carried as they traveled from Washington to Manassas and Richmond. According to Blackman, Rose’s encrypted reports were “generally accurate and contained useful notes about the numbers and movements of Union forces around Washington.” Coded replies and requests for further information were carried back to Rose by Confederate couriers, usually Southern sympathizers, civilians who made their homes in Washington and were allowed to travel freely. This back-and-forth went on for months throughout 1861. Finally, the assistant secretary of war assigned Allan Pinkerton to establish a twenty-four-hour watch over her home, and, in early 1862, to place her under house arrest. When that did not stop her activities, she was imprisoned in the Old Capitol building, where she was held until her release and deportation to the South.

Rose bore eight children, including Little Rose, who had only one daughter, and it appears that there are no living Greenhow descendants. Miss Rogers’ relationship to Rose and Little Rose is entirely fictional, as is the embroidered pillow and the documents hidden within it. But such a thing is possible, don’t you think? And it makes a good story.

Rose Greenhow could not change the outcome of the War Between the States. But she did what she could to serve the Confederacy. And in the end, she died for it.

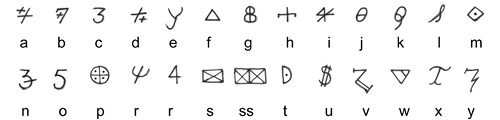

ROSE GREENHOW’S CIPHER

Credit: This cipher was redrawn by Peggy Turchette from the version reprinted on p. 176 in Fred Wrixon’s book, Codes, Ciphers, Secrets, and Cryptic Communication, Black Dog & Leventhal, 1998. The original is held by the North Carolina Office of Archives and History, Raleigh, North Carolina.

If there were no other reason to live in the South, Southern cookin’ would be enough.

—MICHAEL ANDREW GRISSOM,

SOUTHERN BY THE GRACE OF GOD

I have chosen recipes for this book that not only illustrate the wide range of foods that appeared on Southern tables during the early 1930s, but also have some historical interest, in terms of ingredients and preparation.

Dr. Carver’s Peanut Cookies #3

George Washington Carver was the most famous African American scientist and teacher of his era. He spent most of his professional life as a faculty member at Tuskegee Institute and was widely respected for his assistance to small farmers in improving their farming methods and his research into new uses for peanuts, sweet potatoes, pecans, and other Southern crops. He included recipes in his agricultural bulletins in order to demonstrate a variety of uses for the crops. This popular recipe is from

How to Grow the Peanut and 105 Ways of Preparing it for Human Consumption,

Tuskegee Institute Press, Bulletin Number 31, June 1925.

1

⁄

3

cup butter

2 eggs, well beaten

1

⁄

2

cup sugar

1

⁄

2

cup flour

1

⁄

2

teaspoon baking powder

1

⁄

2

cup finely chopped peanuts

1 teaspoon lemon juice

3

⁄

4

cup milk

Cream butter and add sugar and eggs. Sift the flour and baking powder together. Combine the butter and flour mixtures. Then add the milk, nuts, and lemon juice. Mix well and then drop mixture from a spoon to an unbuttered baking sheet. Sprinkle with additional chopped nuts and bake in a slow oven (about 300 degrees). Makes about 2 dozen cookies.

Lizzy Lacy’s Buttermilk Pie

This old-fashioned, easy-to-put-together pie is a longtime favorite in Southern families, for many had their own milk cow. But before refrigeration was developed, milk soured quickly in the warm climate of the South, so the cream was churned into butter, which could be preserved almost indefinitely in brine. Buttermilk, the liquid that remained in the churn after the butter formed, was mildly tart and very refreshing. Cultured buttermilk, the product that you see in the dairy case at your local supermarket, is lightly fermented, pasteurized skim milk. It is not nearly as rich as the buttermilk our great-grandmothers used, but it is still an effective ingredient. If you don’t have buttermilk, you can create an acceptable substitute by adding 1 tablespoon of lemon juice or white vinegar to 1 cup of fat-free, skim, or whole milk.

1

⁄

2

cup butter, room temperature

2 cups sugar

3 eggs

2 rounded tablespoons flour

1 cup buttermilk

Dash of nutmeg

1 teaspoon vanilla

Zest (grated rind) of two lemons

Unbaked 9-inch pie shell

Cream butter and sugar. Mix eggs and flour and beat into the butter/sugar mixture. Stir in buttermilk, nutmeg, vanilla, and lemon zest (if you have it). Pour into the pie shell and bake at 350 degrees for 45 minutes. The top should be lightly browned and the center should jiggle. Don’t overbake—the pie will set as it cools.

The Darling Diner Grits

In the South, breakfast without grits isn’t breakfast. Grits (or hominy grits) were adapted from a cooked mush of softened maize eaten by Native Americans. It was likely introduced to the colonists at Jamestown around 1607 by the Algonquin Indians, who called it

rockahominy

,

meaning hulled corn. The word grits comes from the Old English

grytt

(bran) or

greot

(ground) and is usually treated as a singular noun. The colonists made grits by soaking corn in lye made from wood ash until the hulls floated off. It was then pounded and dried. Modern grits (also called

hominy

, derived from

rockahominy

) is made without lye. Most Southerners prefer stone-ground grits to instant or quick-cook grits because the germ is still intact and it simply tastes better. Grits may be served with sausage or ham, with bacon and eggs, baked with cheese, or sliced cold and fried in bacon grease (my mother’s favorite way of serving it).

