The Day We Went to War (48 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

But there was another and a much brighter side to the evacuation coin. Queen Elizabeth, on one of her visits to evacuated families, called on Mrs Bridge, the wife of an electrical engineer in the Royal Navy. At her home in Birdham, near Chichester, Mrs Bridge had eighteen children to look after, seven of her own and eleven evacuees. She began her day at 5am, cooking eighteen breakfasts of porridge. Then she sent the children to school, where they got lunch. Every other evening each child had a hot bath. The children did their homework in one room, and played games in another. ‘A wonderful woman’, was the Queen’s comment.

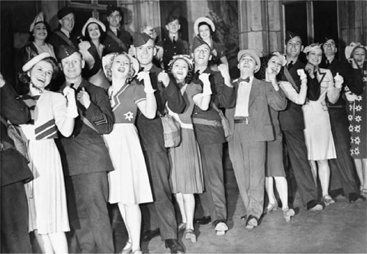

Queen Elizabeth visits evacuated children ‘somewhere in Sussex’, 8 November 1939. The Queen later sent a personal message of appreciation to those who had taken in evacuees: ‘By your sympathy you have earned the gratitude of those to whom you have shown hospitality, & by your readiness to serve you have helped the State in a work of great value.’

And among the thousands of letters that

Picture Post

received on the subject there was one from Mrs E.A. Hemming of Great King Street, Hockley, Birmingham, who wrote, ‘My son, just six years old, has been evacuated to Monmouth, South Wales. I went to see him on Sunday, and I can’t really express my gratitude and how much I appreciate the kindness shown to him and myself in the wonderful way in which we were welcomed. I didn’t think there was so much kindness in this world. If you could see the smiling faces in Monmouth, it would do you a world of good.’

And a middle-aged couple in Kettering told the magazine that they had always wanted children, and now, at last they had them: ‘They scream and race about the place and yesterday the little girl was sick on the drawing room carpet. But that’s what we have always wanted. Thank God for our little evacuees!’

Fear of devastating air raids brought about the mass slaughter of domestic animals in the first few days of the war. Some estimates put the number of animals destroyed at 2,000,000, but the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA) calculated that around 200,000 dogs had been put down. In the East End of London there was a ‘secret burial-ground’ near excavations for a Tube extension. According to the

Sunday Express

, 80,000 animal carcasses were buried there in one night. As well as the danger from air raids, many animal lovers had their pets put down because they feared there would be no food for them anyway. Thousands of others claimed that there had been a Government announcement ordering the compulsory destruction of cats and dogs. For those pets retained by their owners, the People’s Dispensary for

Sick Animals (PDSA) offered gas-proof kennels at £4 each, while gas masks for dogs retailed at £9 a time. In London’s Hyde Park, the Air Raid Precautions Animals Committee put up a large number of white posts, with leads and chains, for dog owners to attach their pets before going down into the park’s trench shelters.

Writing to the

Topical Times

, Mr E.J. Foster of 2 Hazel Avenue, North Shields came up with his own solution to the problem of how to protect pets in gas attacks, earning himself five shillings (25p) in the process: ‘In wartime, a grand way to stop pet birds (budgies, canaries &c) from being gassed is to wrap a wet towel around the cage and so exclude all poison gas. Another way is to put the cage in the bathroom and close all windows and door. Then turn on the hot taps and so fill the room with steam. The steam keeps away all gas which may seep in.’

London Zoo evacuated some of its animals, including the elephants and pandas, to Whipsnade. Others, especially the whole collection of poisonous and constrictor snakes and black-widow spiders, were given a lethal dose of chloroform by their keepers. The aquarium, which if it had been hit by bombs would have released 200,000 gallons of water, was emptied and used as a storehouse for newsprint and paper. During air-raid alerts that autumn and winter, posses of keepers at London Zoo and at the Scottish Zoological Park at Edinburgh were armed with Lee Enfield rifles with instructions to shoot any larger flesh-eating animals which might escape in the bombing and be a danger to the public.

But some animals were in danger themselves, as the

Daily Express

reported on 23 October:

WATCH YOUR CATS – THIEVES ARE BUSY

Watch your cats. Thieves have been busy in London since the war began stealing them – especially Persians.

An animal welfare authority said yesterday that the thefts appear to be organized. There is a shortage of cat pelts in the fur trade.

A monkey family proud of the sandbag defences in front of the cage at London Zoo. Larger animals had been evacuated to Whipsnade, and after the Zoo reopened on 15 September 1939, its Californian sea lions were sent ‘on loan to the National Zoo Park, Washington, for the duration of the war’.

A month later a Hampstead cleaner had heard the rumour: ‘You know what they’re doing with all them cats what vanishes? They use the skins for lining British Warms [overcoats], and they boil the fat down for margarine or something. They do say there is cats in pies.’

A month before Armistice Day,

Picture Post

published a letter from Mrs Stelfex of Broadoaks Road, Flixton, Manchester: ‘The Cenotaph here is desolate and flowerless. Men hurry by and do not raise their hats. What is going to happen on 11 November this year? To have the usual two minutes silence in honour of those who died in the Great War would be a paradox when lives are still being given in the same cause . . . Yet we can’t just forget our 1914–1918 heroes.’

