The Dulcimer Boy

Authors: Tor Seidler

Tor Seidler

Illustrations by Brian Selznick

For Karen Russo

âT.S.

For Tamar Brazis

âB.S.

THERE WAS A STRANGER at the front door with aâ¦

THE TWO LITTLE BOYS were installed in the bedroom nextâ¦

A FINE LINDEN TREE stood in the yard of theâ¦

WILLIAM MADE REMARKABLE progress on the dulcimer. He found heâ¦

A DROP OF COLD WATER landed on his cheek, andâ¦

HE WOKE IN A hammock. It was strung up inâ¦

THE NEXT MORNING, William awoke from a wonderful dream inâ¦

THE GLASS RAISED a bump like a quail's egg onâ¦

UNTIL ALMOST ONE in the morning Drake listened to theâ¦

THE SEAMAN HEARD the same noise overhead but paid itâ¦

WILLIAM OPENED HIS EYES and realized he was having hisâ¦

IT WAS A LARGE one-room shack with an oilcloth windowâ¦

THE CANDLE FLAME began to dance. The draft grew stronger,â¦

A FEW MINUTES LATER the old gentleman led William andâ¦

Â

William has the brown hair and Jules the gold

But without another word the stranger took himself off

T

HERE WAS A STRANGER

at the front door with a wicker chest under his arm.

“Tradespeople use the back,” said the massive, bald-headed gentleman who answered.

Instead of turning away, the stranger handed him a card.

“This be you?” he asked.

The bald gentleman took the card. It read:

EUSTACE CARBUNCLE, ESQ

.

THE CARBUNCLE ESTATE

THE HILL ABOVE RIGGLEMORE

NEW ENGLAND

Mr. Carbuncle nodded curtly but did not ask the stranger in. The stranger's curly brown hair was full of dust, and his navy-blue clothes were scruffy. He also stammered in an undignified manner: the words jerked out of his mouth as if they would have preferred staying inside him.

“This here'sâ¦for you then. Used to belong to your wife's sister, but your wife's sisterâ¦she died. A weakly creature she was, and she'sâ¦gone away.”

“Ah,” Mr. Carbuncle said, removing his hands from the pockets of his smoking jacket to accept the wicker chest. “And she remembered us in her will? Something of value, perhaps?”

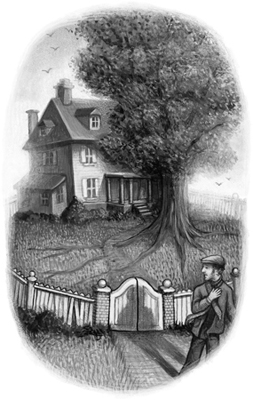

But without another word the stranger took himself off, hurrying through the gate in the picket fence and down the hill.

In Mr. Carbuncle's mouth was a thick black cigar, which rescued his large pink face from suggesting a certain harmlessness. The cigar

twitched at the fellow's behavior. But in a moment he turned and took the wicker chest into the house.

“Amelia, my dear,” he called out. “Something from your sister.”

Mrs. Carbuncle entered the hall with a weary sigh and a faint odor of disinfectant. She was a narrow, black-stockinged woman with her hair caught up in a black scarf; her narrowness and hardness of feature were in strong contrast to her husband. She leaned her broom against the banister and came over to the hall table, where he had deposited the chest.

“My sister?” she said. “But I haven't seen her these years. Why would she send us something now, out of the clear blue sky?”

“She died,” Mr. Carbuncle replied. “You never knowâit might be something of value.”

“Oh, well then,” said Mrs. Carbuncle.

They opened the lid to the wicker chest.

Inside were a tiny boy with golden curls, an equally tiny boy with hair all different shades of brown like a bowl of nuts, and a strange musical instrument. The boys were both sound asleep, and a note was wound in the instrument's silver strings. It said:

William has the brown hair and Jules the gold.

They are ten months old.

This dulcimer is all their father has to give them.

Mrs. Carbuncle crossly tore the note into little pieces. She was careful, however, to stuff the pieces into her apron pocket, letting none of them drop on the floor, for she had already done the hall that morning.

“Who even knew Molly was married?” she cried. “A wonderful wedding announcement!”

She then went to the hall closet and began to pull on a pair of galoshes. When Mr. Carbuncle

asked her why, she explained, “You know how it is down there around the orphanageâall that river muck.”

Mr. Carbuncle looked from his wife to the strange merchandise in the wicker chest. Beside the chest stood a pewter bowl full of unpaid bills.

“Let's not be rash, Amelia, my dear,” he said, puffing thoughtfully on his cigar.

“Mr. Carbuncle?”

“It occurs to me that we've been handed a golden opportunity.”

“Golden opportunity?”

“Mmm.”

Mrs. Carbuncle stared aghast at the gentleman of leisure she had married.

“But, Mr. Carbuncle! You can't be thinking of taking them in! Think of the expense, sir! Think of the wear and tear on your furniture, your rugs. And we can't even afford to reshingle the roof!”

“Exactly,” said Mr. Carbuncle, lifting his eyes in that direction. “Don't think the neighbors haven't noticed.”

He could not see through to the roof that was in disrepair, but he could see the ceiling moldings, around which his cigar smoke was curling. They were very grand, but they were dingy in spite of all his wife's efforts. “Besides,” he added, “these two won't eat much.”

Mrs. Carbuncle's face grew very pinched, but she did not drop her tone of servility.

“I don't understand, Mr. Carbuncle,” she said.

