The Daughter of Siena

Table of Contents

2

-

The Tortoise

3

-

The Eagle

4

-

The Wave

5

-

The Panther

6

-

The Forest

7

-

The She-Wolf

8

-

The Goose

9

-

The Unicorn

10

-

The Dragon

11

-

The Giraffe

12

-

The Vale of the Ram

13

-

The Snail

14

-

The Caterpillar

15

-

The Porcupine

16

-

The Tower

17

-

The Shell

EPILOGUE

-

The Sixteenth Day of August 1724

Also by Marina Fiorato

HISTORICAL NOTE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

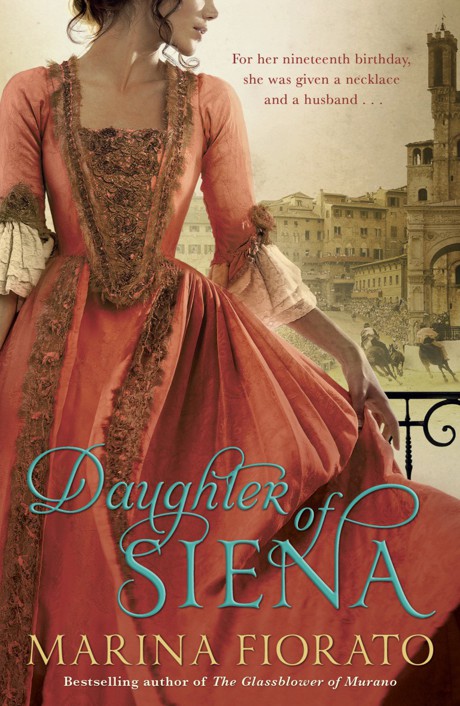

THE DAUGHTER OF SIENA

Copyright Page

-

The Tortoise

3

-

The Eagle

4

-

The Wave

5

-

The Panther

6

-

The Forest

7

-

The She-Wolf

8

-

The Goose

9

-

The Unicorn

10

-

The Dragon

11

-

The Giraffe

12

-

The Vale of the Ram

13

-

The Snail

14

-

The Caterpillar

15

-

The Porcupine

16

-

The Tower

17

-

The Shell

EPILOGUE

-

The Sixteenth Day of August 1724

Also by Marina Fiorato

HISTORICAL NOTE

AUTHOR’S NOTE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THE DAUGHTER OF SIENA

Copyright Page

The Donkey

T

wo gentlemen of Siena stared down at a stinking corpse that had been flung over the wall at the Camollia gate.

wo gentlemen of Siena stared down at a stinking corpse that had been flung over the wall at the Camollia gate.

‘Is it a horse?’ asked the younger, for the body was so decomposed it was hard to tell.

‘No, it’s a donkey,’ answered his elder.

‘Hmm.’ The youth was thoughtful. ‘Whatever can it mean?’

‘Well,’ said the other, who was pleased to be asked, and whose air of the greybeard who knew it all did not endear him to his friends, ‘in 1230 the Florentines who besieged Siena used to throw the corpses of donkeys over the city walls. They hoped the carcasses would bring pestilence and plague.’

The youth pulled his neckerchief swiftly over his nose and mouth. ‘Jesu. D’you think this one is diseased? It stinks enough.’

‘Dio

. It’s not the olden days. Someone’s ass died and they dumped it. No more, no less.’

. It’s not the olden days. Someone’s ass died and they dumped it. No more, no less.’

His companion craned upwards and stroked the beard

that he one day wished to have. ‘I don’t know. Look; there’s some blood and skin on the top of the gate. This fellow was thrown over. Should we tell someone?’

that he one day wished to have. ‘I don’t know. Look; there’s some blood and skin on the top of the gate. This fellow was thrown over. Should we tell someone?’

‘Like who?’

‘Well, I don’t know … the duchess? The council, then? Or the Watch?’

The older man turned towards his young companion. He had never known the lad to question with him and felt justified in hardening his tone just a little.

