The Dirt (7 page)

Authors: Tommy Lee

I EVENTUALLY FOUND A JOB selling Kirby vacuum cleaners over the telephone, but I couldn’t seem to close a single deal. One of the other salesmen told me about a carpet-cleaning job that was open to anyone with a car. So I took the steam-cleaning job with the sole intention of going to people’s houses and setting up the steamer in front of their bedroom door to keep them away while I raided their medicine cabinets and took all their drugs. For extra money, I’d bring a water bottle with me and tell people that it was Scotchgard, and I could seal their carpets so that the dirt wouldn’t stick. I explained that the going price was $350 for the whole house, but, since I was a student trying to work his way through college, I’d do it for a hundred if they paid me in cash and kept it quiet. So I’d walk around the house spraying water and stealing whatever I thought they wouldn’t notice for a few days.

I was starting to make a lot of money, but I still didn’t pay my rent. The apartment complex was like a skid row version of

Melrose Place

. My neighbors were a young couple, and when they broke up, I started fucking the wife until the husband moved back in. Then I befriended him, and we decided to deal quaaludes because they were in fashion that month. I probably ended up swallowing as many as I sold.

At the same time, I started to put my first band together with Ron and some friends of his: a girl named Rex, who sang and drank like Janis Joplin, and her boyfriend, Blake or something. We called ourselves Rex Blade, and we looked good. We had white pants that laced up the front and back, tight black tank tops, and ratty hair that looked like Leif Garrett on a bad day. We rehearsed in an office building next to where the Mau Maus practiced. Unfortunately, we didn’t sound nearly as good as we looked. In retrospect, the only thing Rex Blade had going for it was that it was a good excuse to take drugs and it earned me the right to tell girls I was in a band.

As usual, my shitty attitude made this period in my life a short one. I think everything I’d experienced was always so short-term and transient that if anything remained stable for too long, I’d panic and self-destruct. So I got thrown out of Rex Blade for making the classic young rock-band mistake that so many others have made before me and will make until the end of time. This happens when you first start writing songs. Your words seem very important and you have your own vision that doesn’t accommodate anyone else’s. You are too narcissistic to realize that the only way to get better is by listening to other people. This problem was compounded by my stubbornness and volatility. If I was Rex or Blake, I would have thrown myself out of that band, too, along with all the little three-chord wonders I thought were such masterpieces.

Days later, the police knocked on my door and threw me out in the street. After a year and a half of not paying rent, I had finally been evicted. I moved into a garage I found in the classifieds for a hundred dollars a month. I slept on the floor with no heater and no furniture. All I had was a stereo and a mirror.

Every morning I’d swallow a handful of crosstops and drive to make the 6

A.M.

to 6

P.M.

shift at a factory in Woodland Hills, where we dipped computer circuit boards in some sort of chemical that could eat your arm off. After working there, playing Pong all day, and fighting with the Mexicans (not unlike the diversions I would later enjoy with my half-Mexican, half-blond lead singer), I’d drive straight to Magnolia Liquor on Burbank Boulevard and work from 7

P.M.

to 2

A.M.

Before leaving, I’d stuff as many bottles of booze as I could fit in my boots and drive an hour to my garage. I’d guzzle the stuff and stand in front of the mirror, fan out my thickening black hair, twist my mouth into a sneer, sling my guitar around my neck, and rock out, trying to look like Johnny Thunders from the New York Dolls until I passed out from exhaustion and alcohol. Then I’d wake up, pop more pills, and start all over again.

It was all part of my plan: I was going to work my ass off until I had enough money to buy the equipment I needed to start a band that would either be insanely successful or attract tons of rich chicks. Either way, I’d be set up so that I’d never have to work again. For extra cash, whenever someone came in to buy liquor, I’d only ring up half the price I charged them. I’d write down the amount I didn’t ring up on a slip of paper and put it in my pants. Then, at the end of the night, I’d total up the money I’d fucked the store out of, pocket it, and close up, eighty bucks the richer. My accounting was never over or under by more than a dollar: I’d learned my lesson at Music Plus.

