The Domesticated Brain (16 page)

Read The Domesticated Brain Online

Authors: Bruce Hood

Tags: #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

It

should be noted that there is not just one gene responsible and there are a multitude of different types of stress that affect individuals differently. In a recent study

50

of teenagers whose parents had reported stress during their child’s upbringing, methylation of environmental stressor genes was investigated. The effects of the mother’s stress were only evident if that stress had occurred when the child was still an infant. Fathers also produced methylation in stress-related genes but only when the child was older, during the preschool years. More intriguing was the finding that this effect was restricted to the girls in the study. It has been reported for some time that absent or deadbeat fathers have a greater influence on their daughters than their sons, but this study is some of the first evidence to point the finger of suspicion at epigenetics.

Warrior genes

On 16 October 2006, Bradley Waldroup sat in his truck drinking heavily and reading the Bible. He was waiting for his estranged wife to arrive with their four kids for the weekend. When his wife, Penny, turned up with her friend Leslie Bradshaw, a fight broke out and Waldroup went berserk. He shot the friend eight times and then chased after his wife before hacking her to death with a machete. It was one of the worst, most bloody crime scenes that Tennessee police officers had ever dealt with. What makes this horrific crime stand out, apart from its sheer brutality, was that it was one of the first cases where defence lawyers successfully argued that Waldroup should not be given the ultimate punishment

of the death sentence because of his genetic make-up. They argued that Bradley Waldroup had a biological disposition towards extreme violence because he carried a

warrior gene

.

This gene was discovered in the Netherlands in 1993 by a geneticist, Hans Brunner, who had been approached by a group of Dutch women who were concerned that the males in their family were prone to violent outbursts and criminal activity including arson, attempted rape and murder.

51

They wanted to know if there was some biological explanation. Brunner soon found that they all possessed a variant of the monoamine oxidase A, or

MAOA

gene located on the X chromosome. In the following years, evidence mounted to support the link between patterns of aggression and low-activity MAOA. The condition would have remained known as the rather lame ‘Brunner Syndrome’ if it had not been for the columnist Ann Gibbons, who christened it the ‘warrior gene’.

52

The emotive name is a bit of a misnomer as it is more of a

lazy

gene because it fails to do its main job, which is to break down the activity of neurotransmitters.

With the discovery of the warrior gene, soon everyone was looking for this biological marker in the underclass of society. Male gang members were more likely to have the warrior gene and four times more likely to carry knives. In one particularly inflammatory report

53

based on a very small sample of males, New Zealand’s indigenous Maoris, famous for their warrior past, were found to have the gene. Not surprisingly, this report created a public outcry.

One of the problems with these sorts of studies is that they relied on self-report questionnaires, which are often inaccurate. One ingenious study

54

tested the link between

the warrior gene and aggressive behaviour by getting males to play an online game where they could dish out punishment in the form of administering chilli sauce to the other anonymous player. In fact, they were playing against a computer that was rigged to deliver a win to itself despite the best efforts of the male participants. Those with the low-activity MAOA gene wanted revenge and were significantly more likely to deal out punishments in retribution.

The warrior gene may be linked to aggressive behaviour, but as Ed Yong, the science writer, puts it, ‘The MAOA gene can certainly influence our behaviour, but it is no puppet-master.’

55

One of the main difficulties in explaining violent behaviour like that of Bradley Waldroup is that around one in three individuals of European descent carry this gene, but the murder rate in this population is far less. Why don’t the rest of us with the gene go on a bloody rampage?

The answer could come from epigenetics. Genes operate in environments. Individuals are more likely to develop antisocial problems if they carry the low-activity MAOA-L

and

were abused as children. Researchers studied over 440 New Zealand males with the low-activity MAOA gene and discovered that over eight out of ten males who had the deficit gene went on to develop antisocial behaviours, but only if they had been raised in an environment where they were maltreated as children.

56

Only two out of ten males with the same abnormality developed antisocial adult behaviour if they had been raised in an environment with little maltreatment. This explains why not all victims of maltreatment go

on to victimize others. It is the environment that appears to play a crucial role in triggering whether these individuals become antisocial.

As for Bradley Waldroup, was it right for him to be treated more leniently? He certainly had an abusive childhood, but probably no greater than other males in that trailer park in a socially deprived area of Tennessee. A third of them presumably also carried the gene. At the time, Waldroup was drunk and we know that alcohol impairs our capacity to regulate rage and anger arising from the limbic system. But was he accountable for his actions?

What is clear is that it was the evidence for a warrior gene that persuaded members of the jury to find Waldroup not guilty of murder even though it is clear that they did not fully understand the nature of gene-environment interactions. After the Waldroup outcome, one might think that raising the presence of the warrior gene and abusive childhood would make for a good defence strategy in the law courts. However, there is another way of seeing the argument. One could argue that those with a genetic predisposition towards violent crime should not be let off more lightly but rather punished more severely. This is because they are more likely to reoffend and so the deterrent should be even harsher. Warrior genes and abusive childhoods are risk factors that make some more inclined to violence, but then again, punishment and retribution are also factors that reduce the likelihood of committing crimes. The decisions we make throughout our life represent the interaction of biology, environment and random events. Deciding which is

more important is the job of society operating through its laws and policies, but it would be wrong to think that the answer is simple.

