The Day We Went to War (51 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

In Berlin on that same day, thirty-three-year-old William Joyce received a contract as a newsreader on the German Radio Corporation. Anybody less like Bertie Wooster would be hard to imagine, but in the weeks to come, by a ‘single-minded determination, ruthless ambition and sheer application’, Joyce became “Lord Haw Haw”: the English Voice of Germany’.

Joyce had been born in New York on 24 April 1906 to naturalised American citizens. In 1909, the Joyce family returned to their native Ireland. As staunch supporters of the British cause, when Ireland was partitioned in 1922, the Joyces thought it prudent to move to England. It was not long before the ultra-patriotic William developed a taste for extreme right-wing politics, joining the British Fascists when only seventeen. Ten years later, Joyce joined Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists and within a short time became Deputy Leader. In public Joyce called Sir Oswald ‘the greatest Englishman I have ever known’, but in private was scathing of him, ‘Mosley was hopeless. He was the worst leader of what should have been the best cause in the world.’ In 1937, matters came to a head, and Mosley dismissed his deputy. Joyce founded his own National Socialist League which, with its violently antisemitic and pro-Nazi programme, attracted only a tiny membership.

On 24 August 1939, with war imminent, Joyce decided, ‘England was going to war. I felt that if, for perfect reasons of conscience, I could not fight for her, I must give her up forever.’ Accordingly, and with his second wife Margaret, he set out for Berlin. Anxious to play his own small part in Hitler’s ‘sacred struggle to free the world’, Joyce applied for a job at the German Radio Corporation. His initial voice test did not go well, but an engineer thought that Joyce’s voice had potential, and he first spoke over the air on 11 September, receiving a contract a week later.

Obviously the Lord Haw Haw that Barrington heard that week could not have been Joyce. It was most probably Wolff Mittler, a German ‘playboy of the first order’, who used to sign off his broadcasts with ‘Hearty Cheerios!’ to his listeners. But it was Joyce who soon established his own claim on the title. In this he was aided by the British public’s enormous interest in the broadcasts. This was undoubtedly because ‘in no other war had the British enjoyed the novelty of being cajoled and hectored by renegades in their own sitting rooms’, but also by the relative lack of war news. And it was not long before Lord Haw Haw became the ‘Number One Radio Personality of the War’, and the major topic of conversation. In the press too, items about him filled the correspondence columns. There was endless speculation about Haw Haw’s social origins, education and accent. In Berlin, Dr Goebbels, gratified at the size of the British audience for Joyce’s broadcasts, told an American correspondent:

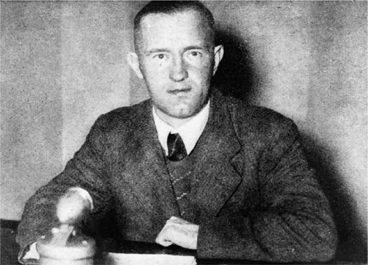

‘Jairmany calling, Jairmany calling.’ William Joyce, Lord Haw Haw, at the microphone. ‘I think that, secretly, we are rather terrified by the appalling things he says. The cool way he tells us of the decline of democracy and so on. I hate it; it frightens me. Am I alone in this? Nobody has confessed as much to me.’

‘Can you imagine what is one of the chief discussions about it across the Channel? It is, whether our German [

sic

] announcer has an Oxford or Cambridge accent! In my opinion, when a people in the midst of a life-and-death struggle indulge in such frivolous arguments, it doesn’t look well for them.’

Many found the whole idea of treason by radio repugnant. ‘What can have induced an Englishman, if he is an Englishman, to behave in such a sickening renegade manner?’ asked Mr A.R. Thomas of Bournemouth in

News Review

on 19 October. But a Mr Heath, quoted in

Illustrated

of 4 November, thought that ‘Lord Haw Haw was funnier than anything that the BBC ever put on.’ This was a view shared by a Canadian listener whose letter appeared in

London Calling

three weeks later: ‘Whenever we are short of entertainment we tune in to that comedian. We often wonder whether he knows what a lot of laughter he causes.’

But it was not always laughter that Joyce’s broadcasts engendered. That Christmas, a Mass Observation correspondent asked an aunt, ‘a very patriotic Conservative woman’, what she thought of Lord Haw Haw. He was surprised at her response: “Oh I don’t listen to him now. I am not going to be frightened by him. And it’s no use calling what he says rubbish, because there’s never smoke without fire!” And,’ he added, ‘

she

thinks that everything in Germany’s bad.’

Another Mass Observation correspondent was of the opinion: ‘I think that, secretly, we are rather terrified by the appalling things he says. The cool way he tells of us of the decline of democracy

and so on. I hate it; it frightens me. Am I alone in this? Nobody has confessed as much to me.’

There was no shortage of advice on how to combat the effectiveness of Lord Haw Haw’s broadcasts. In the 25 November issue of

Picture Post

, Mr A.E. Waugh of Sheffield offered his solution: ‘My part in the radio war. I put on the radio to listen to the Hamburg announcer, he is so amusing. When he has done, my daughter and I give him the Raspberry. Only sorry he can’t hear what we say.’ In the same magazine, Londoner Mr C.N. Edge suggested, ‘Could the BBC therefore be persuaded to give each night immediately after Haw-Haw’s talk, a ten minute “Spot The Errors” item on the “Inspector Hornleigh” principle, with a run through of Haw-Haw’s speech, and then STOP. The announcer pointing out the errors or mis-statement.’

This suggestion had already been the subject of at least two memoranda at the BBC, where Sir Stephen Tallents had been told by the Countess of Harrowby: ‘My hostess’s servants listen in to Haw-Haw, and one of them remarked the other day there was probably something in what he said . . . thousands of people like those maids listen to him daily and find themselves influenced by his malicious lies.’

