The Day We Went to War (45 page)

Read The Day We Went to War Online

Authors: Terry Charman

Tags: #History, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Military, #World War II, #Ireland

‘Our number is up, Best.’ Major Richard Stevens

(left)

and Captain Sigismund Payne-Best in captivity. The original German caption claimed that both men were ‘leading agents in the British Secret Service [and were] arrested on the Dutch frontier as they tried to contact the German opposition’.

The three men had last met on 7 November in the Café Backus at Venlo, on the German-Dutch border. There they had agreed that the two British agents would meet with a German general the next day to begin definitive negotiations. That meeting was then put off until the afternoon of the 9th. At 4pm Best and Stevens punctually arrived at the café, only to be kidnapped by a group of SS men under Alfred Naujocks, who had led the bogus attack at Gleiwitz radio station back at the end of August. In the ensuing exchange of fire, Lieutenant Dirk Klop, a Dutch intelligence officer who had accompanied the two British agents at their meetings with Schellenberg, was mortally wounded. Best, Stevens and the dying Klop were thrown, Schellenberg said, ‘like bundles of hay’ into a car, and driven across the border into Germany.

The next day, with rumours of the German attack on Holland in the air, Elsie Warren jotted down in her diary a version of the kidnapping going the rounds: ‘There was an incident on the German-Dutch frontier. A party of Nazis started a shooting affair. Six Dutchmen were kidnapped, one killed. A Dutch car was also taken into Germany. Both Belgium and Holland stand by. They are prepared for any move Hitler might make to invade their land.’

Hitler had indeed intended to invade both countries on 12 November, using as an excuse an entirely bogus French military incursion into Belgium. But on 7 November, he postponed the date of the attack. This was the first of fourteen postponements by Hitler that autumn and winter, the weather usually being given as the reason. But Elsie Warren heard another reason: ‘it is said that German officials refuse to invade Holland’. Moreover, ‘Holland says that although she is prepared for the worst she has no immediate fear of invasion from Germany.’ This view was comfortingly endorsed by

The War Illustrated

: ‘and many a worthy Hollander, listening to the radio and sipping his schnapps, must have wondered what all the pother was about. After all, how many times was Holland on the eve of invasion in the last war?’

A partial explanation of ‘all the pother’ on the Dutch-German border came on 21 November, when Himmler announced that his security service had ‘solved’ the mystery of the Buergerbraukeller assassination attempt. It was done, he proclaimed, at the instigation of the infamous British secret service, two of whose chiefs ‘had been arrested on the Dutch-Frontier’ the day after the bomb attempt. The German press played the story up for all it was worth with photographs of Best and Stevens juxtaposed in the newspapers with one of Elser. Like him, both British agents were incarcerated as privileged prisoners in Sachsenhausen, pending a show trial.

In the meantime, the Café Backus at Venlo had become a focal point for the world press. Geoffrey Cox of the

Daily Express

went to the café to interview the waitress who had witnessed the kidnapping. Cox thought the café very exposed and throughout the interview kept a wary eye on the nearby German border guards. He was left alone, but his colleague Ralph Izzard of the

Daily Mail

had a narrow escape.

Izzard

and a Dutch newspaperman were interviewing the waitress when German troops surrounded the café. Izzard hid in the lavatory, ready to ditch his British passport down the pan should they find him. But the waitress argued with the Germans persuasively that only the Dutch journalist was present, and they left without searching the café.

C

HAPTER

12

The War on the Home Front

As the war entered its third month, elderly spinster Jessie Rex of Hornsey, North London, wrote a letter to young relatives in America. They had written to her asking how Britain at war was faring. ‘We are carrying on as usual,’ she told them, ‘the shops are open in much the usual way . . . occasionally there was a shortage, viz; sugar, but only a temporary affair for a few days.’ But Miss Rex, like everyone in Britain, found the blackout hard to bear: ‘The blackout still needs a bit of getting used to . . . I have been out though, but take a torch . . . I am really nervous of stepping off a kerb without knowing it.’

Mass Observation polls taken during the war’s first months showed that the blackout was the top grievance among both men and women of all ages. A fifty-year-old housewife told an observer: ‘I’ve just barked my shins on a bicycle in the lane. It’s so dark. Old Hitler’s got a lot to answer for.’ While a twenty-five-year-old man told him, ‘This blackout is a bloody nuisance. I wish old Hitler and his gang would drown themselves.’ A sentiment echoed by an anonymous diarist after the failed Munich bomb attempt on Hitler:

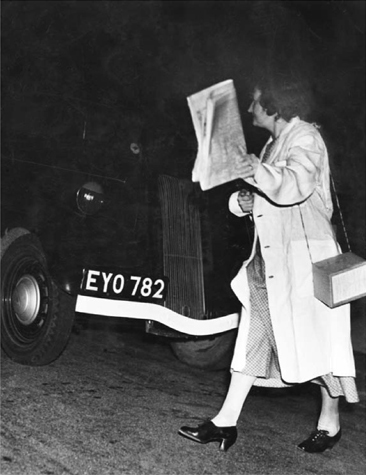

‘I think this black-out’s awful. I haven’t been out in the dark once. I don’t mind saying I’m frightened.’ A South London pedestrian takes precautions when crossing the road in the blackout, 8 September 1939.

‘What a hell of a shame it didn’t get him . . . we should have done our Christmas shopping from lighted windows but for that bastard stepping off the platform twenty minutes too soon.’

