The Dragonfly Pool (13 page)

Read The Dragonfly Pool Online

Authors: Eva Ibbotson

These were the things that matteredânot her own wishes and hopes and needs.

But it didn't work. Tears welled up under her eyelids and she felt completely desolate.

From the moment she had seen those images of Bergania, she had felt as though the country somehow spoke to her. And now though her friends would go, she would stay behind.

“You realize that all the parents have to pay thirty pounds for our fares,” Verity had said. “The school can't afford them. Daley's going to write a letter to everyone and explain.”

Verity always knew things before other people.

Thirty pounds. It was nothing to Verity's parents, with their estate in Rutland, and most of the others came from well-to-do families. But Tally would never ask her father for so much money. His patients were poor; he had both the aunts to support. He mustn't be asked in case he felt he had to make the sacrifice and, whatever Tally wanted from her father, it was not a sacrifice.

“It doesn't matter,” she told herself.

But it was no good. Perhaps it didn't matter compared to people dying in famines and earthquakes and wars, but it mattered to her.

After a while she got up and brushed the grass off her skirt and made her way back up the hill to school.

She would see if Matteo was free.

She found him in his room, looking down a microscope on the windowsill, but when he saw her tearstained face he pulled out a chair for her at the wooden table.

“I see you have a problem,” he said. “A proper one, for yourself.”

“Yes, I do.” She felt better now that she was taking some action. “It's . . . I want you to tell the headmaster not to write to my father about the fare to Bergania. Verity says it's thirty poundsâthat's right, isn't it?”

“It sounds about right. Why?”

“Well, I know my father can't afford it, and I don't want Daley to ask him in case he . . . I don't want him to be asked. I don't have to go. I can show one of the others how to take my place.”

“I see. But you want to go, don't you?”

Tally wiped her eyes with her sleeve. “Yes, I do. I wanted to go from the minute I saw the travelogue about Bergania. Butâ”

“Why?”

Matteo had spoken sharply. Tally blinked at him. “I don't know really. It's very beautiful . . . the mountains and the river . . . And the procession. Usually processions are boring, but the king . . .”

“Yes?” Matteo prompted her. “What about the king?”

“He looked so strong and . . . braveâexcept I know you can't really look brave just for a moment in a film. Only he did. But tired, too. And there was the prince . . . he was hidden by plumes . . . feathers all over his helmet. I was sorry for him.” She shook her head. “I don't know . . . there was a big bird flying above the cathedral.”

“A black kite, probably,” said Matteo. “They're common in that part of the world.” But he seemed to be thinking about something else. Then: “I'll speak to the headmaster.”

“You'll tell him not to write to my father about the money?”

“Yes, I'll tell him that.”

As Matteo knocked on the door of Daley's study, four children came outâJulia and Barney and Borro and Tod.

“You've had a deputation, I see,” said Matteo. “Not connected with the trip to Bergania?”

“Yes,” said the headmaster. “They want the school to pay for Tally's fare to Berganiaâthey don't think her father could afford it. I must say that girl has made some very good friends in the short time she has been with us.”

“And will the school pay it?”

Daley looked worried. “The trouble is if you do that kind of thing once you have to do it again, and we simply don't have funds for that.”

“So it would have to come out of the Travel Fund. The fund that exists for worthy cultural exchanges to broaden the minds of the young and all that.”

Daley looked at him blankly. “There isn't such a fund.”

“There is now,” said Matteo. “I shall pay in thirty pounds this afternoon.” And as the headmaster continued to stare at him he said, “Don't worry, I have the moneyâafter all, I got paid last month. Who are you sending with them?”

“I thought Magda should goâher German is fluent, of course, and she also speaks Italian and French. But one will need somebody who can actually cook because they'll be camping some of the time, and I can't send ClemmyâI shall need her here to look after the children left behind in Magda's house. And I'll want a man as well. O'Hanrahan is rehearsing a play for the younger ones and the professor is too old. I thought maybe David Prosser.” The headmaster sighed. “It has to be someone who can be spared.”

Matteo nodded. Prosser could certainly be spared. He was famous for being the most boring man in the school, and for being in love with Clemencyâbut for not much else. There was a pause. Then: “I can cook,” said Matteo.

“Good God!” said Daley, staring at him. “Don't tell me you meant to go yourself all along?”

“Only if the children had been serious. Only if they really meant to work. Not just Tally, all of them.”

“And if they hadn't been?”

Matteo shrugged. “Who knows?” he said.