One night, while I was strung out on speed and alcohol, a slouched-over rocker with black hair walked into Magnolia Liquor. He looked like a creepy version of Johnny Thunders, so I asked him if he played music. He nodded that he did.

“What are you into?” I asked.

“The Paul Butterfield Blues Band and Jeff Beck,” he answered. “What about you?”

I was disappointed that this hunchback, who looked so demented, had such lame, predictable taste. I rattled off the list of the cool music I was into—“The Dolls, Aerosmith, MC5, Nugent, Kiss”—and he just looked at me contemptuously. “Oh,” he said dryly, “I’m into real players.”

“Fuck you, man,” I shot back. Pompous little shit.

“No, fuck you,” he said, not angrily but firmly and confidently, as if I would soon see the error of my ways.

“Get out of my store, asshole.” I pretended like I was going to leap over the counter and kick his Jeff Beck–loving ass.

“If you want to see a real guitar player, come see me tonight. I’m playing down the street.”

“Get the fuck out of here. I’ve got better things to do.”

But of course I went to see him. I may have hated his taste, but I liked his attitude.

That night, I stole a pint of Jack Daniel’s, stuffed it into my sock, and got drunk outside the bar. Inside, I saw that gnarly little leather Quasimodo playing slide guitar with a microphone stand, running it up and down the neck as fast as he could. He was going crazy, beating the shit out of that guitar as if he had just caught it sleeping with his girlfriend. I’d never seen anyone play guitar like that in my life. And he was wasting his talent with a band that looked like abandoned Allman Brothers. After the show, we sat down and got drunk together. I was humbled by his playing and decided I’d forgive him for his shitty taste in music. We talked on the phone a few times afterward, then I lost track of him.

I began moving through bands like crosstops. I’d go to auditions listed in

The Recycler

, join for a day, and then never show up again. I eventually learned to leave my bass in the car trunk when I first walked in to meet a band. If they had no vibe—which was almost always the case since they were all Lynyrd Skynyrd and I was Johnny Thunders—I’d tell them I had to run to the car to get my gear, and then I’d split.

But persistence paid off, and I answered an ad for a band called Garden or Soul Garden or Hanging Garden or Hanging Soul. They were a bunch of shady-looking guys with long black hair, which was more or less what I looked like. However, they played terrible Doors-like psychedelic jamrock, and I split. But I kept running into the band’s guitarist, Lizzie Grey, at the Starwood. He had long curly hair, a tube top, and high heels. A cross between Alice Cooper and a rattlesnake, he was either the most beautiful woman or the ugliest man I’d ever seen, with the sole exception of Tiny Tim. We soon discovered that we both had a passion for Cheap Trick, Slade, the Dolls, old Kiss, and Alice Cooper, especially

Love It to Death

.

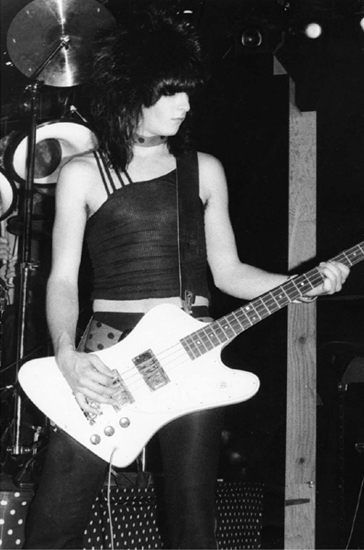

fig. 7

It was through Lizzie that I joined my first band in Hollywood. Lizzie had been invited by a big, intimidating bastard named Blackie Lawless to play in a group called Sister, which also included a raving mad guitarist, Chris Holmes. I knew Blackie from the Rainbow Bar and Grill: He’d just stand in the middle of the room, tall with long black hair, black leather pants, and black eye makeup, and emit some kind of bad-boy magnetic power that would soon have dozens of girls stuck to his side. Somehow Lizzie talked Blackie into letting me play bass in Sister, rounding out a very ugly and menacing band. We practiced on Gower Street in Hollywood, where the Dogs rehearsed.