The landscape of life

It is a cliché but we often talk about life as a journey with many forks and turnings. Just think about where you are today and how you got here. Did you know ten years ago where you would be today? Although some things in life are certain (death and taxes) and some are likely, many events are unpredictable. And some leave a lasting impression.

As we develop from a simple ball of cells into an animal made up of trillions of cells, the process is guided by instructions shaped by natural selection over the course of evolution and encoded in our genes. However, the genome is not a blueprint for the final body but rather a script that can vary depending on events that take place during development. These are not only events outside the womb, but also those within the unfolding sequence of body building, which explains why identical twins end up different despite sharing the same genes. They may start out with the same genome, but random events can set them off on different pathways as the body is being constructed. This explains why there are increasing differences observed in genetic methylation for identical twins the older they become. Even cloned fruit flies raised in the same lab-controlled environment should be absolutely identical and yet have different arrangements in their brains. When you consider the complexity of neural networks and the

explosion of synapses with googols of connections, it seems obvious that no two brains could ever be the same.

Despite the diversity in brains that is inevitable during development, evolution still produces offspring that resemble their parents more than they resemble another species. The majority of genetic information must be conserved and yet remain flexible enough to allow for individual variation arising from events that occur during the developmental process. One way to consider the influence of genes and environment is to think about the journey through life as an epigenetic landscape.

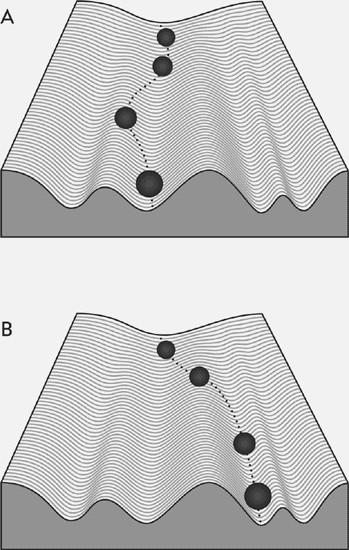

In 1940, the brilliant British polymath Conrad Waddington used a metaphor of a ball rolling down a corralled landscape made of up troughs and valleys of different depth. The diagrams overleaf represent two paths of development in two individuals (A and B) who have the same starting genotype, as in the case of identical twins. These two individuals therefore inherit the same probability of developing a certain phenotype – the expression of those genes into characteristics that emerge over one’s lifetime. However, they may have different actual phenotypic end points, determined by chance events and environmental effects, especially at critical points. At each junction, development can take a different path but whether it stays on course depends on the depth of the gully. Some gullies or canals are very deep, so the ball has no option but to follow that trajectory and it would take a mighty upheaval to set it on another course. These are the genetic pathways that produce very little variation in the species. Other canals are shallower, so that the path of the ball could be more easily set on another route by a slight perturbation. These are aspects of development that may have a genetic component but outcomes can be easily shifted by environmental events.

Figure 7: Waddington’s epigenetic landscape

(After Kevin Mitchell, PL.S Bristol © 2007)

Waddington’s

metaphor of canalization helps us to think about development as a probabilistic rather than deterministic process. Most of us end up with two arms and two legs but it is not inevitable. Something dramatic during foetal development could produce a child with missing limbs, as happened during the 1960s when the drug thalidomide was given to pregnant women to prevent morning sickness. Other individual differences are much more susceptible to the random events in life that can set us off on a different course. This can happen at every level, from a chance encounter with a virus as a child to growing up in an abusive household.

Unravelling the complexity of human development is a daunting task and it is unlikely that scientists will ever be able to do so for even one individual, because the interactions of biology and environment are likelihoods and not certainties. There are just too many ways that the cards could stack up. More importantly, as the vernacular saying goes, ‘Shit happens’, which is a very succinct and scientifically accurate way of saying that random events during development can change the course of who we become in unpredictable ways.

One

day a scorpion and a frog met on a riverbank. The scorpion asked the frog to carry him across the water on his back because he could not swim. ‘Hold on,’ said the frog, ‘How do I know that you won’t sting me?’ ‘Are you insane?’ the scorpion replied. ‘If I sting you, then we will both die.’ The frog, reassured by this, agreed to carry the scorpion on his back across the river. Halfway across, the frog felt the sharp, fatal puncture from the scorpion’s tail. ‘Why did you do that? Now we are both doomed,’ cried the frog, overcome by venom, as they both began to sink below the water. To which the scorpion replied, ‘I can’t help it. It’s in my nature.’

The story of the scorpion and the frog has been retold for thousands of years. It is a tale about urges and impulses that hijack our behaviours despite what is often in our best interests. We like to believe that we are in control and yet our biology sometimes gets in the way of what is best for us. As animals with the capacity to reason, we think that we are capable of making informed decisions as we navigate the complexity of life. However, many of the decisions we make are actually controlled by processes that we are not always aware of or, if conscious, seem beyond our volition.