‘The Watch?’ he scoffed. ‘On the eve of the Palio? D’you not think they might have better things to worry about than a dead donkey?’

The boy hung his head. He supposed he was right. It was the Palio tomorrow and the whole city was a ferment of excitement, a ferment that sometimes bubbled over into violence. Nevertheless, he walked backwards for a little until he could no longer see the grisly heap. Intensely superstitious, like all Sienese, he could not help thinking that the donkey was an ill omen for the city. Uneasy little thoughts gathered round his head like the flies that rose from the corpse.

The Owlet

F

or her nineteenth birthday, Pia Tolomei, the most beautiful woman in Siena, was given a necklace and a husband.

or her nineteenth birthday, Pia Tolomei, the most beautiful woman in Siena, was given a necklace and a husband.

Her name-day was spent sitting quietly in her chamber, a day like any other – the same, the same, the same. But then Pia’s maid told her that her father wished to see her and she knew exactly what was coming. She’d been awaiting this moment since she was eleven.

She laid down her hoop of embroidery with a shaking hand and went down to the

piano nobile

at once. Her knees shook too as they carried her slight and upright form down the stair, but she had courage. She knew it was time to face what she had dreaded for years, for as long as she had been old enough to understand the expediencies of the marriage market.

piano nobile

at once. Her knees shook too as they carried her slight and upright form down the stair, but she had courage. She knew it was time to face what she had dreaded for years, for as long as she had been old enough to understand the expediencies of the marriage market.

For eight years Pia had expected, daily, to be parcelled up and handed in marriage to some young sprig of Sienese nobility. But fate had kept her free until now. Pia knew that her father

would not marry her beyond her ward, the

contrada

of the Civetta, the Owlet. And here she had been fortunate, for the male heirs of the good Civetta families were few. A boy that she was betrothed to in the cradle had died of the water fever. Another had gone to the wars and married abroad. The only other heir she could think of had just turned fifteen. She had a notion her father had been waiting for this lad to reach his majority. She went downstairs now, fully expecting that she was about to be shackled to a child.

would not marry her beyond her ward, the

contrada

of the Civetta, the Owlet. And here she had been fortunate, for the male heirs of the good Civetta families were few. A boy that she was betrothed to in the cradle had died of the water fever. Another had gone to the wars and married abroad. The only other heir she could think of had just turned fifteen. She had a notion her father had been waiting for this lad to reach his majority. She went downstairs now, fully expecting that she was about to be shackled to a child.

In the great chamber her father Salvatore Tolomei stood in a shaft of golden light streaming in through the windows. He had always had an instinct for the theatrical. He waited until she approached him and laid her cool kiss upon his cheek, before he pulled a glittering gold chain from his sleeve with a magician’s flourish. He laid it in her palm where it curled like a little serpent and she saw that there was a roundel, or pendant, hanging from it.

‘Look close,’ Salvatore said.

Pia obeyed, humouring him, masking the impatience she felt rising within her. She saw a woman’s head depicted on a gold disc, decapitated and floating.

‘It is Queen Cleopatra herself,’ whispered Salvatore with awe, ‘on one of her own Egyptian coins. It is more than a thousand years old.’

His ample form seemed to swell even further with pride. Pia sighed inwardly. She had grown up being told, almost daily, that the ancestors of the Tolomei were Egyptian royalty, the Ptolemy. Salvatore Tolomei – and all the Civetta

capitani

before him – never stopped telling people of the famous Queen Cleopatra from whom he was directly descended.

capitani

before him – never stopped telling people of the famous Queen Cleopatra from whom he was directly descended.

Pia felt the great weight of her heritage pressing down on her and looked at the long-dead queen almost with pity. That her long, illustrious royal line should distil itself down into Pia, the Owlet, daughter and heir to the house of the Owls! Pia was queen of nothing but the Civetta

contrada

, sovereign of a quiet ward in the north of Siena, regent of a collection of ancient courtyards and empress of a company of shoemakers.

contrada

, sovereign of a quiet ward in the north of Siena, regent of a collection of ancient courtyards and empress of a company of shoemakers.