Florence Speed in Brixton, on the other hand, thought that ‘the nights are like country nights now, with a velvety darkness which is lovely’. Her own house was ‘draped with black. The fanlight & upper landing windows permanently so, & and the electric bulbs have black shades – very sombre & funereal.’ Her neighbours were much less punctilious about their blackout, as she noted in her diary on 9 September: ‘About mid-night, an ARP warden shouted to the people next door to darken their back windows. There was loud hammering and banging as the curtains were nailed down to the window frames, while the “lady” of the house stood in the garden & bawled instructions. This is their third warning – they are a sleep-shattering family! Only some of them alas! have evacuated.’

Traffic accidents soared in the blackout: 4,133 persons, including 2,657 pedestrians, lost their lives on Britain’s roads during the four months of 1939. The figure for the corresponding period in 1938 had been 2,494. There were many alarmist stories too about the increase of crime in the blackout. The

Daily Telegraph

on 13 November reported the battering-to-death in Stepney of thirty-seven-year-old dock labourer Charles Lawrence: ‘It is possible that police officers passed the body when they went to the assistance of Mrs Emily Murty, a middle-aged women, who was attacked in a street near by and beaten over the head . . .’

In actual fact, crime decreased. In September and October 1939 the Metropolitan Police recorded 12,283 indictable offences. For the same months in 1938, the figure had been 16,023. Only the theft of bicycles had increased. But the fear remained, and a London landlady was heard to say, ‘I’m not going out in all that. At one time I used to enjoy getting the 44 bus to Piccadilly, listening to the band, and coming home at ten. But not now. I’ve never been out after dark since the black-out, and I don’t want to.’

In Blackpool, a forty-year-old insurance manager complained with pent-up frustration, ‘Had a nice night last night. Tommy bloody Handley on the wireless again; read every book in the house. Too dark to walk to the library, bus every forty-five minutes, next one too late for the pictures. “Freedom is in peril,” they’re telling me!’

Morals in the blackout were cause for concern too. A Mass Observer reported, ‘I have heard of two or three cases where young men have boasted of intercourse in a shop doorway on the fringe of passing crowds, screened by another couple who were waiting to perform the same adventure. It has been done in a spirit of daring, but it is described as being perfectly easy and rather thrilling.’

At the Finsbury Park Empire, the flamboyant and risqué musichall comedian Max Miller joked, ‘I bet nobody’ll bump into me in the blackout. Do you like these black nights, ducky, do you like ’em lady? No, no – they’re nice, ain’t they, ducky? I don’t care, I don’t care how dark it is – I don’t care, I like it. All dark and no petrol – I don’t want any petrol. I didn’t ask for any. I don’t. Before the war I used to take ’em out in the country – it’s any doorway now!’

The authorities remained both unrepentant and unresponsive to public grousing over the blackout. Anyone breaking it was liable to be punished. The Lord Mayor, aldermen and citizens of Plymouth were collectively fined £2 for not properly blacking out the city’s Guildhall. Similarly, a Bexley Heath aquarist had to pay a fine of £1 for failing to screen the heating lamp in his fish tank. And a man in Bridgend was fined ten shillings (50p) for striking matches in the street as he tried to look for his false teeth. Mrs Ann Fleming of Renfrew was fined £3 when her six-month-old child had a fit in the middle of the night. In dashing to the child’s room she let a light be exposed for one minute. Mrs Fleming’s appeal went all the way up to Lord Advocate of Scotland before the fine was eventually revoked.

Mr Albert Batchelor was driving his car near Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire, when the radiator burst and washed the black paint off his lamps. For this accidental breach of the regulations, he was fined 15s (75p). At Worthing Police Court in Sussex on Armistice Day, Inspector Wright told magistrates that when he called on ninety-one-year-old Fanny Smith to tell her that she was showing a light, she had replied, ‘I thought it was all over.’ When asked a further question by Wright, Miss Smith told the inspector, ‘I thought the Germans had something better to do.’ She was fined ten shillings (50p).

Some solutions for beating the blackout were quite simple but ingenious, to say the least. Mr A. Collet of Between-Towns Road, Cowley, Oxford told

Picture Post

, ‘We’ve solved the black-out problem, or at least part of it. My pal and I have over a mile’s walk home every night . . . when our first torches ran out, it was a bit of a job, I can tell you. We soon got to know where the lampposts lay, and even the kerb at the crossroads. But it was the people – every few yards we had collisions. Then we got an idea. We started to whistle. Now we have no collisions. People hear us coming and step out the way – and by the time we get home, we’ve quite whistled away those black-out blues.’

Churchill, in a note circulated to his cabinet colleagues on 20 November, suggested that a ‘sensible’ modification of the blackout be made. This was agreed upon, and in time for Christmas, ‘amenity lighting’ was introduced. This was the equivalent to the light of a candle about seventy feet away; 500–1,500 times less bright than the pre-war lights of London.

Those in the civilian army of Air Raid Precautions responsible for enforcing the blackout, especially air-raid wardens with their cry ‘Put that light out!’, soon became targets for the public’s pentup fury and frustration. A thirty-seven-year-old female civil servant told an observer from Mass Observation: ‘I loathe every warden, and would like to murder them.’

‘It’s not very nice to get out of a warm bed and creep down into those things.’ Alan Suter and his sister Doris enter the family Anderson shelter at 44 Edgeworth Road, Eltham, south-east London.