Part Two

CHAPTER ELEVEN

The Prince Awakes

I

t was a very large bedâa four-poster draped in the colors of

t was a very large bedâa four-poster draped in the colors of

Berganiaâred, green, and white. Green was for the fir trees that hugged Bergania's mountains, red for the glowing sunsets behind the peaks, white for the everlasting snows. On the head-board were carved a crown and the words THE TRUTH SHALL SET THEE FREE, which was the country's motto.

The bed was too large for the boy who now woke in itâbut then everything in the palace was too large for him. His bedroom could have housed a railway carriage; in his bathtub one could have washed a company of soldiers. Even his name was longer than he needed it to be: Karil Alexander Ivo Donatien, Duke of Eschacht, Margrave of Munzen, Crown Prince of Bergania.

He was twelve years old and small for his age, with brown eyes and brown hair and an expression one does not often see in the portraits of princes: the look of someone still searching for where he belongs.

Now he stretched and sat up in bed and thought about the day that faced him, which was no different from other days. Lessons in the morning, inspecting something or opening something with his father in the afternoon, then more lessons or homework . . . and always surrounded by tutors and courtiers and governesses.

For a moment he looked out at the mountains outside the windows. On one peak, the Quartz Needle, the snow never melted entirely, even now in early summer. He imagined getting up and escaping and walking alone up and up through the fir woods, across the meadows where there were marmots and eagles . . . and up, up till he reached the everlasting snow and could stand there, alone in the cold clear air.

There was a tap on the door and a footman entered with his fruit juice and two rusks on a silver tray. Not one rusk, not three, always two. After him came the majordomo with the timetable for the day, and then another servant to lay out his clothes: his jodhpurs and riding jacket, his fencing things, and the uniform of the Munzen Guards which Karil particularly hated. The stand-up collar rubbed his neck, the white trousers had to be kept spotless, and the plumes on the helmet got in his eyes.

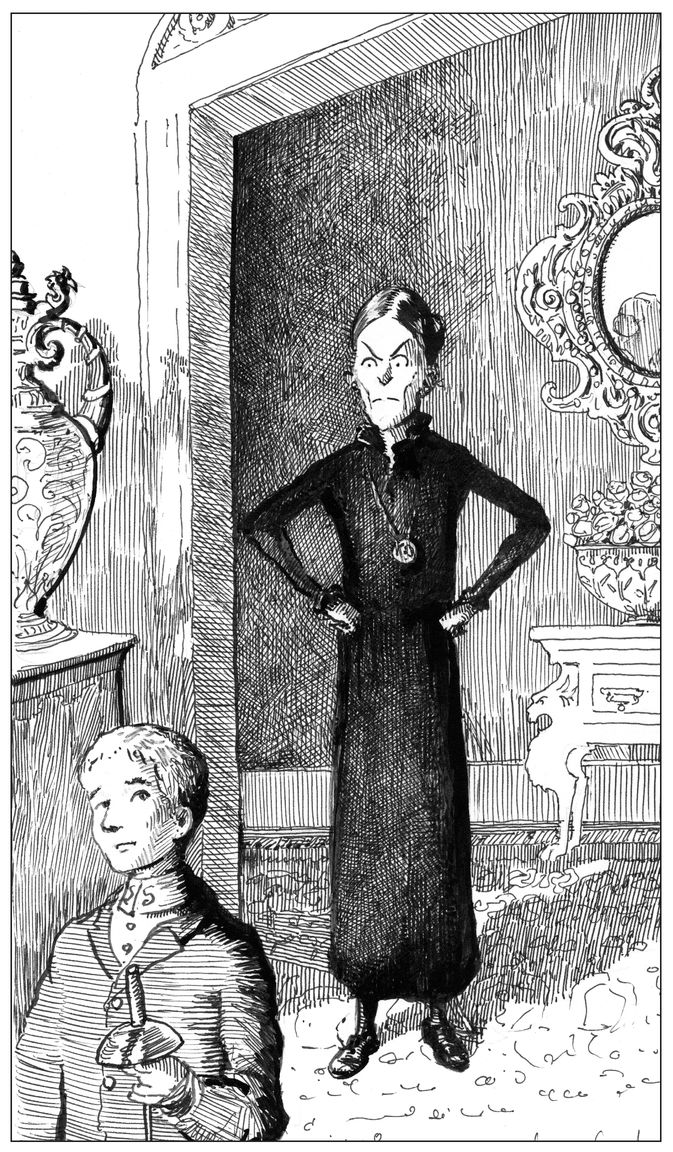

And now came the woman who would scold him and hover over him and criticize him all day. Frederica, Countess of Aveling, was tall and bony and dressed entirely in black, because someone in the Royal Houses of Europe had always died. She was in fact a human being, but she might as easily have been a gargoyle that had stepped down from the roof of a dark cathedral. Her ferocious nose, her grim mouth, and jagged chin looked as though they could well be carved in stone.