‘And on the other side?’

Pia turned the coin over and saw a little owl in gold relief.

‘Our own emblem, and hers; the emblem of Minerva, of Aphrodite, of Civetta.’

She looked up at her father, waiting for the meat of the matter. She knew he never gave without expectation of return.

‘It is a gift for your name-day, but also a dowry,’ said he. ‘I have spoken with Faustino Caprimulgo of the Eagle

contrada

. His son, Vicenzo, will take you in marriage.’

contrada

. His son, Vicenzo, will take you in marriage.’

Pia closed her hand tight around the coin until it bit. She felt a white-hot flame of anger thrill through her. She had not, of course, expected to choose her own husband, but she had hoped in her alliance with the Chigi boy that she could school him a little, to become the most that she could wish for in a husband; to treat her with kindness and leave her alone. How could her father do this? She had always,

always

done as Salvatore asked, and now her reward was to be a marriage to a man she not only knew to be reviled, but a man from another

contrada.

It was unheard of.

always

done as Salvatore asked, and now her reward was to be a marriage to a man she not only knew to be reviled, but a man from another

contrada.

It was unheard of.

She knew Vicenzo by repute to be almost as villainous and cruel as his father, the notorious Faustino Caprimulgo. The Caprimulgo family, captains of the Eagle

contrada,

was one of the oldest in Siena, but the nobility of the antique family was

not reflected in its behaviour. Their crimes were many – they were a flock of felons, a murder of Eagles. Pia was too well bred to seek out gossip but the stories had still reached her ears: the murders, the beatings, Vicenzo’s numerous violations of Sienese women. Last year a girl had hanged herself from her family’s ham-hook. She was barely out of school. ‘With child,’ Pia’s maid had said. ‘Another Eagle’s hatchling.’ Apparently Salvatore could overlook such behaviour in the light of an advantageous match.

contrada,

was one of the oldest in Siena, but the nobility of the antique family was

not reflected in its behaviour. Their crimes were many – they were a flock of felons, a murder of Eagles. Pia was too well bred to seek out gossip but the stories had still reached her ears: the murders, the beatings, Vicenzo’s numerous violations of Sienese women. Last year a girl had hanged herself from her family’s ham-hook. She was barely out of school. ‘With child,’ Pia’s maid had said. ‘Another Eagle’s hatchling.’ Apparently Salvatore could overlook such behaviour in the light of an advantageous match.

‘Father,’ she said, ‘I cannot. You know what they say of him – what happened to the Benedetto girl. And he is an Eagle. Since when did an Eagle and an Owlet couple?’

In her mind she saw these two birds mating to create a dreadful hybrid, a chimera, a griffon. Wrong, all wrong. Salvatore’s face went still with anger and at the same instant she heard the scrape of a boot behind her.

He was

here.

here.

Pia turned slowly, a horrible chill creeping over her flesh, as Vicenzo Caprimulgo walked forth from the shadows.

A strange trick of light caught his nose and eyes first. A beak and two beads – like the stuffed birds in her father’s hunting lodge. His thin mouth was curved in a slight smile.

‘I am sorry, truly, that the match does not please you.’ His voice was calm and measured, with only a whisper of threat. ‘Your father and I have a very particular reason for this alliance between our two

contrade

. But I am sure I can … persuade you to think better of me, when you know me better.’

contrade

. But I am sure I can … persuade you to think better of me, when you know me better.’

Pia opened her mouth to say that she had no wish to know him better, but she was too well bred to be insolent, and too afraid to speak her mind.

‘It’s something you can do at your leisure, for your father has agreed that we will marry on the morrow, after the Palio, which I intend to win.’

He came close and she could feel his breath on her cheek. She had never been this close to a man save her father.

‘And I assure you, mistress, that there are certain arenas in which I can please you much better than a fifteen-year-old boy.’

The malice in his eyes was unmistakable. There was something else there too: a naked desire, which turned her bones to water. She shoved straight past him and back up the stairs to her chamber, her father’s apologies raining in her ears. He was not apologizing to her, but to Vicenzo.