Others when listening to Joyce took the view of an RAF airmen: ‘He talks a lot of cock and 75 per cent of his statements are either lies or propaganda, but occasionally he hits the nail on the head, it’s then that he makes you think. You wonder whether a lot of his statements are true.’ And a woman librarian said, ‘We nearly always turn him on at 9.15 to try and glean some news that the Ministry of Information withholds from us. It is interesting to get the BBC’s views and the German wireless’s accounts of the same aerial engagements. Between the frantic eulogies of the BBC and the sneers of the German wireless one achieves something like the truth.’

As the year ended, the BBC and Ministry of Information were still agonising on how best to deal with Lord Haw Haw. One idea

was to put leading show-business personalities like Arthur Askey, Gracie Fields or George Formby on the BBC at the same time that Lord Haw Haw was broadcasting from Hamburg. Like them, he was now a distinct personality in his own right, even featuring in advertisements like one for Smith’s Electric Clocks, ‘Don’t risk missing Haw-Haw. Get a clock that shows the right time always, unquestionably.’ At the Holborn Empire that month, impresario George Black put on a revue entitled

Haw Haw

, starring Max Miller. To Black, ‘the thought of Haw-Haw’s regimented voice having the slightest connection with the endearing, confidential vulgarities of Miller had a delicious fantasy about it.’ And two other music-hall comedians, the Western Brothers, had a hit with their song ‘Lord Haw Haw the Humbug of Hamburg’.

C

HAPTER

15

The Winter War

Russia Invades Finland: 30 November 1939

Following his occupation of eastern Poland, Stalin set about consolidating his sphere of influence in the Baltic, assigned to him under the terms of the secret protocols of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The Soviet dictator was still deeply suspicious of his new ‘ally’, and wished to gain as much buffer territory between him and Hitler as possible. So-called mutual assistance pacts were signed with the small Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, all of which were forced to agree to Soviet demands for military bases on their territory.

From Finland, Stalin required a similar agreement, and the Finns sent veteran statesman J.K. Paasikivi to Moscow to negotiate the Soviet demands with the Kremlin. There, Paasikivi found that the Russians wanted a mutual assistance pact, the occupation of the southern part of the Karelian Isthmus, the leasing of the port of Hango as a naval and air base, the cession of islands in the Baltic, and the leasing of the Rybachi Peninsula on which was Petsamo, Finland’s only ice-free port. In return the Russians offered 2,134 square miles of Soviet Karelia, considered by the Finns as worthless.

Negotiations between the two sides, in which Stalin himself played a considerable part, eventually broke down. The Finns mobilised their forces, under Field Marshal Carl Gustav Mannerheim, along the frontier and waited for the inevitable.

On 26 November, the Soviets fabricated a border incident, and four days later, after severing diplomatic relations but without a declaration of war, launched an all-out attack on Finland. Soviet bombers raided Helsinki, and the Finnish capital was soon experiencing what Warsaw had gone through in September. A British United Press correspondent graphically described it:

‘When the first bomb was dropped I was thrown to the floor. All the windows of the hotel were shattered. Being none the worse for my fall, I telephoned the City Exchange in order to get a trunk call. The telephone girl was still at her post and quite coolly got me my number. I counted at least a dozen bombs, two of which were huge and shattered windows over a radius of about half a mile. Incendiary bombs were dropped, evidently aimed at the airport. They went wide and started several fires in the centre of the city. The heavy bombs were presumably for the railway station, but a motor bus got the worst of one and a number of people in it were killed. There was pandemonium from continuous anti-aircraft gunfire . . . The raid had come practically without warning. The first bombs dropped barely one minute after the sirens were sounded. There was no panic, but many people appeared too dazed to make for the cellars and stood stupefied, staring up into the sky. City transport was paralysed. In one area, the fire department took charge, and the firemen began digging in the debris to recover bodies . . . The darkness, which came down at 4pm, was broken by winking flashlights of citizens picking their way through the rubble, and by the glare from burning buildings where rescue work was still going on.’

In a political blunder of the first magnitude, the Soviets set up, at the border village of Terijoki, a puppet government under the veteran Finnish Communist exile Otto Kuusinen. This only served to unite the Finnish people even more behind the new legitimate government of Rysto Ryti, former Governor of the Bank of Finland, who reaffirmed Finland’s will to resist. Seventy-two-year-old aristocrat Mannerheim issued a stirring Order of the Day to his men, calling on them to ‘fulfil their duty even under death. We fight for our homes, our faith, our fatherland.’

Finland’s commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Carl Gustav Mannerheim. Meeting the Field Marshal in 1938, Lady Diana Cooper wrote, ‘the great Field-Marshal Mannerheim was there. He made Finland and is treated half-royal, half-Godhead. He looks fifty and is said to dye his hair . . . and he is only seventy-two. He is an old Russian Imperialist (that I find irresistible) and says in French “pardon”.’

The Soviet invasion was deplored by statesmen throughout the world. President Roosevelt said how ‘all peace-loving peoples . . . will unanimously condemn this new resort to military force . . .’ And in the Commons, Chamberlain stated that his government ‘deeply regret this attack on a small independent nation, which must result in fresh suffering and loss of life to innocent people’. Ordinary people shared their governments’ disgust at the Soviet action. On 4 December, Auxiliary Firewoman Elsie Warren wrote in her diary, ‘Russia is still bombing Finnish towns. The town [

sic

] of Helsinki is suffering the most. Stalin made as if to be friendly with the Finns; even wishing them “Good Luck!” The Finnish women and children returned to their homes after having been evacuated thinking that all was well. Suddenly without warning and refusing to negotiate on the matter Russia invaded Finland. She rained bombs from the air on towns killing helpless women and children. The rest of the world were disgusted.’