Officially she was the First Lady of the Household, but she was also the prince's second cousin and had come over from England after the death of the prince's mother in a riding accident when he was four years old.

Queen Alice of Bergania had been Britishâthe daughter of the proud and snobbish Duke of Rottingdene, who lived in London, in a large gray mansion not far from Buckingham Palace. Although English was the second language of the Berganian court, the duke did not trust foreigners to supervise the education and behavior of his grandson and had sent the fiercest of his unmarried relatives to see that the boy behaved correctly and with dignity at all timesâand never forgot exactly who he was.

In the palace, and to Karil himself, she was known as the Scold, because scolding was all she seemed to do.

“Good morning, Your Highness,” she said, and curtsied. She always curtsied when she greeted him in the morning, and from the depth of her curtsy Karil could tell how badly she was going to scold him. The more displeased she was, the deeper did she sink toward the ground. This morning she practically sat down on the floor, and sure enough she began to scold him straightaway.

“I really must speak to you about the way you have been waving to children when you are out driving. Of course, to extend your arm slightly and bring it back again is right and proper. It is expected. But the way you greeted those children outside their school yesterday was quite inexcusable, leaning out of the window. You cannot expect your subjects to keep their distance if you encourage them like that.” She broke off. “Are you listening to me, Karil?”

“Yes, Cousin Frederica.”

“And when will you realize that servants are not to be addressed directly except to give orders to? I heard you yesterday asking one of the footmen about his daughter in a way that was positively chatty.”

“She was ill,” said Karil. “I wanted to know how she was getting on.”

“You could have sent a message,” said the Scold. She moved over to the chair on which the valet had laid out the prince's uniform, picked up the helmet and peered at it suspiciously. There had been a most shocking incident once when Karil had cut the plumes off the helmet of the Berganian Rifles just before an important parade.

“I haven't done anything to it,” said Karil. “It was only once, because I wanted to be able to see.”

“I should hope not. Cutting the ends off valuable ostrich feathers! I've never heard of anything so outrageous. However . . .” the Scold's face changed and took on a coy and simpering look, “I have something here that will please you. A letter from your cousin Carlotta. It encloses a photograph which I will have framed so that you can have it in your room.”

She handed Karil a letter which he put down on a gilt-legged table.

“Well, aren't you going to read it?”

“Yes, I willâlater. I want to go outside for a moment before breakfast.”

“I'm afraid that won't be possible.” She consulted a large watch on a chain which she wore pinned to her blouse. “We are already four minutes late.”

Karil sighed and took out the photograph. Carlotta von Carinstein was a year younger than the prince and very pretty, with ringlets down to her shoulders. She was wearing a floating kind of dress with puffed sleeves and holding a bunch of flowers, and she was smiling. Carlotta always smiled.

He already had three of her photographs.

The countess controlled her irritation. It was obvious that Carlotta and Karil would marry in due course and it was time that the boy realized this. Carlotta lived in London with Karil's grandfather, the Duke of Rottingdene. Of course, both the prince and Carlotta were very young but it was sensible in royal households to have these things understood from the beginning.

“Now, Karil,” she said, “here is the program for the day: math and French with Herr Friedrich as usual, then history and Greek with Monsieur Dalrose. At luncheon you will sit next to the Turkish ambassador's wifeâshe has asked to meet you because she has a son your age, and you will talk to her in French. Your fencing lesson with Count Festing is at the usual time, but your riding lesson has been put forward to allow you to change for the inspection of the new railway station at which you will accompany your father.”

“Are we riding or driving?”

“You are driving. Your father will be in the Lagonda; you go in the next car with the Baron and Baroness Gambetti.”

Karil tried to hide his disappointment. He saw his father so seldomârarely before dinner and often not then. Days passed when he did not see him at all. Even though he was not allowed to chat in the royal car, it was good to be beside him. His father was a stern and conscientious ruler, and he seemed to care for nothing except his work. Sometimes Karil felt that his father had really turned into that bewhiskered, solemn personâKing Johannes III of Berganiaâwhose pictures hung in the schools and public places of his country.

Other books

Daisy and the Trouble with Zoos by Kes Gray

Adam and Evelyn by Ingo Schulze

In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust

Rough Trade by edited by Todd Gregory

Sargasso of Space (Solar Queen Series) by Norton, Andre

The Glass Rainbow: A Dave Robicheaux Novel by James Lee Burke

Shard Knight (Echoes Across Time Book 1) by Ballard, Matthew

The Right and the Real by Joelle Anthony

Fall Apart by SE Culpepper

Rani’s Sea Spell by Gwyneth Rees