Alone in her chamber, Pia paced the floor, fists clenched, blood pounding in her head. Below she could hear the final preparations being made for the celebratory feast she had believed was for her own name-day. How could her life be overturned in this way?

Several times during the evening Salvatore sent servants to knock at her door. She ignored them: the celebrations would go on whether she was there or not. Despairing and frightened, she sat huddled in a chair as dusk fell, hungry and shivering, although it was not cold.

Eventually her father came himself and she could not refuse his bidding. She was to take a turn about the courtyard with Vicenzo, he said, to admire the sunset. The servants were all inside. It would be a chance for her to get to know her husband.

Pia did as she was commanded and walked Vicenzo to his horse as the sinking sun gilded the ancient stones. Still frozen by shock, she made no attempt to converse with him, and by the time they had crossed the courtyard his sallies and courtesies

had turned to scorn and provocation. Numbly, she observed how the shadows of twilight closed around her. She took him, unspeaking, to the loggia where his horse was tied and waited silently for him to mount. Suddenly he lunged at her, spinning her behind the darkest pillar. His hungry lips mouthed at her neck and his greedy hands snatched at her breasts.

had turned to scorn and provocation. Numbly, she observed how the shadows of twilight closed around her. She took him, unspeaking, to the loggia where his horse was tied and waited silently for him to mount. Suddenly he lunged at her, spinning her behind the darkest pillar. His hungry lips mouthed at her neck and his greedy hands snatched at her breasts.

‘Come,’ he whispered viciously, ‘the contracts are inked, you are nearly mine, so nearly.’

She fought him then, desperately crying out, although there was no one to hear, striking him about the face and chest. Her struggles only seemed to madden him more, and when he grabbed her by the hair and threw her through the half-door of the stable she thought she was lost. She smelled the warm straw and tasted the tang of blood where she’d bitten her cheek. But Vicenzo seemed to check himself.

‘Stay pure, then, for one more night,’ he spat, as he stood over her, ‘for tomorrow I’ll take you anyway.’ He turned in the doorway. ‘And never strike me again.’

Then he kicked her, repeatedly, not about her peerless face, but on her body, so the bruises would be hidden under her clothes.

When at last he was gone the shock hit her and she retched, great dry heaves, into the straw. In the warm dark she could hear the Civetta horses, snorting and shifting, curious.

She straightened up, aching, and walked directly out of the courtyard straight to the Civetta church across the piazza. She laid her hands on the heavy doors that she had passed through for years, for her christening, confirmation and shrift. Tonight she did not tenderly lift the latch but hurled the oak doors open so they slammed back against the pilasters, sending angry

echoes through the belly of the old church. She ran to the Lady Chapel and there her legs gave way, her knees cracking on the cold stone. She prayed and prayed, the pendant pressed hard between her palms. Not once did she look up at the images of the Christ or Mary; she was calling on far more ancient deities for help. She thought it more likely that the antique totem between her hands could help her. She prayed for something to happen, some calamity to release her from this match. When she opened her hands there was the imprint of Cleopatra on one palm and the owlet on the other.

echoes through the belly of the old church. She ran to the Lady Chapel and there her legs gave way, her knees cracking on the cold stone. She prayed and prayed, the pendant pressed hard between her palms. Not once did she look up at the images of the Christ or Mary; she was calling on far more ancient deities for help. She thought it more likely that the antique totem between her hands could help her. She prayed for something to happen, some calamity to release her from this match. When she opened her hands there was the imprint of Cleopatra on one palm and the owlet on the other.

Other books

Timeline by Michael Crichton

Jude (A Cocky Cage Fighter Novel Book 2) by Hart, Lane

The Bride Backfire by Kelly Eileen Hake

Marked for Life by Emelie Schepp

The Chinese Takeout by Judith Cutler

Ham by Sam Harris

Mistress of Mourning by Karen Harper

Arena Two by Morgan Rice

John Gone by Kayatta, Michael