“Two objects of charity, Amelia. Don't you see? Two objects of charity under our roof. That's better than painting

and

shingling!”

All Mrs. Carbuncle could do was sigh.

“Oh, well then,” she said.

T

HE TWO LITTLE BOYS

were installed in the bedroom next to that of the Carbuncles' son, Morris. On Sunday the family went for a stroll down into Rigglemore, pushing the two boys ahead of them in a pram. It quickly became known that they had taken two objects of charity under their roof.

That evening, as every evening, Morris excused himself from dinner the instant he had finished his second dessert and took himself off to bed. He believed he grew faster lying down, fooling the pull of gravity. Although he was not yet as tall or as meaty as his father, it

was his great ambition to outstrip him.

Mrs. Carbuncle served her husband his usual coffee and brandy and struck the match for his after-dinner cigar. But he neither sipped nor puffed with his usual relish.

“People seemed impressed, didn't you think?” she said, puzzled.

Mr. Carbuncle frowned, turning to William and Jules, who were squeezed into a high chair on his left.

“How old was Morris when he started to talk?” he asked.

“Why, he said âpotato' at fourteen months,” she replied.

“But they're only ten months. And that one already babbles like a brook.”

He pointed his cigar at William, the one with the nut-brown hair, who in fact had looked from side to side throughout the afternoon stroll, saying, “Dog.” “Yellow.” “Old man.”

“Well,” said Mrs. Carbuncle, “some children are slower than others. It doesn't meanâ”

“For Heaven's sake! Morris isn't âsome child.' He's a Carbuncle!”

Turning his great, dinner-flushed face on Jules, the one with golden hair, who was nearer him in the high chair, Mr. Carbuncle said, “You don't talk yet, do you?”

Jules, who had not spoken that day, opened his mouth, closed it, then opened it again. A small, rather unintelligible sound came out. Mr. Carbuncle, having just taken a puff on his cigar, exhaled. As the thick smoke enveloped Jules's little face, his mouth closed, his blue eyes blinked in surprise.

“Black,” William commented, pointing to the cloud of smoke.

The ceremony of asking Jules if he could talk and then blowing cigar smoke in his face became as regular as Mr. Carbuncle's after-dinner

brandy. Eventually Jules stopped opening his mouth. And as he grew older, he never made a sound, at the dinner table or away from it.

William, on the other hand, became glibber and glibber. After a few months he began to imitate Morris.

“May I have the end piece, please?” William would say. “And gravy on everything?”

Once, however, he imitated Morris too closely.

“May I have more hollandaise, Pa?” he said, handing back his plate.

On this occasion Mr. Carbuncle's face, hovering over the steaming dish of asparagus, darkened dangerously. Horrified, Mrs. Carbuncle corrected William's presumption.

Since Jules never answered when asked what he cared for, he was given slender, often meatless servings. As time went by, William found himself with less and less appetite for the meat

his brother went without, and eventually he began to refuse meat himself.

They hardly grew at all. Mr. Carbuncle, being a gentleman of leisure, spent most of his time at home, and as the years passed, the sight of two such puny things became positively offensive to him. Finally Mrs. Carbuncle moved them from their bedroom up to the attic, where they would be more out of sight.

At the dinner table Mr. Carbuncle would shake his head sadly, noting the number of cushions they required on their chairs in order to reach the table.

“And one of them dumb as a post to boot,” he would sigh. “What did we do to deserve it, Amelia?”

But she had far too much respect for her husband ever to remind him that he had once referred to them as a golden opportunity.

Â

One day, when the boys were six, Mr. Carbuncle remarked, “I suppose the runts could start school.”

On Monday morning he led them down the hill to the school on Elm Street where Morris went. But when it came to adding the boys' names to the roll in the principal's office, Mr. Carbuncle balked. The name of their father, the man his wife's sister had married, was a mystery to him.

The idea of enrolling boys without surnames made the principal cluck his tongue. He suggested “Carbuncle.” Mr. Carbuncle handed him back his pen indignantly, nib first, and led his two charges away.

So William and Jules continued to stay home all day and learned to read and write only by looking into Morris's books while Morris was resting up. The boys were deeply distressing to Mrs. Carbuncle. She had a great fervor for

cleaning: her attitude toward the floors and furniture, especially the Carbuncle antiques, was religious. Unlike Morris, the two boys would sometimes move around the house, going from one room to another. Often they left fingerprints on the arms of chairs or on banisters or doorknobs.

Sometimes they would even chance to leave a print on one of the Carbuncle antiques, making Mrs. Carbuncle quite wild. Although she never raised her voice to her husband, she could hit piercing notes, and she got into the habit of chasing the boys upstairs with a broom, screaming that she wished they were both stuffed and hung up on a wall.

This was hard on Jules. Although he could not speak, his ears were extremely sensitive. To escape the piercing notes, he would scramble up the stairs and up the ladder into the attic, where he would huddle in a corner under the slant of

the roof, his hands clapped over his ears.

On one of the top shelves was a musical instrument

William, on the other hand, rarely bothered to go farther than to hide by the antique mahogany secretary that stood on the landing at the top of the stairs. Mrs. Carbuncle's moods were well known to him by this time; in a minute she might turn around and send him on an errand to the grocer's. But even when her voice had died down, like a crow flying off into the distance, William would remain by the antique secretary, coming out and staring up at it. The pediment resembled two waves about to break, and on one of the top shelves was a musical instrument, strange and lovely behind the glass doors, like something underwater.