Blackie was an amazing songwriter and, despite the fact that he was cold and shut-down, he was inspirational to talk to because he was into making an impression not just with music but with appearance. He was into eating worms and drawing pentagrams onstage—anything to get a reaction from the audience. We’d record songs like “Mr. Cool” in the studio, then sit around and talk about how we were going to look onstage or what he was trying to express with his songs for hours. But Blackie fell into the class of people, like me, who saw life as a war—and he always had to be the general. The rest of us were supposed to be good soldiers and nothing more. So Blackie and I soon began butting heads, over and over until we were bruised and bloody and, as band General, he had no choice but to dismiss me from service. He soon kicked Lizzie out as well, and the two of us decided to form our own group.

By that time, I was broke. I had been fired from the liquor store and the factory for blowing off work to rehearse. I found a job at Wherehouse Music on Sunset and Western, where I could get away with showing up whenever I felt like it. When money was really tight, I’d give blood at a clinic on Sunset to pay the bills. One morning while I was taking the bus to Wherehouse Music, I met a girl named Angie Saxon. In general, I had no interest in women except for the moment or two of pleasure they could provide me: The rest of the time they were in the way. But Angie was different: She was a singer, and we could talk about music.

Except for Angie and Lizzie, I had no friends that lasted longer than a week and no one I could trust. Because I was always starving and amped on uppers, I often felt as if I didn’t have a body, like I was just a vibrating mass of nerves. One day, when I was feeling particularly broke and anxious, I decided to find my father. I convinced myself that I was calling him because I needed money—money that he owed me to make up for all the years he had abandoned me—but in retrospect I think I wanted to feel connected to someone, to talk to him and maybe, in the process, learn something about what made me so crazy. I called my grandmother, then my mother, and they told me that last they heard he was working in San Jose, California. I called information, asked for Frank Feranna, and found him. I wrote the number down next to the phone, and downed a fifth of whiskey to work up the courage to dial it.

He picked up on the first ring, and when I told him it was me, his voice turned gruff. “I don’t have a son,” he told me. “I do not have a son. I don’t know who you are.”

“Go fuck yourself,” I yelled into the receiver.

“Don’t ever call here again,” he snapped back, and hung up.

That was the last time I ever heard his voice.

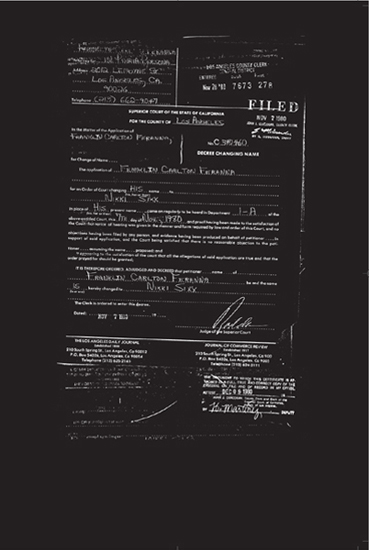

I cried for hours, removing records from their cardboard sleeves and throwing them against the walls, watching them smash to pieces. I grabbed the pieces of vinyl and scraped them up and down my arms, making crisscrosses of raised red flesh punctuated by beads of blood. Though I didn’t think I could sleep that night, I somehow did, waking up in the morning strangely calm with the resolve to change my birth name. I did not want to be saddled for the rest of my life as the namesake of that man. What right did he have to say I was not his son when he had never even been a father to me? First, I killed Frank Feranna Jr. in a song, “On with the Show,” writing, “Frankie died just the other night / Some say it was suicide / But we all know / How the story goes.” Then I made it legal.