1 cup stone-ground grits

Water for rinsing

4 cups water

1

⁄

2

teaspoon salt

2 tablespoons unsalted butter, divided into 4

To rinse, pour the grits into a large bowl and cover with cold water. Skim off the bits of floating chaff, stir, and skim again. Drain in a sieve. Bring 4 cups of water to a boil in a large pan. Add salt and gradually stir in the grits. Reduce heat and simmer, stirring often, until the grits are thick and creamy, about 40 minutes. Pour into four bowls and stir in butter.

Euphoria’s Southern Fried Doughnuts

Since Euphoria bakes a great many meringue pies, the diner’s kitchen is equipped with an electric beater, which also makes short work of mixing up a batch of doughnuts. (In their 1929 catalog, Sears and Roebuck sold a stand model, manufactured by Arctic, for nine dollars and ninety-five cents.) This recipe makes about a dozen doughnuts, a sweet alternative to biscuits for a Southern breakfast. Other traditional recipes include sweet potato doughnuts, mashed potato doughnuts, and

calas

, New Orleans doughnuts (rather like fritters) made from cooked rice, eggs, flour, and sugar.

2 tablespoons lukewarm water

1 teaspoon sugar

1 (

1

⁄

4

-ounce) package active dry yeast (2

1

⁄

4

teaspoons)

3

1

⁄

4

cups flour

1 cup milk

1

⁄

2

stick (4 tablespoons) unsalted butter

2 large eggs

2 tablespoons sugar

1

1

⁄

2

teaspoons salt

1

⁄

2

teaspoon cinnamon

5 to 6 cups vegetable oil (for frying)

To proof yeast (that is, to make sure that it’s fresh and active), place warm water in shallow bowl. Stir in sugar until dissolved. Sprinkle yeast across the solution and stir until dissolved. Let stand for 5 to 7 minutes. Fresh yeast will bubble. If it doesn’t, toss it out and try again with fresh yeast.

Combine flour, milk, butter, eggs, sugar, salt, and cinnamon in large mixer bowl and add yeast mixture. Mix at low speed until a soft dough forms, then increase to high and beat for 3 minutes. Scrape dough from sides of bowl and brush lightly with oil. Cover with a damp towel and let rise in a warm place until doubled in bulk, 1

1

⁄

2

to 2 hours, or let rise in refrigerator overnight (8 to 12 hours).

Turn dough onto a lightly floured surface and roll about

1

⁄

2

-inch thick. Using a doughnut cutter, cut out rounds. (Reroll doughnut centers and recut to make 1 or 2 additional doughnuts.) Cover with a damp towel and let rise until slightly puffed, about 30 minutes (45 minutes if dough was refrigerated). Heat oil to 350ºF in a heavy 4-quart pot. Fry 2 doughnuts at a time, turning once or twice with a slotted spoon, until golden brown and puffy (about 2 minutes). Drain. Reheat oil to 350ºF before frying the next batch. Cool and glaze.

GLAZE

1

⁄

4

cup milk

1 teaspoon vanilla

2 cups confectioners’ sugar

Heat milk and vanilla in a medium saucepan until warm. Sift confectioners’ sugar into milk and whisk until well mixed. Remove from heat and place over a bowl of warm water. Dip cooled doughnuts individually into the glaze. Drain on a rack over a cookie sheet.

Aunt Hetty Little’s Stewed Okra with Corn and Tomatoes

Okra (

Hibiscus esculentus,

a member of the same family as the Confederate rose) grows well in the heat and humidity of the South and is a staple of Southern gardens—and Southern cooking. The plant seems to have originated in Ethiopia, then distributed to the eastern Mediterranean, Arabia, and India. A Spanish Moor visiting Egypt in 1216 wrote one of the earliest accounts of okra’s use as a vegetable, reporting that the young seedpods were cooked with meal to reduce their gummy texture. In the American South, cooks follow something of the same practice, dipping the sliced pods in cornmeal and frying them.

During the Civil War, okra seeds were dried, parched, and brewed as a coffee substitute. This recipe is from

the

Southern Banner,

Athens, Georgia, February 11, 1863: “Parch over a good fire and stir well until it is dark brown; then take off the fire and before the seed gets cool put the white of one egg to two tea-cups full of okra [seed], and mix well. Put the same quantity of seed in the coffeepot as you would coffee, boil well and settle as coffee.”

3 to 4 strips bacon, diced

1

⁄

2

cup diced onion

3 to 4 cloves garlic, diced

8 to 10 pods fresh young okra, sliced

1 cup corn kernels

1

⁄

2

cup diced green peppers

1 cup diced tomatoes

1 cup tomato sauce

1

⁄

2

cup water

1

⁄

4

teaspoon red pepper flakes

1

⁄

2

teaspoon dry thyme

1

⁄

2

teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon black pepper

Sauté diced bacon, add onion and garlic, and sauté until onions are transparent. Add all other ingredients and bring to a boil. Reduce to a simmer and cook, stirring occasionally, for 35 to 40 minutes or until okra is tender.

Mildred Kilgore’s Southern Coleslaw

No Southern celebration would be complete without a big bowl of coleslaw. The word comes from the Dutch words,

kool sla

(cabbage salad, usually served hot). This recipe, which features a sharply sweet-sour dressing, is picnic-perfect, a vinegary foil to a platter of fried chicken or barbequed ribs. Celery seed was a favorite Southern flavoring, especially recommended for use with cabbage.

1 pound finely shredded cabbage

1 medium red onion, quartered and finely sliced

1 cup toasted pecans, chopped

DRESSING

1 cup sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1

1

⁄

2

teaspoons dry mustard

1 teaspoon celery seed

1 cup vinegar

2

⁄

3

cup vegetable oil

Combine shredded cabbage with sliced onion and pecans. Combine dressing ingredients and bring to a boil. Pour over cabbage and toss. Serve warm or chilled.