Picture Post

answered Mrs Stelfex: ‘There will be no service at the Cenotaph this year, in all probability, because crowding together into a public place is forbidden in war-time. Question of silence is still being considered. There is no danger of the men of 1914–1918 being forgotten.’

Officially, there was no two minutes’ silence on Armistice Day 1939 but on the first stroke of 11am, traffic came to a voluntary standstill and passers-by stood bare-headed until two minutes had elapsed. At the Cenotaph, wreaths were laid on behalf of the King and Queen, followed by the chiefs of staff, Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, General Sir Edmund Ironside and Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall on behalf of the fighting forces. Then, a French

matelot

and a Polish staff officer laid wreaths on behalf of Britain’s allies. To mark the anniversary, King George and President Lebrun exchanged telegrams. And in Paris, the Grenadier Guards took part in France’s commemoration of the Armistice at the tomb of the Unknown Warrior at the Arc de Triomphe.

Picture Post

wrote eloquently of the scene in Whitehall: ‘all through day, a crowd of men and women stand around the wreathladen Cenotaph . . . In the grey November light, with their sombre

clothes and gas-mask cases, they look pathetic, almost like ghosts from another age. Some come to lay flowers, some come to look at the wreaths, some come to stand for a moment and think about the men who died – the men whose sons are fighting in a new war now.’

That same day Queen Elizabeth broadcast to the women of Britain and the Empire: ‘War has at all times called for the fortitude of women. Even in other days, when it was an affair of the fighting forces only, wives and mothers at home suffered constant anxiety for their dear ones and too often the misery of bereavement . . . Now this has all changed, for we, no less than men, have real and vital work to do . . . All this, I know, has meant sacrifice, and I would say to those who are feeling the strain: Be assured that in carrying on your home duties and meeting all those worries cheerfully you are giving real service to your country. You are taking your part in keeping the home front, which will have dangers of its own, stable and strong . . .’

C

HAPTER

13

Wartime Entertainment

In Britain, as soon as war was declared, all places of entertainment were closed down. This was done on the orders of the Home Office, ‘until the scale of attack is judged’. This draconian measure prompted a characteristically blistering attack from George Bernard Shaw in

The Times

on

5

September. He described it as a ‘masterstroke of unimaginative stupidity’. He further put forward the novel suggestion that ‘all actors, variety artists, musicians and entertainers of all sorts should be exempted from every form of service except their own all-important professional one’.

While not daring to go that far, on 9 September, the Government did sanction the reopening, until 10pm, of all theatres and cinemas in areas deemed not to be in immediate danger of attack. Two weeks later, permission was given for entertainment venues to open in ‘vulnerable areas’. They too were to shut at 10pm, except in the West End, where a curfew was to operate at 6pm. This proviso lasted until the beginning of December.

At the Victoria Palace, the musical

Me and My Girl

, starring Lupino Lane and Teddie St Denis, was one of the first shows to

reopen. It featured ‘The Lambeth Walk’ and before the war had already chalked up 1,062 performances. The first new musical show opened in October. Entitled

The Little Dog Laughed

, it starred the Crazy Gang and ran for 461 performances; 1,500 troops were invited to the Palladium for the dress rehearsal of the show, which had a cast of eighty, twenty-four tons of scenery, nearly five tons of properties and three tons of costumes. At the show’s start, a topical note was introduced, ‘with a sudden drone of bombers diving on the stalls and a copious shower of pamphlets giving a general low-down on the Nazi leaders’.

Punch

’s critic was highly complimentary: ‘Mr George Black’s aim has been to take the mind of his vast public off the war for a couple of hours, and in this he certainly succeeds . . . what a relief it is to come in out of the dreary black-out to such a scene of cheer and gaiety! It is worth every one of the preceding collisions with a dozen lamp posts and a hundred bulky and detestable strangers.’

The show featured two early wartime hit songs, both sung and later recorded by the Crazy Gang’s Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen. The first was ‘F D R Jones’, written the previous year by Harold Rome for an American political revue

Sing Out the News

. The other was ‘Run, Rabbit, Run’ by Noel Gay, composer of the ‘The Lambeth Walk’. Legend had it that the song referred to the German air raid on the Shetland Islands when ‘Careful inspection of the area involved in the raid revealed the corpse of one rabbit who, there is reason to believe, died as a result of enemy action.’

A month later, the revue

Black Velvet

, starring Churchill’s son-in-law Vic Oliver, opened at the Hippodrome. It too pleased

Punch

’s critic: ‘It makes no notable contribution to the arts, but is very much what is wanted. Gay from the outset, it has a generous number of good turns and is constantly brightened by the personality of Vic Oliver.’ Appearing with the Austrian-born Oliver were Alice Lloyd, ‘who gives an excellent imitation of her ever-to-be-lamented sister Marie’, xylophonist Teddy Brown and Pat Kirkwood, who sang two Cole Porter standards, ‘Most Gentlemen Don’t Like Love’ and ‘My Heart Belongs to Daddy’. The show received the royal seal of approval when the King and Queen and the Dukes and Duchesses of Gloucester and Kent made an informal visit on 27 November.